In the summer of 1978, the orchestra of the Democratic Kampuchea Broadcasting Company met in Phnom Penh to record some songs.

Books had been burned and musicians murdered, but the orchestra had been spared to allow them to spread harmonies of peasant revolution across the country.

“The bright red blood was spilled over the towns and over the plains of Cambodia, our motherland,” its singers crooned to the visiting Swedish-Kampuchean Friendship Association, which eventually produced an LP of the recording.

“On the 17th of April, under the revolutionary banner, their blood freed us from a state of slavery,” the song continues.

For the three years, eight months and 20 days of Khmer Rouge rule, songs such as “Our Rural Area Has Transformed Completely” and “The Heroic Might of Revolutionary Soldiers Restores Roads” served as the state-sanctioned soundtrack to the regime’s brutal reign.

Broadcast over Khmer Rouge-controlled radio stations across the country, the songs trumpeted the valor of Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) soldiers and denounced their imperialist enemies. The lyrics provide instructions, many of them quite literal, for ushering in the next phase of revolution, according to a paper authored by a group of Kent State University academics and published last month in the journal GeoHumanities.

“Songs were used as a form of public pedagogy to identify specific environmental problems and how these were to be overcome,” the paper says. “As the agrarian landscape was transformed through physical labor…so, too, was the citizenry of Democratic Kampuchea to be mentally and behaviorally transformed.”

The Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) has archived and transcribed roughly 150 Khmer Rouge songs, some donated by former cadre.

The songs evoke visions of laborers irrigating gridded rice fields and gory, valorous victory over American and Vietnamese enemies. Performed by musicians whose identities were never recorded, they were designed to be the first step in eradicating the cultural remnants of the “oppressor classes,” and building a “revolutionary culture, literature and art of the worker-peasant class,” according to the CPK’s 1976 Four-Year Plan.

Those cultural remnants included a rollicking rock scene now widely considered to be a high note in Cambodia’s musical history.

After King Norodom Sihanouk declared independence from France in 1953, the rock scene “built and built until brightness came to Cambodia,” according to radio personality Seng Dara, who has researched and written books on the era.

“Businessman started opening shops to sell records” and the U.S. Armed Forces Network began broadcasting to troops in Vietnam, Mr. Dara explained, making stars out of musicians like Sinn Sisamouth and Ros Sereysothea.

The fusion scene took a psychedelic turn in the late 1960s and early ’70s before grinding to a halt on April 17, 1975, when the Khmer Rouge stormed Phnom Penh.

“All musicians [were] sent to the countryside,” Mr. Dara said. The regime banned music from past eras and “killed nearly all the composers. The musicians who [could] play traditional music, Pol Pot made them make music for him.”

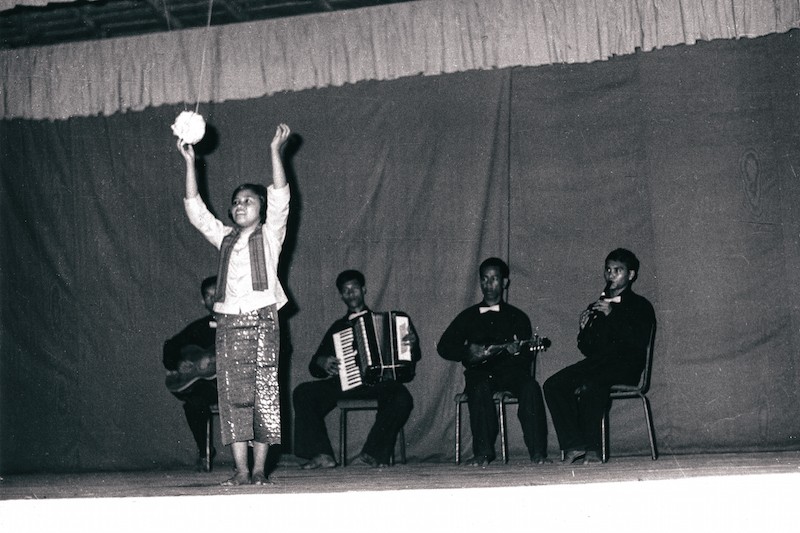

Ballads made for the slow cadence of village life—weddings, festivals, rice harvests—were stripped of their original lyrics and rewritten to the beat of the CPK’s ideology. The songs were blasted from loudspeakers and performed by traveling art troupes accompanied by hoe- and shovel-bearing dancers.

“Female peasants in our cooperative are working hard to transplant young rice seedlings,” read the lyrics to one of the songs. “They are laughing happily and singing songs together. Their surrounding environment looks so peaceful and beautiful.”

Other songs were infused with the gore of war.

“When you died, friend, you were still naked, chest and stomach torn asunder, liver and spleen gone,” read the lyrics to a children’s song. “When you died, friend, you reminded me that the hated enemy had swallowed Cambodia.”

Haing Ngor, a Cambodian-American actor best known for his leading role in “The Killing Fields,” recounted a chilling performance by one of the troupes in his memoir “A Cambodian Odyssey.”

The performers chanted “‘Blood avenges blood’ at the top of their lungs,’” Mr. Ngor writes. “Both times when they said the word ‘blood’ they pounded their chests with clenched fists, and when they shouted ‘avenges’ they brought their arms straight out like a Nazi salute, except with a closed fist instead of an open hand.”

Muth Ream, 58, was a traditional dancer before the Khmer Rouge took power. Later, she was assigned to transport food and other supplies for the regime. She recalled the songs evoking sadness rather than revolutionary fervor.

“Most of the songs of the Khmer Rouge I used to hear were mainly encouraging people to sacrifice their life for Angkar, but I don’t remember those songs well because I wasn’t careful to remember them,” she recalled on Monday.

“I spent most of my time living and sleeping in the forest. When I heard those songs broadcast on the radio, I missed my family.”

The music scene remained a state-run affair under the rule of the Vietnamese who overthrew the Khmer Rouge in 1979, Mr. Dara said.

The songs were “composed to admire Vietnam, admire the new regime, admire the new leader,” Mr. Dara said. Music from the Khmer Rouge, Lon Nol and Sihanouk regimes were all forbidden, he said.

“Cambodian people didn’t hear the light again until 1991,” he said.

CDs of Khmer Rouge songs are still available in some markets, according to Mr. Dara. He once played one on his show, he said, only to receive a series of angry calls.

“‘You made me feel pain; you made me angry,’” he was told.

Youk Chhang, executive director of DC-Cam, said some survivors had embraced the music as a way of taking back their pasts.

“The Cambodians—many genocide survivors—continue to sing today, including songs written by the Khmer Rouge as a mean[s] to reclaim their humanity and healing,” he said in an email.

Ms. Ream, who now lives in Banteay Meanchey province, is not among them.

“Since the fall of the Khmer Rouge, I have avoided listening to Khmer Rouge songs, because it is just painful to hear them,” she said.

(Additional reporting by Kuch Naren)