When the International Labor Organization (ILO) released its annual world employment outlook last week, the data showed something remarkable—almost no one was jobless in Cambodia last year.

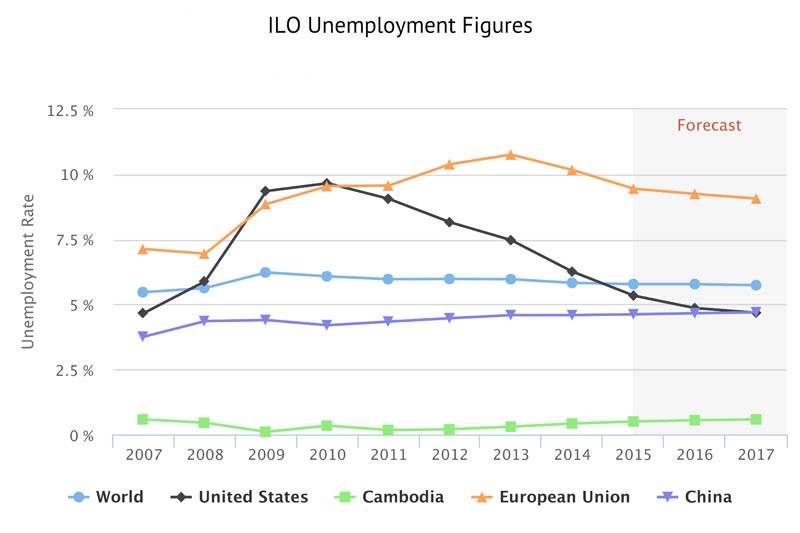

With unemployment at only 0.5 percent of the workforce in 2015, Cambodia had fared better than France (at 10.6 percent), the U.S. (5.3 percent), China (4.6 percent) and far better than the global average (5.8 percent).

In fact, of the 189 countries ranked by the ILO in 2015, Cambodia came in second only to Qatar (at 0.2 percent) in the race for the world’s lowest unemployment rate. Neighboring Thailand came third at 1.1 percent.

Not one to waste an opportunity to promote good news, Labor Minister Ith Sam Heng described the astonishingly low unemployment as “Cambodia’s pride,” according to state news outlet Agence Kampuchea Presse.

“Ith Samheng attributed this achievement to the Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC)’s efforts in improving work conditions and bettering people’s living standard,” read a report published on Wednesday.

“Besides, the RGC always pays attention to the promotion of investments in Cambodia in order to create work opportunities for people,” it said.

Yet beneath the impressive statistic lies a harsher reality of widespread near-unemployment, masked by the ILO’s methodology: Anyone who works just one hour a week is considered employed.

“The employed include people aged 15 and over who, during the reference week worked for one hour or more for pay, profit, commission or payment in kind, in a job or business or on a farm,” notes a 2013 ILO working paper on its methodology.

If such criteria was not inclusive enough, the paper added that those “who worked for one hour or more without pay in a family business or on a family farm” are also considered “employed” for statistical purposes.

The technique has long been the international norm for calculating unemployment in developed countries, where it has generated figures reflective of job market health. Yet it has produced numbers far less meaningful for countries in the developing world.

“That methodology is misleading because everybody has some kind of garden in the backyard, and if they go and grow some vegetables on their farmland, they will always be considered employed,” said Ou Virak, a trained economist who founded the Future Forum think tank.

“It’s a huge methodological problem also because if you are just helping your family in their mom-and-pop store by replacing your mom so she can go to the market, it doesn’t add much to employment,” he added.

“Helping out your family a few hours a day or week, you would never consider yourself as employed.”

Such a critique of the ILO’s unemployment calculation methods has not been limited to outside critics, with the body itself issuing reports debating how useful its methodologies are for developing countries.

A November 2007 paper issued by the ILO titled “Beyond the Employment/Unemployment Dichotomy: Measuring the Quality of Employment in Low Income Countries” asked how useful is its employment definition for emerging agrarian economies.

“The one-hour criterion…allows for short-time work, casual labour, stand-by work, and other forms of irregular employment that is common particularly in low-income economies,” the working paper said.

“However, being employed for at least one hour in a reference period is not necessarily indicative of gainful employment,” the paper noted. “Ready access to informal employment provides ample opportunity for people to be employed for at least one hour a day.

“In the large rural areas of most developing countries agricultural workers, especially in family enterprises, form the bulk of this unorganized sector,” it pointed out. “While such workers are not faced with a total lack of work, many are underemployed.”

The point was also acknowledged in last week’s report released by the ILO, which accompanied the global unemployment figures, and noted that “vulnerable” employment —such as working on one’s own farm or small family business—remained high in the region.

“Yet vulnerable employment remains comparatively high, especially in South-Eastern Asia and the Pacific and Southern Asia, where it reached 54.1 per cent and 73.6 per cent respectively in 2015,” reads the ILO’s outlook report, released on January 19.

“Countries with large informal sectors, such as Cambodia, Indonesia and Myanmar, continue to have high shares of vulnerable employment, in the order of 60 per cent, and there are no signs that they will decrease over the next couple years,” the report says.

Labor Ministry spokesman Heng Sour did not respond to requests for comment on Thursday about the applicability of the ILO’s figures to the employment situation in Cambodia.

However, ILO country director Maurizio Bussi said in an email that placing Cambodia’s unemployment rate at a mere 0.5 percent still accurately represented Cambodia’s overall situation.

“A short and confined reference period of 1 week, and a minimum of one working hour does tend to be seen as being too limiting to capture a situation of ‘lack of sufficient income earning opportunities,’” Mr. Bussi wrote in an email.

“However, in the Cambodia context, time-related underemployment (people working less than 40 hrs, willing & available to work more hrs) is also very low.”

Mr. Bussi said other gauges of unemployment, such as the Cambodian government’s own 2013 Intercensal Population Survey, have put unemployment figures only slightly higher, in ranges of between 2 to 3 percent.

He acknowledged that such figures were still low, but said the reason was that most people are en- gaged in whatever menial work they get. The larger issue, he said, was that the “earnings they get from this work is low.”

“It tends to reflect the fact that very few people can choose [afford] to be unemployed, and have to undertake any economic activities for survival. Unemployment rates in a context like Cambodia always have to be examined together with other labour market indicators,” he wrote.

“For example, unemployment rate tends to be remarkably low, but the employment-to-population ratios of men and women at around 80% in 2013…is quite high.”

The lack of opportunities in Cambodia’s job market, however, have proven one of the more exploitable issues for the political opposition over the past decade.

“On the part of the ILO, it is not only a joke to use such a definition of employment, it is an insult to those who are looking for a job,” opposition leader Sam Rainsy said by telephone on Thursday.

“Look at the hundreds of thousands of migrant workers who leave Cambodia. If Cambodia had full employment, with the fractional unemployment of 0.5 percent, why would so many Cambodians from all walks of life be going to Thailand to seek work?” he said.

“If most people had any alternative, they would not be doing the jobs they are doing. By using such a definition, the ILO encourages the government not to do anything, because they are so happy to say we have the lowest unemployment rates in the world.”