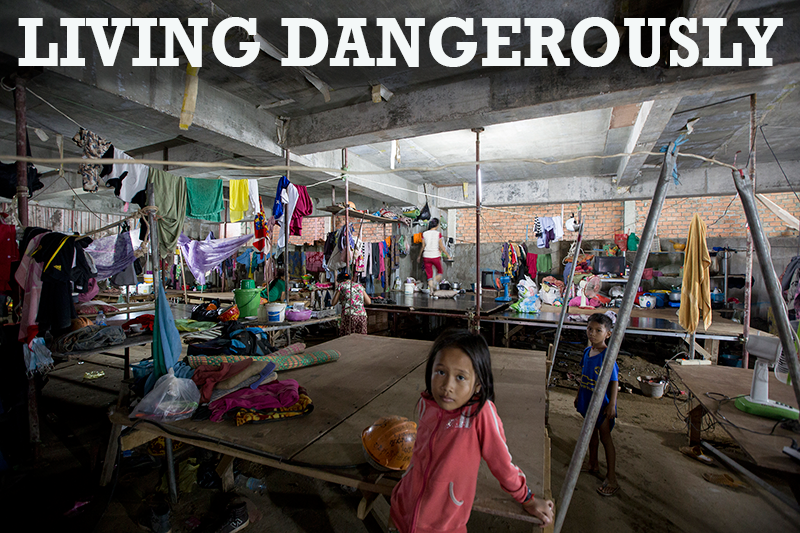

Two children stand in the basement of a construction site where they live, in Phnom Penh’s Boeung Keng Kang III commune in October. (Olivia Harlow/The Cambodia Daily)

Two children stand in the basement of a construction site where they live, in Phnom Penh’s Boeung Keng Kang III commune in October. (Olivia Harlow/The Cambodia Daily)Amid Phnom Penh’s building boom, construction sites double as homes for whole families.

At lunchtime one recent afternoon, Ros Srey Mao was relaxing with her 11-year-old daughter and several neighbors, watching a television soap opera while sprawled across one of the raised wooden platforms ubiquitous in Cambodian homes.

Pots and pans were piled nearby, and laundry had been laid out to dry on nearly every available surface. A chicken clucked somewhere out of sight.

It was a typical domestic scene, with one key difference: Ms. Srey Mao lives on an active construction site.

Along with a handful of other families, she, her husband and their daughter make their home in the basement of a half-finished apartment building that is slowly rising above the rooftops of Boeng Keng Kang III commune in Phnom Penh’s Chamkar Mon district.

Outside, a crane and a cement mixer were in full swing, creating a deafening roar that nearly drowned out the sound of the soap opera.

Originally from Kandal province, Ms. Srey Mao is one of Phnom Penh’s many itinerant construction workers who move from building site to building site, making about $5 per work day.

Her job is to assemble bamboo scaffolding, while her husband does heavier labor.

Lacking the money to rent a room in the capital, and without family or friends nearby, they often camp out at the sites.

Ms. Srey Mao said she didn’t mind the conditions herself, but she wished she didn’t have to bring her 11-year-old daughter with her.

“I brought her with me because I didn’t have a choice. I have no one to take care of her,” she said.

“I worry about her living here, of her getting sick, or stones or equipment falling on her.”

At another construction site in Daun Penh district, where a multistory karaoke parlor is rising from a street corner, 25-year-old Prum Monorea sat with her infant daughter. She has lived here with her husband for about a month.

While she doesn’t fear for the safety of her daughter, she is concerned about the giant pool of stagnant water in the basement of the site, teeming with rubbish and mosquitoes.

“I feel normal, like I’m in my home, and I am not worried about my daughter in terms of safety and security, but I am worried about her having health problems because there are a lot of mosquitoes here,” she said.

Clothes hang to dry at the construction site. (Olivia Harlow/The Cambodia Daily)

Clothes hang to dry at the construction site. (Olivia Harlow/The Cambodia Daily)The stories of these workers show a different side of Phnom Penh’s construction industry, which is close to becoming one of the largest sectors of the Cambodian economy, estimated to be worth about $3 billion dollars”with no obvious sign of slowing.

