The March 18, 1970, overthrow of Cambodia’s head of state, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, continues to be on my mind to this day and has kept me busy sorting out information for the past 45 years. Unlike many Cambodians who turned against the Prince, I was very close to him before his overthrow. I was on the Prince’s information team as an editorial assistant. Upon my return from the U.S., he gave me an office at his official Sangkum Printing Plant and put me in charge of proofreading and editing copies of articles, statements and speeches he made.

At the printing plant, we paid particular attention to his political magazines, Kambuja and Le Sangkum, which were published in French and English. On that day of March 18, I was reviewing the last copy of Kambuja which had just come out of the press when the plant manager who supervised all the publications asked me to join him for a private discussion. That copy of Kambuja, incidentally, turned out to be the last copy of the glossy monthly. The Prince would never see that issue. I have kept it with me to this day.

Prince Sihanouk had been away in France for more than two months, and the country was in major turmoil. The National Assembly was in the process of debating serious charges against the Prince in his absence. Those charges included corruption, lavish spending of the national budget, mismanagement and, above all, the Prince’s collusion with Communist Vietcong and North Vietnamese forces, known as VC/NVA, while the war raged on next door in South Vietnam and the Americans were bombing Cambodia’s border areas. It was his secret authorization for the Communist Vietnamese to establish bases in eastern Cambodia that

sparked the gravest and most unprecedented debate at the National Assembly. Representative after representative took the floor and denounced the Prince for breaching Cambodia’s policy of independence and neutrality, which the Prince himself had adopted for Cambodia.

For three weeks, the VC/NVA sanctuaries on Cambodian soil had led to fervent demonstrations right at the door of the National Assembly, with banners and slogans demanding that the government ensure that those 50,000 Vietnamese Communist troops left Cambodia immediately. On the morning of March 18, negotiations between the Cambodians, headed by Kim Eng Kurudeth and representatives of the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese, failed to meet Cambodia’s demand for the withdrawal of these Vietnamese troops. At the height of the demonstrations, people sacked and burned down the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese embassies in Phnom Penh to the ground.

Meanwhile in Paris, Prince Sihanouk, who had been away from Cambodia since January 6, refused to meet with the government’s envoys, former Prime Minister Prince Norodom Kantol and Foreign Minister Yem Sambaur, for talks on the mounting crisis. Moreover, he accused his top generals and leaders of his own party in Phnom Penh of colluding with the Americans, and words of threat from the angry prince had reached Phnom Penh overnight. People’s anger boiled, the National Bank was in trouble, the city trembled and the Prince was enraged.

At noon, I met Ros Chet Thor, the plant manager, and tried to work together with him to monitor information on the mounting crisis while, at the National Assembly, Representative Trinh Hoanh brought the strongest charges yet

against the Prince. Charles Mayer, the French senior adviser to the Prince, stopped by briefly and compared notes with us. Mayer hinted that anytime soon, between noon and 2 p.m., the most critical decision would be made one way or the other and we should be careful not to jeopardize any official statement. We then split for lunch and for some fresh air. The atmosphere was choking us.

Mayer was right. At 1 p.m., I heard the last words from Trinh Hoanh: “I hereby withdraw my confidence from Samdech Head of State.” The National Assembly, in a unanimous decision, voted to withdraw confidence from Prince Sihanouk and empowered House Speaker Cheng Heng as head of state.

In Beijing, Prince Sihanouk met China’s Zhou En-lai and North Vietnam’s Pham Van Dong and, together with his erstwhile leftist detractors, formed the Royal Government of National Union of Kampuchea, better known by its French acronym GRUNK. The exiled government was announced on May 5 and immediately recognized by China. Subsequently, in his Beijing radio messages, the Prince called for a large-scale popular uprising against Lon Nol and against the Phnom Penh leadership.

Meanwhile, on March 29, ten days after the removal of Prince Sihanouk, the VC/NVA, dormant until this time in their Cambodian sanctuaries, launched a lightning offensive against government positions in the country and against all provincial defense perimeters, with their advance troops rushing toward Phnom Penh and advancing as close as Sa’ang district in Kandal province, only about 20 km south of the capital. With only a ragtag band of 35,000 men armed with mismatched weapons, the Cambodians stood up to

repel war-hardened VC/NVA. Prime Minister Lon Nol, who remained at the head of the government with his entire cabinet unchanged, issued a General Mobilization draft and asked the Cambodians to organize 100-house self-defense units. It was the time of the 24-hour soldiers, when volunteers underwent brief military training and were sent to the battlefields on Pepsi-Cola trucks to stop the VC/NVA advance. I too enlisted in the army, while my mentor Ros Chet Thor, the French-educated manager of the Prince’s printing plant, secretly left Phnom Penh and joined the core group of leftist guerrillas in Omlaing village in Kompong Speu. The group was soon to become the central Khmer Rouge organizing committee.

Thanks to dedicated volunteers and their brave commanders, VC/NVA progress was checked and breathing space was created for the Lon Nol government to continue defending the Cambodian people against the enemy onslaught for the next five years until 1975 when the Americans evacuated Southeast Asia and left a chaotic disaster for Cambodia and its people.

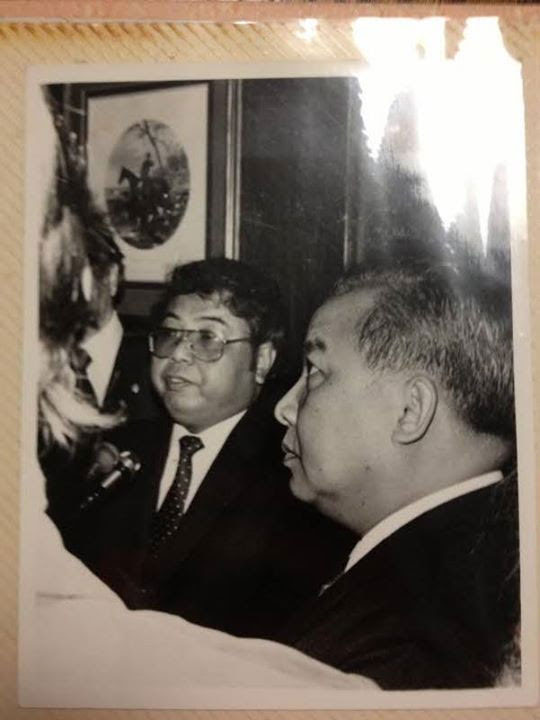

In 1981, I introduced Prince Norodom Sihanouk at a reception in Washington after he had arrived there from Pyongyang, North Korea. He told the audience the story of his house arrest by the Khmer Rouge and vowed to never work again with the Khmer Rouge who were, he said, “the killers of my people.” By this time, over two million Cambodians had died of executions, diseases, overwork and starvation under the Khmer Rouge rule known as Democratic Kampuchea.

Chhang Song was Minister of Information for the Lon Nol-led Khmer Republic from 1974 to 1975. He now lives in Long Beach, California.