Ferried Away

Ferried Away

LOEUK DEK district, Kandal province – Before the sun casts its light on the Neak Loeung ferry port every morning, commuters begin arriving in buses and cars, on motorbikes and horse-carts. At the crest of the riverbank, chains slung between concrete pillars bring them to a halt. And there, even before their engines are shut down, the peddlers pounce.

Teenagers mob the cars, offering drinks, sweets and cigarettes. Elderly women weave through mazes of vehicles, balancing trays of bugs or betel leaves on their heads. Sunglasses are for sale. Eggs of all sizes. DVDs, donuts and toy dogs with heads that bobble.

And then there are the beggars: toddlers with runny noses wearing no more than grime, blind men with big smiles, and spindly old women who survived civil war and genocide only to end up pleading with strangers for cash.

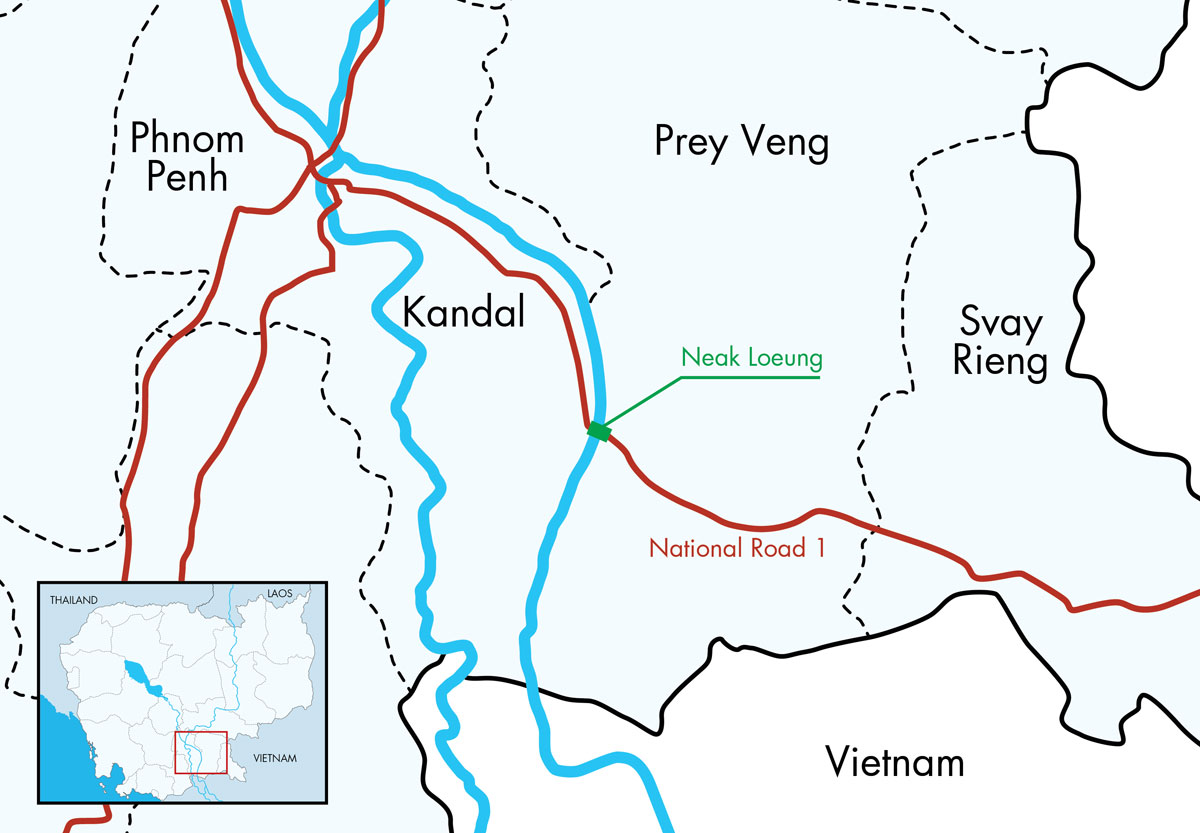

About 60 km southeast of Phnom Penh, where the Mekong splits Kandal from Prey Veng province, the Neak Loeung ferry crossing turns thousands of people into captive consumers each day as they queue for a boat to take them across the river.

The area has also become a second home for those seeking to sell to and beg from these crowds. Many of the hundreds who beat the sun there every day are following in their parents’ footsteps. Some families arrived as soon as the ferry service resumed in 1979. Now, though, they all need somewhere else to go.

A few kilometers upstream from the chaos of the ferry landing, Prime Minister Hun Sen will on Monday open the Tsubasa Bridge, a $127-million suspension bridge that will significantly cut the travel time from Phnom Penh to Ho Chi Minh City and fill a vital gap in the planned expressway that will link Ho Chi Minh to Bangkok via Poipet City.

For those who have carved out a living around the ferry landing, this new bridge represents the end of an era.

“Now, I don’t know what to do,” said Chou Nang, a 67-year-old who has worked the dock since 1979. “When the ferries stop crossing, the cars will stop coming and I will have no one to sell to.”

A fixture at Neak Loeung since it reopened for civilians following the fall of the Khmer Rouge, Ms. Nang has an exalted position in the hierarchy here. She sits out of the way of the moving vehicles, smiling from behind a neatly rolled stack of betel leaves, which she sells wholesale to other women who then zigzag between cars looking for buyers.

