In August 1978, as reports of Khmer Rouge atrocities began to flow out of Cambodia, Gunnar Bergstrom arrived in Phnom Penh on a mission.

He was hoping to discredit these reports as fabrications of the U.S. and other Western countries, and prove that the Khmer Rouge were an upright group of freedom fighters who had liberated their nation from capitalist oppressors.

“In the beginning, we wanted to believe that all of this was propaganda and that everything they said about the Khmer Rouge was a lie,” Mr. Bergstrom, now 65, said from his home in Stockholm last month.

Mr. Bergstrom had become one of a select few Khmer Rouge supporters from Western countries who were granted access to the closed-off mass worksite that was Cambodia under the Pol Pot regime.

With a political conscience shaped by the Second Indochina War in the 1960s, the young Marxist had played an active role in Sweden’s anti-war movement, which helped turn the tide of public opinion against the U.S. presence in Vietnam. As Richard Nixon’s government began its carpet bombing campaign inside Cambodia in 1969, Mr. Bergstrom’s attentions moved across the border.

Perceiving the Khmer Rouge’s overthrow of Lon Nol in April 1975 as a liberation from a corrupt regime backed by imperialist Western superpowers, Mr. Bergstrom helped establish the Swedish-Cambodian Friendship Association a year later.

In August 1978, following two years of negotiations—during which an increasing number of tales of mass murder and starvation began to trickle out of Cambodia—Mr. Bergstrom stepped onto Phnom Penh’s Pochentong Airport runway alongside three comrades, Maoist author Jan Myrdal, Marita Wikander, and Hedvig Ekerwald, with hopes of debunking the horror stories as CIA propaganda.

Driving through the capital’s desolate streets, which had been emptied by the regime as it evacuated its residents shortly after taking power in 1975, Mr. Bergstrom encountered a surreal scene.

“It was like a science fiction film, you know? People asked, ‘Were you not shocked and horrified?’ And we had to tell people that we expected it. We knew it was empty. We saw an empty city,” Mr. Bergstrom said.

“The things I remember thinking, and it was 40 years ago, is that we had, so far, defended the Khmer Rouge. I had never said that there were no killings and no murders because I realized there had been a war…I realized there had been some killings in the beginning.

“I thought maybe the refugee stories are about that. I hoped that the killings were over now. We defended the evacuation of the cities with the arguments that the Khmer Rouge had given us,” he said.

After spending a couple of days in a residential area of Phnom Penh, the group was taken to Kandal province to see a worksite. Shocked by the squalid conditions workers were toiling in, the initial seeds of doubt were sowed in Mr. Bergstrom’s mind.

“The interesting thing was this was the poorest part with the most shocking images of the whole trip, and they started there,” Mr. Bergstrom said.

“Lots of people living in bombed houses, ruins, huts that were hardly standing up and people swimming, planting rice with hardly any resources, but that’s what they showed us on the first day. Maybe they decided, ‘We’ll show them the poorest part first.’ I don’t know,” he said.

Despite his shock in Kandal, Mr. Bergstrom said most of his doubts were alleviated as trips to Siem Reap, Kompong Cham and Kampot provinces revealed people working in “acceptable” conditions. They began to resurface, however, as their minders repeatedly ignored requests to meet “new people” who had been evacuated from the cities.

“When they didn’t want to show us one I thought maybe they had killed them all,” he said.

As the carefully orchestrated trip continued, differences in opinion between the members of the communist delegation began to rise to the surface, Mr. Bergstrom said, although he kept quiet about most of his doubts.

Upon witnessing children melting down Coca-Cola bottles to make vials for injections, and laboring on boats in what is now Preah Sihanouk province, Mr. Bergstrom relayed his unease to Mr. Myrdal. The leftist writer dismissed his concerns, claiming that the children were working in conditions similar to those in Sweden 200 years ago.

Toward the end of the trip, the delegation was finally granted an interview with Pol Pot. The secretive leader gave long, rambling answers and the interview broke little new ground. Afterwards, the group dined on oysters with Pol Pot and Foreign Minister Ieng Sary.