According to the latest report on Cambodia’s construction sector released by the Ministry of Land Management, Urban Planning and Construction, between 208,290 and 251,490 people are employed at construction sites across the country every day, between 96,500 and 108,500 of them in Phnom Penh.

However, there are currently no laws specifically covering construction-site safety, with the government leaving this responsibility to individual firms.

For Justin Landis, a project manager with the Bangkok-based construction management company ACH, who has worked on several projects in Cambodia, there are numerous problems with these makeshift camps.

“One of our goals is to raise the awareness of site provisions and health and safety environments,” he said.

“Getting rid of the labor camps is one of those ways, because it’s just not safe. Women, children, food, clothing, this type of stuff, it’s a fire hazard. People are cooking on site at nighttime,” he added.

“You bring the client to visit the project…and they see children walking around the site, it makes a terrible impression. And that directly affects us. Perception is everything.”

A worker eats lunch in the basement of the construction site. (Olivia Harlow/The Cambodia Daily)

According to Heng Sour, spokesman for the Ministry of Labor, existing labor regulations make it illegal for children to be on construction sites and stipulate that there should be separate areas for workers to live in.

“According to the law, we restrict underage work and there should be a separate living room, but it depends on the negotiations between the workers and the company,” he said.

Inadequate regulations, along with minimal enforcement of existing laws, affect many aspects of the construction industry, with deaths on building sites due to lack of safety regulations rising to roughly four people a day in 2009, according to the International Labor Organization, the most recent data available.

Mr. Landis said that for some developers, the expense of complying with labor regulations was so high that the possibility of a person dying on a construction site was worth the risk.

“When somebody dies, typically the payout is only about $2,500 dollars, so in terms of the contractor, that’s a risk they’re willing to take.

“If they lose a life and it costs them $2,500 for the funeral, that’s a small drop in the bucket for the construction cost. They can afford it,” he said.

Despite this, Mr. Sour says there are laws in place to punish developers whose construction practices cause injury or death.

“The law clearly states that if there is any misconduct and if it results in injury, the construction company needs to pay not only the compensation and the medical expenses, but also face criminal charges if they indirectly caused injury to the people,” he said.

A worker lies in a hammock. (Olivia Harlow/The Cambodia Daily)

A new law regulating construction is currently being drafted, and is expected to be finished later this year.Phuoeng Sophean, a secretary of state at the Land Management Ministry, said the law would at least attempt to eliminate some of the worst problems with on-site camps, including banning children from construction sites.

“But in the case of workers, it will depend on the actual situation of the construction site, and if they are allowed [to live there], the owners of the construction site will have to arrange proper accommodation for them with a good environment,” he said, adding that workers would not be allowed to live on small building sites.

Asked what legal actions would be taken if these rules were not followed, he said, “The law is still being drafted with hope to be finalized this year. So, I cannot answer this question.”

The transient lifestyle of many construction workers and their families affects women and children the most, according to Ee Sarom, executive director of Sahmakum Teang Tnaut, a local urban issues NGO.

“There is no proper hygiene, no clean running water or electricity, and there is a greater risk of violence, especially toward women who stay there,” he said. “Personal security is not so good.”

“Children cannot go to school because they cannot register at the local school. They need the documentation, and also because their families are mobile, they need to move to different places, so they cannot study.”

Indeed, sending their 11-year-old daughter to school is not even a remote possibility for Ms. Srey Mao and her husband.

There is nobody to take care of the child in their hometown in Prey Veng province, where they spend part of the year farming rice.

In Phnom Penh, they do not have a regular address and cannot afford the expense of books and school fees; most of the money they earn goes toward paying back a $1,000 microloan the family took out.

Instead, the child mostly hangs around the construction site, doing nothing.

“I cannot afford to send her to school,” Ms. Srey Mao said. “With the money I make, I don’t have enough to pay off the interest on my loan.”

At the Daun Penh site, Yoeun Narong, a 20-year-old construction worker who is also from Prey Veng, was hosting his 8-year-old sister, Lyhorng, on a visit during her school holiday.

“I think it’s safe for her because my manager instructed me and other workers not to allow children to go out of the construction site, but to take care of them inside, because inside, the construction material and steel cannot fall down,” he said.

As he spoke, Lyhorng sat next to him on the concrete floor, playing with pieces of rubble.

Asked how she liked living on the site, she said simply, “I feel afraid.”