Lon Nol was a delusional leader who sobbed during a meeting with an American general while desperately requesting assistance in fending off the communist insurgency that would eventually result in the Khmer Rouge overthrowing him, according to declassified U.S. intelligence files.

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) on Tuesday released more than 12 million pages of documents online—including about 12,000 files on Cambodia—that were previously only available by visiting the U.S. National Archives in Maryland.

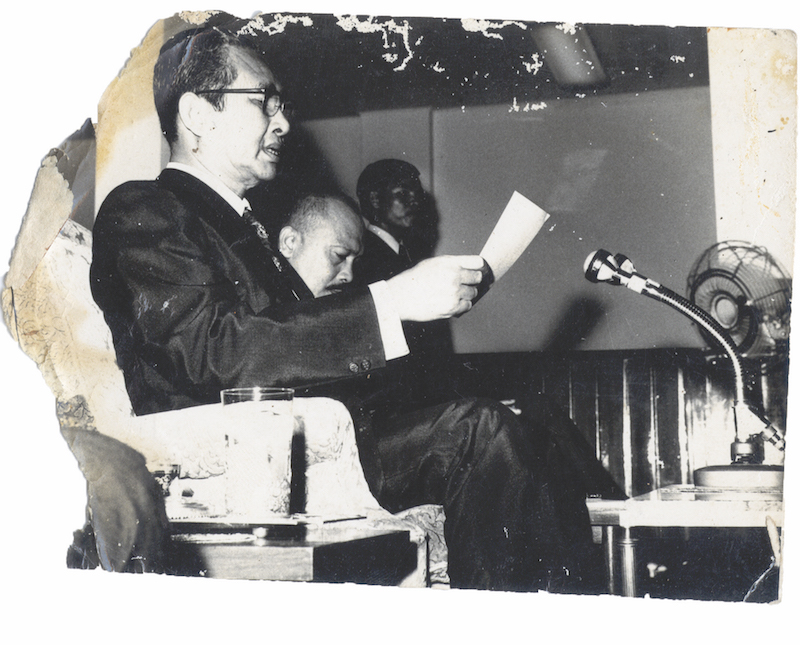

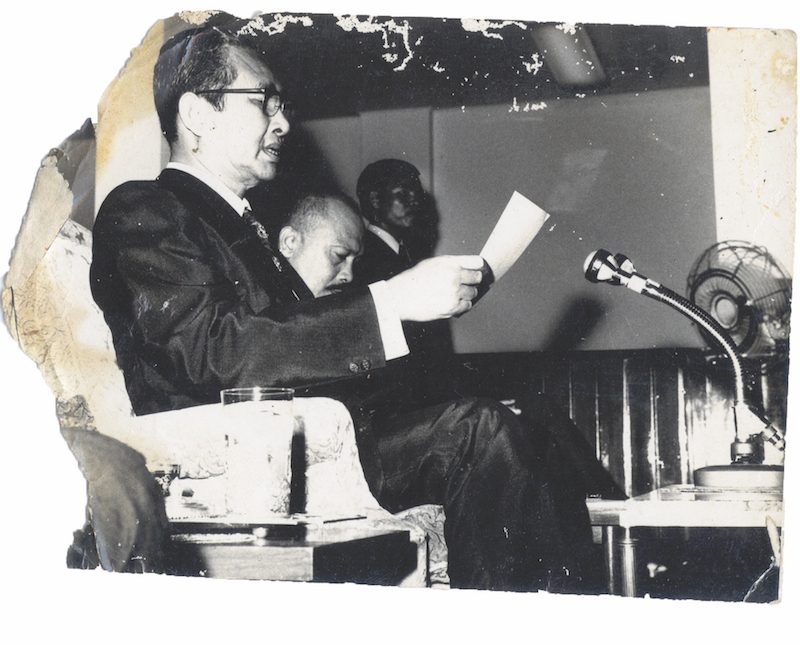

The huge database includes in-depth insight into the U.S.’s dealings with—and concerns over—Lon Nol, the general who took power from Prince Norodom Sihanouk in March 1970 and received backing from former U.S. President Richard Nixon’s government in an effort to root out Vietnamese communists during the Second Indochina War.

In one document, written just over a month after Lon Nol took power, the CIA’s “Cambodia Working Group” claims that the new regime “enjoys the support of the great majority of the Cambodian people” and that “the atmosphere in the capital has been generally calm and controlled since Sihanouk’s ouster.”

