(Un)protected Areas

Private companies are clear-cutting the Beng Per Wildlife Sanctuary’s forests and replacing them with rubber plantations. (Zsombor Peter/The Cambodia Daily)

(Un)protected Areas

In Cambodia’s wildlife sanctuaries, conservation areas and national parks, forests are falling as fast as anywhere else

A recently cleared field inside the ELC of the Sovannaphum Viniyok Kase-Usahakam company, connected to businessman An Mady, in the Beng Per Wildlife Sanctuary in Preah Vihear province (Zsombor Peter/The Cambodia Daily)

ROVIENG DISTRICT, Preah Vihear Province – Preah Kay sped easily over the rutted dirt path winding through the thick brush of the forest, whipping his beat-up Honda Dream around muddy puddles like a motocross driver and ducking under head-high branches.

It was midday and sunny, but the canopy was keeping everything in the shade. After a rough 20 minute ride off of Road 62, Mr. Kay rattled to an abrupt stop and stepped off. Behind him was the forest. In front stretched thousands of hectares of freshly clear-cut land, stripped to the sunbaked dirt of nearly every root and stump. About half a kilometer away, a two-story blaze was burning away what was left.

All of it—the forest, the field, the fire—was in the heart of the Beng Per Wildlife Sanctuary, one of 32 protected areas that together cover more than a quarter of the country’s surface.

The Environment Ministry, which manages 23 of those areas, including Beng Per, says the forests given over to the rubber plantations cutting them down are degraded, stripped of their public value long ago by poachers and illegal loggers. But Mr. Kay, an ethnic Kuy villager whose ancestors have been living off these forests for generations, said the ministry’s claim wasn’t true until the rubber plantations started arriving over the past few years.

“The government is wrong; it is still healthy forest,” he told reporters during a visit to the sanctuary in late June. “But the government doesn’t come here to see it with its own eyes. They lie because they want the trees.”

A growing body of evidence backs him up. New data on forest fires show that the economic land concessions (ELCs) the government has been handing out for rubber plantations and other large-scale agri-business ventures are targeting the country’s best forests. The latest U.S. satellite data also show that those forests are falling inside Cambodia’s protected areas as fast as they are nationwide.

In 2014, the University of Maryland, using U.S. satellite imagery, released what it called the most comprehensive and high-resolution set of data on global deforestation from 2000 through 2012. According to its figures, Cambodia experienced one of the fastest rates of forest loss in the world over the period.

Updated data the university released earlier this year for 2013 showed the pace of deforestation picking up.

According to local rights group Licadho, which crunched the university’s raw numbers, Cambodia lost 14.6 percent of its 107,000 square km of forest cover between 2000 and 2013, an average of roughly 1.1 percent per year. In 2013 alone, the country’s forest cover shrank by 2.3 percent.

The Environment Ministry’s protected areas did about the same. They lost 12.2 percent of their forest cover since 2000 and 2.2 percent in 2013 alone.

In other words, a mature tree standing anywhere in Cambodia had nearly no better chance of surviving those 13 years for having grown inside one of the Environment Ministry’s protected areas.

“It shows that the protected area system, as it is implemented now, is simply not working,” said Marcus Hardtke, who has worked with a number of groups on forest and conservation issues in Cambodia since the mid-1990s.

“The protected area system is at a crisis point, not only individual areas but the very idea of what declaring a protected area actually means,” he said. “At the moment, the average Cambodian can’t see the difference between a protected area and every other place…not when the Ministry of Environment itself engages in large scale habitat destruction. No constructive land management is possible under these circumstances.”

In 2013, none of the country’s protected areas fared worse than Beng Per. The wildlife sanctuary lost 12.4 percent of its forest cover that year, about 209 square km. It has lost 721 square km of forest cover since 2000, about 33 percent. A few other protected areas have lost more forest cover as a share of what they started out with. The Snuol Wildlife Sanctuary, in Kratie province, has lost 59 percent of the forest it had in 2000. But none has lost more actual forest than Beng Per.

The wildlife sanctuary, just north of Cambodia’s dead center, is a microcosm of everything that has gone wrong with the country’s protected areas.

Settlers and illegal loggers have been picking off parts of Beng Per’s forests for decades, poaching much of the area’s rare and endangered wildlife along the way. The U.K. environmental rights group Global Witness found patches of clear-cutting as early as 2001.

But none of it compared with the deforestation that has followed the Environment Ministry’s approval of nine ELCs in the sanctuary, all for rubber plantations, in 2010 and 2011.

The Kuy community in and around the sanctuary’s O’ Por village is sandwiched between two of the biggest: timber magnate Try Pheap’s rubber plantation to the east, and another tied to fellow business mogul An Mady to the west. In the middle, the Kuy have been left a thin strip of government-approved community forest along either side of Road 62, a two-lane strip of asphalt that runs through the heart of the protected area.

