For more than 25 years, the English-language newspapers in Cambodia have had the freedom to print the news as they saw fit, exposing corruption, writing about patronage, telling stories about deforestation, forced evictions and fraud.

The freedom, which eclipsed that seen in the Khmer-language press, had political roots, said journalist Sebastian Strangio, who relocated to Phnom Penh for a reporting job in 2008.

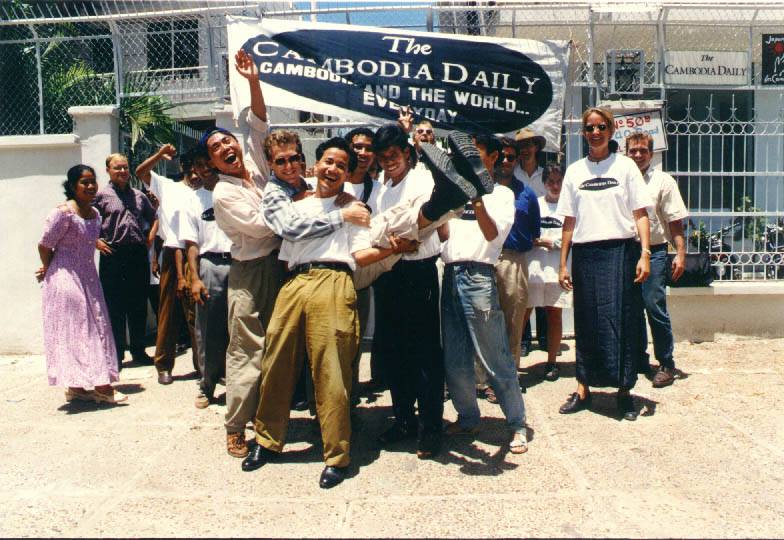

It came as part of the “diverse civic forces” unleashed in the early 1990s by the U.N. Transitional Authority in Cambodia, the peacekeeping operation that controlled Cambodia between 1992 and 1993, Mr. Strangio said.

Those beginnings led him to harbor suspicions that the foundations of the likes of The Cambodia Daily and its crosstown rival, the Phnom Penh Post, where Mr. Strangio worked, were shakier than appeared on the surface.

“There was also a sense that the freedom our papers enjoyed—a freedom unique in Southeast Asia—was the result of an international settlement that wasn’t guaranteed to last,” said Mr. Strangio, who went on to write “Hun Sen’s Cambodia.”

Earlier this month, those suspicions became a reality for the Daily as it was slapped with a $6.3 million tax bill and ordered by Prime Minister Hun Sen to pay by September 4 or “pack up and go.” Analysts have branded the fast-tracked threat as an attempt to silence the Daily’s often-critical coverage and curb independent media, while the paper’s owner has disputed the hefty sum and requested a full audit. Douglas Gillison, who reported and served as executive editor of the Daily between 2005 and 2011, said he felt a free English-language press had been a necessary concession in order to end its international isolation after the Vietnamese withdrew from the country in 1989.

That, along with the fact the Daily had little circulation among the voting public in the provinces, meant the ruling party grudgingly accepted a critical foreign press.

“Though relations were volatile, the CPP apparently believed that it more or less had to accept this in exchange for returning to the embrace of the so-called international community,” Mr. Gillison said in an email. “Furthermore, we were interesting.”

Journalists were aware they were sometimes treading on thin ice, with few legal protections if they found themselves under pressure from authorities.

“I came from New York newspapers, where I’d always dealt with in-house lawyers who could clear sensitive copy for publication and defend us in court. But at The Daily, it was clear there was no point keeping someone like that on staff,” Mr. Gillison said.

“If we got sued, it would be resolved through a balance of competing powers, with the law often verging on irrelevance. No one could give a professional legal opinion pre-publication because the courts would just act at the behest of executive power anyway,” he said.

“Instead, it was down to editors, often alone, to determine what was true, legal, important and fair. Printing anything less would undermine The Daily’s mission. And if they still came after us, at least we could stand by our work,” he added.