However, it notes the threat that Vietnamese communists could pose to the regime, particularly if Prince Sihanouk was to join forces with the guerillas.

“Aside from the overt military threat from the Vietnamese Communists, the major threat to the present government is the possibility that Sihanouk will return and, with Vietnamese Communist assistance, lead a jungle-based resistance movement,” it says.

“Sihanouk could probably attract a substantial following, but it is not presently possible to determine just how large or effective this would be.”

The prince’s call for the peasantry to join the Khmer Rouge shortly after his overthrow helped the Cambodian communists’ ranks swell from about 15,000 in 1970 to around 125,000 by 1972.

About a year later, the Khmer Rouge had taken de facto control over large swaths of the country and distanced itself from the Vietnamese communist movement.

In 1970, however, the authors of the working group’s report were highly skeptical about how much of a threat the mysterious communists in the east actually posed.

“The indigenous insurgents, or ‘Khmer Rouge,’ represent the main indigenous force. Although hard evidence is lacking, the total numerical strength of the Cambodian insurgents probably does not exceed 5,000,” it says.

“There is no proof that this three-year-old insurgency is a coordinated movement but there is evidence that the insurgents along the Eastern border receive arms and direction from the Viet Cong,” it says, adding that the movement had little support and its “terrorist tactics” had alienated much of the peasantry, but that they could emerge as a “greater problem” in Phnom Penh.

About a month later, a memorandum from then-National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger to Richard Nixon contained a report from an American general, Alexander Haig, who had met Lon Nol in Phnom Penh. The general described Lon Nol as an “emotional” and unrealistic leader who was desperate for further U.S. support to keep the communists at bay.

“It is…evident that Lon Nol is badly shaken if not desperate that we must move promptly with more concrete manifestations of U.S. support,” General Haig says.

“You will note that my efforts were to keep an emotional and not very realistic leader thinking along practical lines,” he adds.

In a transcript from the meeting, Lon Nol suggests that the U.S. and Cambodia “could perhaps train and fight together” against the communists in the northeast of the country.

In response, Gen. Haig promises artillery including rifles, ammunition, machine guns, mortars and “perhaps some rockets,” and says air support could be a possibility after Lon Nol repeats his request for U.S. soldiers on the ground.

“I hope that you are ready to aid us. We feel the ground trembling under us,” Lon Nol later says.

As the general reiterates U.S. support for the new regime, the document notes that Lon Nol succumbs to tears.

“At this point General Lon Nol broke down and sobbed. He then got up and went to the other end of the room until he regained his composure,” it says.

In another document, a summary of a meeting between Richard Nixon and officials in Washington in June 1970 outlines how he stated the U.S. “must take whatever heat is necessary” in preserving the “neutrality” of Cambodia and fending off the insurgency.

“Everyone should take a confident line with the press and in backgrounders. The line that ‘Cambodia is doomed’ must be stopped,” the president is cited as saying.

“It is worth taking risks. Our objective is more to maintain a non-Communist, independent government rather than backing any particular government,” it says.

In a gushing letter to Lon Nol about three years later, following the Cambodian leader’s request for medical treatment in New York, Richard Nixon lauds Lon Nol’s patriotism and leadership during a period in which he allowed the U.S. to conduct devastating bombing campaigns in areas of Cambodia where Viet Cong forces were suspected of hiding out, destroying villages and arousing fear that helped the Khmer Rouge come to power.

“I have followed with great care developments in the Khmer Republic over the past months. I commend you on the wisdom of your decisions to broaden your government and to allow a group of able men assist to you in guiding the destiny of your people,” the U.S. president wrote.

“In this, you have again displayed the selflessness and sense of duty which marks you as the Republic’s foremost patriot.”

However, a CIA document from around the same time claims that there were “some indications that dissatisfaction with the performance of the Lon Nol government” had made Prince Sihanouk—who was traveling around Khmer Rouge-controlled areas with the movement’s leaders—more acceptable to some circles in Phnom Penh. It also notes that “most Cambodian army officers below the top level and their troops would support Sihanouk if he returned.”

Despite this, the intelligence agency believed that the communists were only supporting the beloved prince for “tactical reasons.”

They were correct.

Prince Sihanouk was eventually put under house arrest by the Khmer Rouge after they took power, ushering in a four-year reign during which an estimated 1.7 million people died from executions, starvation and disease.

Lon Nol fled to Hawaii and died in California in 1985 at the age of 72.