The country is set to embark on local elections that promise to highlight the economic hardships faced by many Cambodians despite a sustained annual growth rate and continued poverty reduction, economic and political observers said this week.

Today, the second day of this year’s World Economic Forum on Asean hosted by Cambodia for the first time, Prime Minister Hun Sen, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and other government officials, businesspeople and economists are expected to discuss the economic potential of Asean’s youth and technological advances, as well as how to promote growth that benefits more people.

A survey released by the Asia Foundation in February last year says just 8.7 percent of respondents reported having formal permanent work; 19.8 percent said their economic situations had deteriorated over the previous year; and 84.2 percent claimed that their households lived with material deprivation, whether moderate or severe.

Almost a third of Cambodians live with debt, and the poorest are historically indebted at a significantly higher rate—most commonly taking out loans so they can buy food, according to the Cambodia Socio-Economic Survey, carried out by the Planning Ministry’s National Institute of Statistics.

The Asia Foundation survey also reports optimism among the majority, however, who have experienced improved livelihoods and bear hopes for upward mobility.

Cambodia is still a poor country, but there’s been progress compared to a decade ago, said Arup Raha, group chief economist at Malaysia-based bank CIMB.

“Growth rates have been good and…growth is a basic requirement to get out of poverty,” Mr. Raha said. Avoiding economic shocks that typically hit the poor harder, diversifying the nation’s production base and continuing to invest in health, education, infrastructure and the better delivery of public services would help more people escape from poverty, he said.

“The good news for Cambodia is that they are in the early stages of development, which means they can have sustained growth rates for many years if they get the policy mix right,” Mr. Raha said. “They are on the right track.”

While people’s quality of life has generally improved in recent history, social mobility has occurred at different paces, political analyst Lao Mong Hay said.

“The feeling of inequality seems to be a general concern of many people,” Mr. Mong Hay said. “Inequality of material well-being, that is a factor to me in the choice of party.”

Those who have wealth and power and are benefiting from the political status quo will continue to vote for the ruling CPP, whereas the rest will vote against the ruling party, he said.

“Rural poverty remains widespread, and the gains that have been made nationwide are reversible as a large number of people still find themselves just above the poverty line,” said Miguel Chanco, lead Asean analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU).

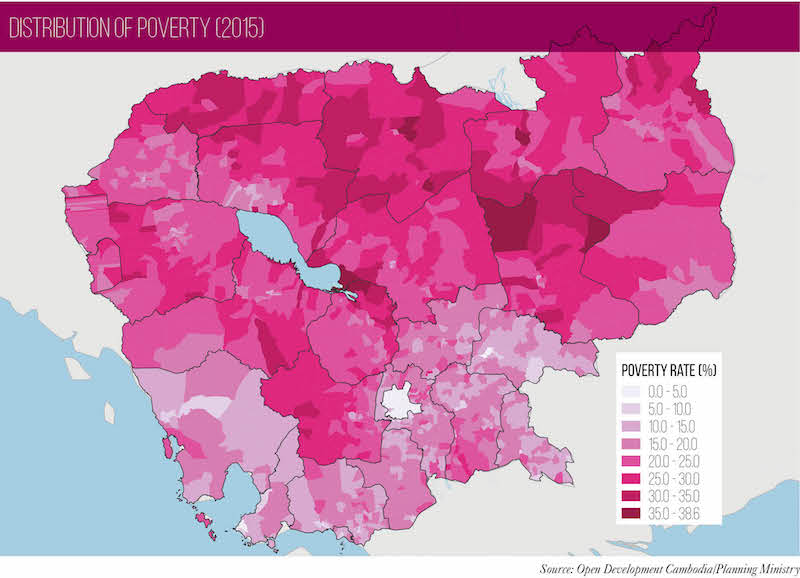

According to data from the Planning Ministry, poverty rates across the country range from almost zero—particularly around Phnom Penh—to as high as 38 percent in some rural communes, as of 2015.

Meanwhile, the average size of household debt has inched up to about 4 million riel, or about $1,000, according to a National Institute of Statistics report.

For many Cambodians, the most pressing economic hardship they face is “the monthly payment they have to make to microfinance institutions,” said Ou Virak, political analyst and head of public policy think tank Future Forum.

“If you solve [indebtedness], you’re going to get a lot of votes,” Mr. Virak said.

The government launched a weekslong publicity campaign in February with the stated aim of clarifying that loans from microfinance institutions (MFIs) were private, not state loans.