On his 100-square-km concession, Mr. Pheap has already cleared nearly everything. Behind a guarded four-story gate, the tallest things in the village, young rubber trees stretched to the horizon, still a few years off from tapping. Across the road, Mr. Mady has cleared nearly half of his concession of about the same size, and is working on cutting down the rest.

“Before An Mady and Try Pheap came to grow rubber, it was full of healthy forest: Kra Koh, Phdiek, Chheuteal, Po pel, Koki, Beng, Kra Nhung, Thnong,” Mr. Kay said, rattling off the names of some of the rarest, most prized—and legally protected—tree species in the country.

He said that most of the best trees had now been logged out, both inside and outside the plantations, including the old resin trees the Kuy tap for a living.

Kuy Soeung, 70, another local Kuy, said the forests of his youth were teeming with wildlife. Herds of elephants would pass through, though the Kuy say the Khmer Rouge killed off the last of them here in the 1970s.

Breaking off westward from Prey Lang, the largest remaining lowland evergreen forest in mainland Southeast Asia, Beng Per has been home to some of the country’s rarest animals, including the endangered pileated gibbon and fishing cat. The Kuy say it still was until recently, along with wild deer and pigs and water birds. They say the Khmer Rouge and illegal loggers did their damage, but at least left most of the trees here standing.

“But after the companies took the land for their rubber plantations, the trees have gone away,” Mr. Soeung said. “Before, everything was good. Now, the wildlife has disappeared, too. We used to see the monkeys in the forest, but they don’t have any more shelter.”

“The only thing left of Beng Per is the name,” he said. “The forest is gone.”

Like much of Cambodia’s bureaucracy, the country’s protected-area system is a child of its colonial past.

By the end of their century-long rule, the French had turned about 20,000 square km into wildlife reserves and roughly twice as much into forest reserves, using one for hunting and the other for logging. With independence in 1953, the Cambodian government took control of the wildlife reserves. The Khmer Rouge did away with them in the 1970s, and they stayed forgotten for the next decade.

It was not until the U.N. arrived in the 1990s that the protected areas returned. Working off what the French had done, a team of conservationists added the lowland evergreen forests the colonialists had largely ignored, and turned what had been 20,000 square km into 33,000. In 1993, the same year that democratic elections returned to Cambodia, King Norodom Sihanouk signed off on a royal decree creating 23 protected areas for the Ministry of Environment. The Ministry of Agriculture eventually took on nine others.

The laws on exactly how to protect them all came later.

A Land Law arrived in 2001, a Forestry Law in 2002, a sub-decree on ELCs in 2005, and finally a Protected Areas Law in 2008. Together, they require that every ELC application come with an environmental impact assessment (EIA), that local communities be consulted, and that no one own more than 100 square km worth of ELCs nationwide. They say that protected areas have to be zoned into “core” areas to be spared at all costs, “conservation” areas be developed only sparingly, and “sustainable use” areas that may be leased to investors, but even then only for the good of the local community.

Through the 1990s, logging concessions stayed out of the protected areas until the government put an end to those operations in 2001, sparing the areas the worst of the decade’s deforestation. A few ELCs started appearing in the protected areas 2008 and 2009. But of the 113 ELCs the Environment Ministry approved inside its protected areas as of 2012, when the government put a hold on granting new ones, almost all of them arrived in 2010 and afterward, just as the deforestation was picking up, and years after the laws meant to protect those areas were in place.

The Environment Ministry admits the laws have been flouted.

Seven years after the Protected Areas Law took effect, not one of the ministry’s 23 areas has been zoned. In 2012, a ministry official conceded that only one in 20 approved projects had carried out an environmental impact assessment (EIA). In an interview last month, ministry spokesman Sao Sopheap said many of the ELCs still had not done an assessment.

“Of course we haven’t done up to the requirement yet,” said Mr. Sopheap, the environment minister’s cabinet chief. “We have to acknowledge that a number of economic land concessions still need to do an EIA.”

Mr. Sopheap said he could not explain why the ministry had for years been giving out concessions to companies that had not conducted impact assessments.

“This is the history,” he said. “I have only this for you right now.”

As for why not one of its protected areas had been zoned in the past seven years, he said the process was “a heavy task” that a number of conservation groups were now helping with.

Even without the zoning and impact assessments, Mr. Sopheap said the concessions were still somehow managing to avoid the protected areas’ core zones. He said a team of technocrats at the ministry had done “rapid assessments” of each project, but he had no authority to share them and did not know who did.

Mr. Sopheap said he could not provide a full account of which ELCs had impact assessments done, either, because the ministry’s review was still in progress. But he said that Mr. Pheap’s concession in Beng Per was one that had not.

