When Jack Dunford first entered a Cambodian refugee camp in 1981, it was a startling sight for him—one that he sought to explain through photographs as well as words.

The British national, who was living in Bangkok as a traffic engineer at the time, ended up at the camps at the age of 34 through his involvement with the Thai National Church, which supported small relief projects along the border.

“I was a keen amateur photographer,” Mr. Dunford said in an interview Sunday. “Because this was the first time I was involved in anything like this, I wanted to know why — why are they refugees? What’s happening to them?

“We had visitors coming through [the church] all the time, and I was trying to take pictures that told stories. There was no concept of a digital age, but I always have a sense of history, so I always wrote the name, location and date,” he said.

Through this process of cataloguing his observations, Mr. Dunford, now 68, amassed a remarkable collection of photographs, slides, newspaper cuttings and personal reflections from his time at the camps along the Thai border.

Last week, in his first trip to Phnom Penh, he handed 144 film slides, an audio cassette and 1,220 digitized images from at least 13 Cambodian refugee camps to the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam).

“I started to think, well, there might be pictures of people there that might be the only picture that exists of their time as a refugee,” he said. “Now wouldn’t it be wonderful if there could be some way that this could be somewhere that people could come and look?”

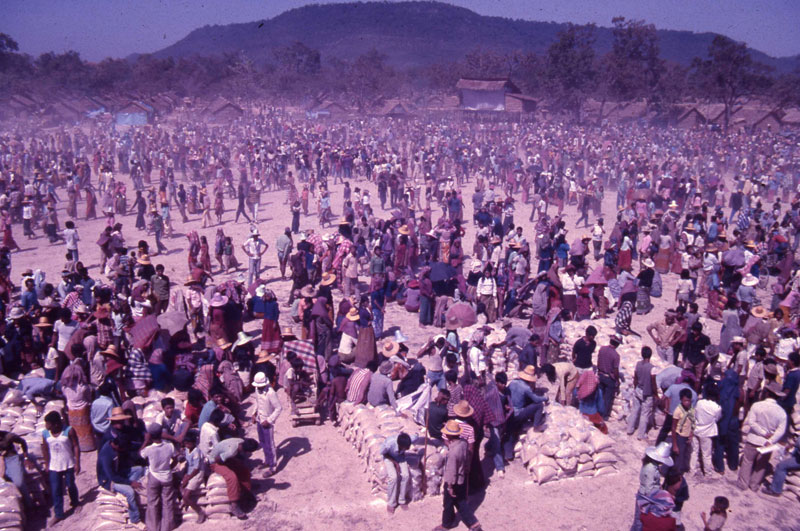

Hundreds of thousands of Cambodians spent time in the camps on either side of the Thai border in the 1980s as war continued to grip Cambodia following Vietnam’s overthrow of the Khmer Rouge.

The Khao I Dang camp on the Thai side of the border, which was established after Thailand opened its border for a few months in 1979, was at one point home to more than 150,000 people.

As the U.N. and humanitarian organizations flocked to the border in response to the crisis, Mr. Dunford saw an opportunity to put some of the church’s budget to good use.

“I supported things like the International Rescue Committee soap-making project in Khao I Dang,” he said. “Handicap International was making Pol Pot shoes—the kind made out of tires. It was such a small thing, but it gave me access to the camps.”

The camps were “a whole new world to me,” he said of his first visit to the area in 1981, which led to his 30-year career as the executive director of The Border Consortium.

“It was these huge camps and I was struggling to get my head around it all. It was like an aid city…. I mean, the camps were not nice, they were very crowded. My whole mindset was ‘what’s it all about?’”

Seeking to answer this question, Mr. Dunford began carrying his camera with him every time he returned to the camp, to capture his own images.

“Film was expensive—but I wanted them to be mine. So I literally paid for film and for them to be developed. In those days, to take a roll of film was an investment. I might take a roll on an average trip,” he said.

Nearly all of his photos of Cambodian refugees were taken during the Vietnamese occupation of the country, during which resistance fighters set up bases along the Cambodian side of the border.

Mr. Dunford’s trove includes images from Khao I Dang that show refugees fetching water and gasoline using whatever hoses and vessels were available to them. In another photograph of the camp, taken from an elevated position, rows and rows of thatched huts stretch to the horizon. Another image shows a sign, written in broken English, extolling the virtues of the Thai government. “We are the good refugees who loyal the royal King of Thailand,” the sign says.

On one occasion, Mr. Dunford even managed to sneak a camera into a Khmer Rouge-controlled camp. “You had the sense of oppression in there,” he said. “The people didn’t seem to smile.”

Youk Chhang, executive director of DC-Cam, who was himself a refugee at Khao I Dang, said Mr. Dunford’s recent donation “means that another broken piece of our society has been reconnected.”

“Perhaps the photographs bring people closer to understanding it better,” he said. “Being able to reflect on what it was like and who they are now is significant.”

Mr. Dunford is now seeing the potential importance of his images, which spent 30 years in a box.

So far, two women have recognized either themselves or family members in photographs taken over his decades of work in the region, he said, adding that he hopes that number will continue to grow.

“I’m feeling very engaged again,” he said. “Even just going around DC-Cam—I do care. I have something precious; these are memories.”