While commune councilors and village chiefs have in the past acted as witnesses to certify microfinance loans—“with the implicit message being that these contracts are official and will be enforced by the local government”—indebtedness among loan takers may make local officials less likely to facilitate loans for their constituents, fearing they will be blamed for voters’ debt, he said.

“That’s the concern for the ruling party, because that could be [thought of as being] synonymous with the local authorities…[that the party] has something to do with the actual loan itself,” Mr. Virak said. “I think that’s why the CPP felt it was important to make that clarification.”

“These things will be issues in the local elections because they’re very tangible and direct in the lives of people,” he added.

A report from Future Forum released on Tuesday says the economy is likely to play a major role in upcoming elections.

Three socioeconomic trends may be affecting voting habits: a workforce shifting from agriculture to the industrial and service sectors, rising household incomes, and borrowers increasingly going to formal lenders, like MFIs, for loans, rather than their family, the report says.

“People are now increasing[ly] relating their needs to the political program, which is evident by a willingness to vote for parties that prioritize economics and infrastructure in their communities,” it says. “People nowadays evaluate a political party based on their families’ current economic status.”

But with rural road networks expanding and wages for government employees, the military and garment workers rising, CPP spokesman Suos Yara said it was becoming difficult to identify money problems affecting citizens’ lives.

“The CPP does not worry that economic hardship, if any, would affect the outcomes of upcoming commune council election[s]…because the majority of Cambodians are enjoying greater prosperity than they have ever experienced,” Mr. Yara said.

While touting Cambodia’s successes since the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime, Mr. Yara said the government still had goals, including further reducing the poverty rate “to as low as possible.”

“To do that, we need to increase our skilled labors to attract more foreign direct investment, create more jobs inside the country and industrialize agricultural production,” he said.

The political discourse in recent years has focused on the CPP’s persecution of the CNRP, but the opposition will need to do more, including proposing credible ways to advance livelihoods, in order to gain public support, Mr. Chanco of the EIU said.

On June 4, when ballots are scheduled to be cast, “Cambodians will be voting with their pocketbooks—that is, for the party they believe will provide them with the best chance to climb the economic ladder,” he said.

Kem Monovithya, the CNRP’s deputy public affairs director, said Cambodia was “a country full of a young, potential labor force, who are without decent-paying jobs to make ends meet.” Job creation would require institutional changes that the current government has been unable to accomplish for decades, she said.

“We need to invest significantly more than today in our education system to prepare our labor force for the better and right kind of jobs,” Ms. Monovithya said.

“Living costs are skyrocketing; current employment opportunities and wages do not match that,” she said.

Inflation was an estimated 3.5 percent last year, and is forecast to rise this year and the next two, reaching a projected 5.2 percent by 2019, according to the World Bank.

Miguel Eduardo Sanchez Martin, senior economist at the Bank’s country office, said a “sluggish” agricultural sector in recent years could affect Cambodia’s success in poverty reduction attained over the past decade.

While production picked up last year due to favorable weather conditions, “agricultural commodity prices remain depressed, limiting growth in total agricultural exports, which affects the livelihood of millions of Cambodians in rural areas,” Mr. Sanchez Martin said, citing the drop in price of rice, rubber and cassava in recent years.

On a positive note, he said, “rural households have increasingly diversified their livelihoods, tapping into both the rural off-farm economy and remittances to help sustain poverty reduction.”

Yang Saing Koma, co-founder of the Grassroots Democracy Party, said that despite the majority of the population living outside cities and an economy that is still agriculture-based, Cambodia’s competitive edge in the sector compared to neighboring countries was weak.

Many farmers were leaving their villages, seeking jobs in other countries to pay their debts and earn higher wages, especially in Vietnam and Thailand, Mr. Saing Koma said.

“We export the labor, but we import the products,” he said, citing processed foods, fertilizer, seed, fruits, vegetables and animals imported from abroad.

“This can drain income for our country,” he added.

Mr. Virak, of the Future Forum, said understanding voters’ perceptions of their financial woes and potential for social mobility could help predict who will come out on top in the upcoming commune elections.

If the general outlook is positive, the CPP will have the advantage, he said. But if more voters are frustrated by their economic situation, and have greater expectations that local officials should address local problems through policy solutions, the CNRP could benefit.

“If you know that level, you can do a better prediction of the outcome of the election,” he said.

(Additional reporting by Hang Sokunthea)

Correction: An earlier version of this article said the Asia Foundation survey was released in 2015.