And those are just the laws the government admits were broken.

Across the country, villagers and rights groups have accused ELCs of laundering vast quantities of timber, using their concessions to pass off wood that has been illegally harvested outside their borders as their own. No one in Cambodia has been assailed by those claims more than Mr. Pheap himself.

The timber magnate has been accused of using his connections to the first family—he was briefly an official advisor to Prime Minister Hun Sen—to secure the exclusive right to buy up all the wood harvested on every ELC in Ratanakkiri province, where he had two concessions of his own until recently giving them up. He has reportedly struck similar deals elsewhere, though his staff admit to having no checks in place to judge the provenance of the wood they are buying.

Mr. Pheap’s many companies have been accused of doing much of the illegal logging themselves. In February, Global Witness released the results of a months-long undercover investigation during which their researchers tracked loggers illegally looting Ratanakkiri’s Virachey National Park—another of the Environment Ministry’s properties—of its best trees and moving them to Mr. Pheap’s sawmills and depots in the province, then shipping them abroad. In 2013, Cambodia Daily reporters also met illegal loggers in the park who said they were working for Mr. Pheap.

In 2012, Fauna and Flora International prepared a report that was never published accusing Mr. Pheap of using his rights to log the reservoir for the planned hydropower dam inside Pursat province’s Phnom Samkos Wildlife Sanctuary—yet another Environment Ministry property—to launder thousands of cubic meters of protected Kra Nhung, or rosewood, worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

The accusations have followed Mr. Pheap to Beng Per.

The Kuy say Mr. Pheap’s plantation workers have been poaching rosewood and other protected trees inside the sanctuary, but outside the company’s concession, since they arrived.

“I asked them who they were, and they said they worked for the company,” said one villager, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was facing incitement charges he believed were brought against him as a result of his protests against the logging.

“They use the company’s trucks, and they transport the trees to the company,” he said.

Mr. Pheap’s concession has been stripped almost completely bare since 2013. But next to his sawmill was a large pile of first-grade Koki that, the villagers said, was not there a few weeks ago.

Mr. Soeung said workers from Mr. Mady’s plantation have been at it, too.

“We have seen the companies logging outside their concessions. They take the wood onto their plantations, and then they ship it out,” he said. “The authorities know. We have told them, but they ignore us…. They protect the companies.”

They have reason to think so.

Both Mr. Mady and Mr. Pheap hold the title of oknha, an honorific secured with a minimum $100,000 donation to the state. In 2011, a few months after receiving his Beng Per ELC, Mr. Pheap went one better. He donated $30,000 to the prime minister’s ruling party, the CPP, to build a head office in Rovieng district. At the same time, he donated $100,000 to the Environment Ministry to build a ranger station for the sanctuary.

The station sits directly across the road from the towering gate at the entrance of Mr. Pheap’s rubber plantation. At the right time of day, it literally sits in the gate’s shadow, and it’s hard to see where the $100,000 went. A simple six-foot wall runs around a pair of basic, low-slung buildings.

Inside, watching television, was the station’s director, Huy Sokun. He said his 15 rangers patrol the district’s share of the sanctuary on a daily basis.

“There are still some animals, but not many,” he said.

But as the conversation turned to sensitive topics—how does he protect a sanctuary being stripped of its forests?—Mr. Sokun grew quiet.

“I don’t dare to answer your questions,” he said. “I will get in trouble if I give the wrong answer.”

Mr. Mady declined to speak with a reporter when contacted for this story. Deth Seila, who runs Mr. Pheap’s Beng Per plantation, denied the allegations of illegal logging.

Mr. Pheap himself visited the plantation two weeks ago for its official opening. Standing by his side for the ribbon-cutting ceremony was a beaming Say Sam Al, the minister of environment.

Mr. Sam Al, who took control of the ministry after the 2013 national election, ignored numerous request for an interview over the past three months.

But on the sidelines of an event in Phnom Penh to launch a new initiative to protect Virachey Park, in March, he insisted that all the forests the ministry had been leasing out to concessionaires were already degraded, often before the protected areas were even revived in 1993.

“You have to understand [the] Cambodian context,” he said. “When we drew up 23 protected areas, some of those, a lot of those areas [were] occupied by people, by villages…. We thought there was forest there, but there is not a jungle there any more. That’s why we give out this concession land. We actually assess that. If there’s a jungle there, we don’t give it out.

“See, that’s our problem. Some of them [were] cleared by people. Look, wood is part of our culture. People build houses from wood, they still need wood for fuel consumption. All sorts of problems.”

Mr. Sam Al blamed some of the criticism Cambodia has endured for the way it has treated its forests on a faulty Western mindset.