During a bathroom break, Mr. Bergstrom had a conversation with Ieng Sary in which he attempted to persuade the high-ranking official—who died in 2013 while on trial for crimes against humanity at the Khmer Rouge tribunal—to open up the country to the outside world.

“At that time I still supported the Khmer Rouge and I told him, ‘You have nothing to hide. Being closed like this always creates rumors that you have got something to hide.’ He made a note of this and said he would think about it.”

Despite the doubts he said he entertained, Mr. Bergstrom recorded a radio broadcast for Radio Phnom Penh hailing the achievements of the Khmer Rouge before returning to Scandinavia.

“At that time I still felt there was something wrong here. Everything that popped up when I came home had started inside of me then,” he said.

“I didn’t want to do this interview where I said everything was fantastic because I had my doubts, but at the same time they were expecting this interview and I don’t know what would have happened if I said no.”

The Swedes were not the only pro-Khmer Rouge Westerners to gain access to Democratic Kampuchea. Marxist academic Malcolm Caldwell—who traveled to Cambodia with journalists Elizabeth Becker and Richard Dudman in December 1978—was gunned down inside the Phnom Penh house where they were staying.

The next day, Ms. Becker and Mr. Dudman took part in a secular funeral ceremony for Caldwell that was overseen by Ieng Sary, who blamed the Vietnamese for his death.

Testifying at the Khmer Rouge tribunal last year, Ms. Becker said that documents from Tuol Sleng security center showed that a group of Khmer Rouge soldiers arrested for the murder were among the last people to be executed at the notorious prison before the Vietnamese invasion.

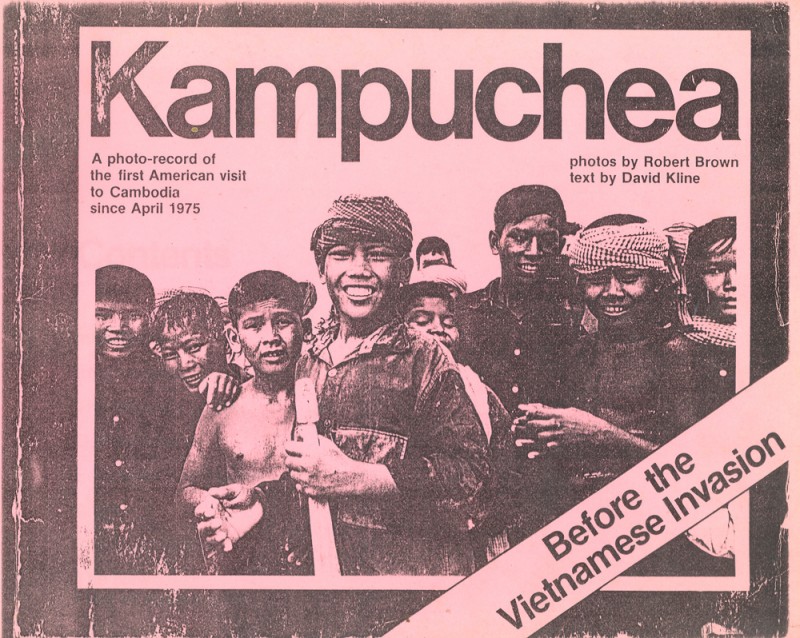

Also granted access in 1978 were a group of American Marxists—David Kline, Robert Brown and Daniel Burstein—who were given a whistlestop tour of the country as killings and starvation were reaching new extremes.

Upon returning, the group published “Revolution: Before the Vietnamese Invasion,” a gushing homage to the Khmer Rouge and its “reconstruction” of society.

“What these journalists discovered was a Cambodia quite different from the horrifying image conveyed in most Western press accounts. They found a people who genuinely supported their government, and a country that was embarking on one of the greatest reconstruction and socialist development efforts of recent time,” the opening page reads.

Later on, the book appears to mock Western reports of genocide and mass executions.