Born here in Loeuk Dek district in the 1940s, Ms. Nang can divide her life into three distinct periods: youth, war and working the ferry landing. All of them, she has spent at Neak Loeung. She recalls the August 1973 bombing of the port by the U.S., her husband being hauled away by the Khmer Rouge in 1978, never to be seen again, and Vietnamese troops coming across the Mekong in the days before the Khmer Rouge were toppled.

“At first I was scared,” she said of that day in late 1978. “But those who spoke Vietnamese told me that there was no need to be scared, as they had come to help, to liberate us.”

While vivid, those memories are all distant now, as Ms. Nang prepares to move, happily, into a fourth phase of life: “I will let my son look after me,” she said.

Though she holds no resentment toward the bridge that will force her relocation, the timing of its opening, a week before Khmer New Year, is disappointing. Over the Khmer New Year and Pchum Ben holidays, the chaos increases significantly in Neak Loeung as thousands of families leave Phnom Penh for the southeastern provinces of Prey Veng and Svay Rieng. Vehicles queue for kilometers. Families sleep overnight. The road turns into a shantytown. And the locals reap a windfall.

“On a normal day, I can earn 10,000 riel [about $2.50], but during the holiday, in three or four days I can earn 500,000 to 600,000 riel [$125 to $150],” she said, adding that she brings a sleeping mat and a mosquito net so she can cater around the clock to the holiday crowds.

Pouch Sarath, a 52-year-old ferry captain from Peamro district on the Prey Veng side of the Mekong, was completing his final shift at the helm of one of the four state-owned vessels on Wednesday.

As he guided the 140-ton Ta Prohm on its five-minute journey across the river, he said he was unsure exactly what the opening of the new bridge would mean for his future.

Along with the Peace 2, the Vishnu and the Samaki, the Ta Prohm is set to be relocated to Phnom Penh, where it will be put to work on the route that links the city to Arei Khsat in Kandal, according to provincial governor Mao Phirun.

Mr. Sarath said that, as a staunch civil servant, he “would not be opposed if the state assigns me somewhere else.”

“I am a little bit dissatisfied because I rely on this salary, but there is nothing we can do,” he added. “The country needs to develop.”

Damnak Toek (A Drop of Water, in English) is a local NGO with a child-focused project operating at Neak Loeung. In its 2013 report, “Neak Loeung, Cambodia: Street Children Survey,” the organization says that, in one day, 247 street children were identified around the dusty port that connects Phnom Penh to two of the country’s poorest provinces.

Damnak Toek offers a drop-in center, education, vocational training and medical care for children and their families in the area. With the opening of the bridge, however, it is unclear how the program will evolve when commuters no longer have to stop and wait for a ferry.

“The area will see change, dynamic change,” said Sebastien Marot, executive director of Friends International, which partners with Damnak Toek in its Neak Loeung project. “We are wondering how it will change, and we are working so we are ready for change.”

According to Damnak Toek, 34 percent of 160 street children surveyed at Neak Loeung will move to Phnom Penh when the bridge is opened. Just 9 percent said they will stay in Neak Loeung. A further 30 percent said their future remained uncertain.

On Wednesday, Tha Chanthib, 20, took a break from selling drinks in the searing sun. Sporting a big-brimmed floppy hat and long-sleeved floral shirt, she said she began her career at Neak Loeung as a 10-year-old selling cigarettes and candy, and that the hundreds of sellers and beggars who depended on stalled commuters here are like a family.

“This place will become quiet,” she said. “I will miss all my friends—the people who sell here together—and I will miss the bucket that I used to hold.”

With no formal education, a place in one of the country’s garment factories seems likely for Ms. Chanthib. “I don’t believe that it will be better than my job now,” she said. “But I have nothing else to do.”

Thirteen-year-old Ho Sophean dropped out of school about six months ago to sell bottled water at Neak Loeung. Already, she is one of the best in the business, eagerly darting between cars and returning to the shade to refill her cooler more often than most.

As she joked with her colleagues about stealing customers from one another, she said she would miss that daily battle when the bridge opens. The cornfields about 1 km from the ferry landing, she said, were likely her next destination. “I have no other means to make money.”

For about 500 people, serving the thousands of commuters who cross the river at Neak Loeung each day is key to survival, according to Chum Vuthy, a government employee who sells ferry tickets. He says that hundreds more have already left the area to work in factories, anticipating the breakdown of their business. But sewing clothes or gluing shoes is not an option for Hieb Wei.

Mr. Wei, 34, is almost completely blind and is cared for by his aunt and uncle on the eastern bank of the Mekong. Each morning he rides the first ferry to the western bank, where he teams up with Srey Pov, a boisterous 16-year-old girl who guides him through the traffic to collect donations from sympathetic travelers, which they then split 50/50.

“I can see just enough to make sure that she gives me half,” Mr. Wei said, laughing.

Business at Neak Loeung is relatively good for Mr. Wei and his adolescent sidekick. While the majority of sellers report earnings of about $2.50 a day, Mr. Wei said he was pocketing between $5 and $7.50 in each 14-hour shift, with Srey Pov getting the same.

As he sat on a wooden bed with two other blind men, he said that when the new bridge eliminates his meal ticket he would search for an NGO that might be able to offer him some assistance. Still smiling, Mr. Wei said he was not bitter about the impending change.

“I worry about having nothing to eat in the coming days,” he said. “But I don’t feel angry because we have to develop the nation.”