In 2009, Mr. Gillison wrote a series of highly sensitive stories about a 1997 grenade attack on an opposition rally based on declassified FBI documents. He said the editors had “no idea” how the government would react.

“We just put tomorrow’s paper to bed and hoped for the best,” he said.

Why now?

Mr. Strangio said that the recent government legal pursuit—which included banning the U.S.-based democracy-building NGO National Democratic Institute on Wednesday and ordering its staff to leave the country within a week—had been a long time coming.

“For Hun Sen and his colleagues, the end of the Cold War and the signing of the Paris Agreements in 1991 was not the start of a great new era of democracy and hope, as many saw it in the West, but rather an extension into a new arena of the political battles of the preceding 12 years,” he added. “These senior officials have long memories.”

Asked what had changed, Mr. Strangio was unequivocal.

“In one word: China,” he said.

While the government was once required to walk a tightrope in appeasing Western donors, the growing financial backing from China—and its lack of demands in promoting democracy, human rights and freedom of expression—has resulted in the government seeing no reason to even pay lip service to such ideals.

“Now, strong backing from Beijing has made the CPP government less dependent on the support of Western donors like the U.S., and given Hun Sen a free hand to move against organizations whose presence in Cambodia he has always resented,” Mr. Strangio said.

“The ‘UNTAC era’, a highly contingent period in which Cambodia saw its political space flung open to a range of foreign interventions, is quickly coming to a close,” he added.

“In many ways, the country is reverting to its authoritarian historical mean.”

The meteoric rise in internet access—predominantly Facebook—and the subsequent diminishing influence of CPP-controlled media has also been cited as a reason for rising anxieties among the ruling elite over its control of information.

“Getting the government’s message out is increasingly costly and it is harder and harder to be the dominant voice,” Mr. Gillison said.

“Rather than rely on CTN [Cambodian Television Network], Kampuchea Thmey and Bayon, the CPP’s strategy at this point may be to stifle criticism at the source—before it can be shared on Facebook or broadcast on nationwide radio—by shutting down the people and organizations that are most practiced learning the truth,” he added.

Speaking in his office on Thursday, Information Minister Khieu Kanharith refuted any accusation that the government was going after the Daily in an effort to muzzle critical voices, and maintained the newspaper was being targeted purely due to its failure to pay its taxes, even though the threatened closure was coming without due process.

“I believe there are many newspapers that criticize the government and they are still around,” he said, citing the opposition-aligned Moneaksekar website.

Radio Free Asia and Voice of America—two U.S.-funded radio services that have similarly come under attack from the tax department and whose local broadcasters have been shut down or have stopped carrying their content—are also still around, Mr. Kanharith noted.

“Radio Free Asia has not been off too. Please think again. So has [Voice of America]. Some radio stations have been broadcasting, but they are legal,” he said.

Lee Morgenbesser, author of “Behind the Facade: Elections Under Authoritarianism in Southeast Asia,” said the recent actions likely illustrated a wider shift by the Cambodian government toward the more authoritarian models of its eastern and northern neighbors.

“The early warning sign was the amendments to the Law on Political Parties,” he said, in reference to widely criticized changes to the law that many believe are solely aimed at targeting the opposition CNRP.

“This set the stage for a broader transformation of the political system, which would bring it more into line with Laos and Vietnam.”

What’s next?

If the Daily is shuttered after 24 years, Mr. Morgenbesser predicted the Post could encounter problems next.

“The Phnom Penh Post should certainly be on alert, but the media crackdown will probably stop after them. Besides the English dailies, the number of outlets trying to hold the government to account is already limited,” he said.

Despite emerging relatively unscathed from legal wrangles in the past, former editor Mr. Gillison said he believed the Daily’s days could be numbered.

“I am far away, but this time feels different to me. Hun Sen has fewer reasons to spare The Daily than in the past and could be acting to guarantee dominance in next year’s elections, which he may not win fairly,” he said.

“After the coup in 1997, Hun Sen hired lobbyists to rehabilitate his image in Washington, which had put restrictions on aid to Cambodia,” he said. “He may feel he won’t need to this time.”

(Additional reporting by Len Leng)