“These charges (always made by people who have never seen the new society) are reminiscent of the wild slanders which greeted China’s liberation nearly 30 years ago. But Kampuchea’s leaders are even being accused of actions against their own people which have never before been seen in human history!” it says.

In an email last month, Mr. Kline, the book’s author, who has since been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and is now a branding and communications expert in Portland, Oregon, attributed his initial support for the Khmer Rouge to post-Vietnam “anti-war naivete.”

“It is tragically clear that in 1978 I failed to grasp (at least immediately) what a horrific genocidal regime the Pol Pot government truly was,” Mr. Kline said.

Recalling standing on a broad avenue in the deserted capital alongside Ieng Sary, Mr. Kline claimed he also began to have doubts about the agrarian revolution transforming the country.

“[A]ll I could hear was a slight whispering of wind and the droning of Foreign Minister Ieng Sary as he stood behind me trying to explain why the capitol city’s 2.5 million citizens had been forcibly removed. He said something about “protecting the population from imminent U.S. and Vietnamese aggression,” he said. “But as he kept talking, all I could think of was, ‘Can this really be human to do such a thing?’”

“This question gnawed at me in the weeks afterwards, even as I struggled with myself to write about ‘revolutionary peasants’ building a ‘new Kampuchea’. But then one day, I knew—No, it’s not human. And the whole socialist mirage just fell away. No more Potemkin Villages for me.”

“So there it is. I made a huge mistake. I have tried to make amends since.”

Mr. Bergstrom finally renounced his pro-Khmer Rouge stance after a two-month tour of Sweden promoting the regime and writing favorable articles about it in the national press.

“At the end of that period I had started thinking about the stories from the refugees, thinking that all those stories cannot be false. I had met refugees at a hearing in Oslo and some of them were quite credible; they were not CIA agents,” he said.

After penning an article in a major Swedish newspaper admitting he was wrong in 1979, Mr. Bergstrom relocated to Northern Sweden and concentrated on a career in drug rehabilitation.

The other members of the delegation—Mr. Myrdal, Ms. Ekerwald and Ms. Wikander—either declined to be interviewed or could not be reached.

However, Mr. Myrdal has continued to maintain that the Khmer Rouge was a force for good. In a 2006 article entitled “I Saw No Mass Murder,” he argued Cambodia would be better off today if Pol Pot had been able to follow through with his revolutionary goals.

“What I should further state is that…I am convinced that if Democratic Kampuchea had been able to continue to follow Pol Pot’s plans to build the country with their own power…then the Khmers would have been in a much happier position today,” he wrote.

Ms. Wikander has remained mostly silent on the trip after it emerged that her Cambodian husband, who was the Khmer Rouge’s ambassador in East Berlin, was killed by the regime after being called back to the country in 1977—around a year before she traveled there.

“When he went back to Phnom Penh, we know now that he was taken away and killed. She didn’t know that of course and she wanted to believe in that revolution for a long time,” Mr. Bergstrom said.

“When she was one of our delegation, the Khmer Rouge had a problem because they realized who she was and that she had been married to the man they had killed.”

Their son later found his father’s name in the records at Tuol Sleng.

In 2008, 30 years after first setting foot on Cambodian soil, Mr. Bergstrom returned to the country for the first time to put on an exhibition of his photos at Tuol Sleng. While writing captions for the pictures, he decided to produce separate captions—or “forbidden thoughts”—in which he recalled the repressed doubts that had begun to set in during his first trip.

“In some photos there was [another] caption and that was what I called ‘forbidden thoughts’—thoughts that came up in the back of my mind and tried to push away,” Mr. Bergstrom said. “If these thoughts were right then it meant I had been wrong all the time and it meant I had to leave this group and all my friends.”

Upon returning to Cambodia, Mr. Bergstrom said he realized it would also be a trip of repentance.

“I realized that I will be meeting people in Cambodia that would have lost brothers, sons, fathers to Pol Pot and I can’t just go there to say, ‘I just want to see your country again,’ or, ‘It would be nice to see Tuol Sleng,’” he said.

“Then I realized that I have to say, ‘Sorry, I was wrong.’”