“If you use the mindset from the Western world, it’s not gonna happen,” he said. “The forest is not there anymore when we give it out, you understand. When we drew that [the protected areas] out, some of the places that we drew, we didn’t even go there, we [hadn’t] even been there. It was dominated by Khmer Rouge at that time…. So it’s complicated.”

The Kuy in Beng Per say their forests were healthy until the ministry started giving them away to the rubber companies. The Environment Ministry’s own reports agree with them.

A joint study the ministry prepared with the World Wide Fund for Nature in 2004 on Cambodia’s protected areas said there were still “exemplary plant communities” inside Beng Per, covering the very same areas the ministry has given the rubber plantations. The study found “exemplary” riparian areas and animal communities in the sanctuary, too.

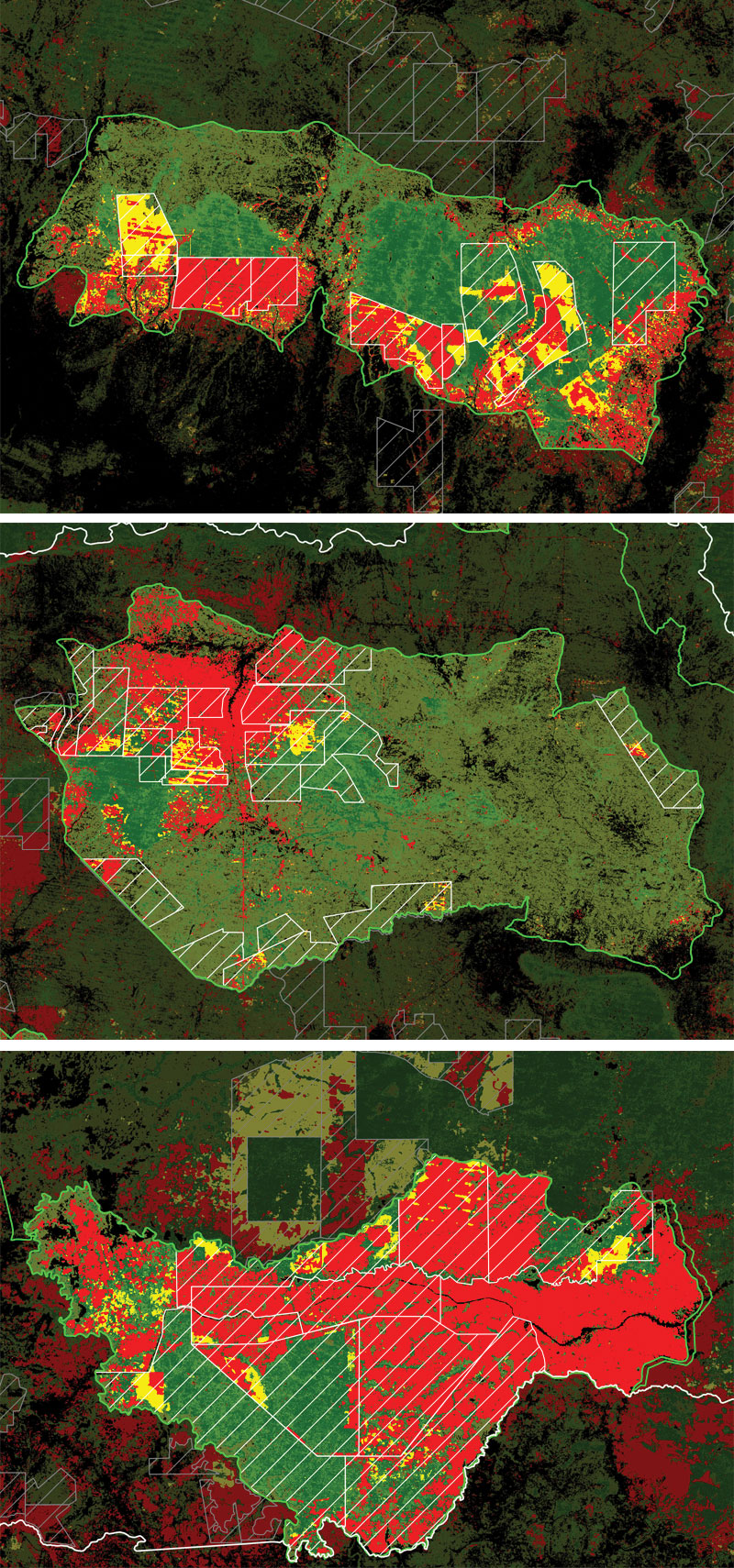

Recent satellite data collected by NASA measuring carbon emissions from forest fires also show that the ELCs the government has given out overlap with some of the best, least degraded forests the country has—or had.

In a report it released last week, U.S. environmental protection group Forest Trends says it analyzed NASA’s forest-fire data for Cambodia during the 2012-2013 dry season. More carbon emissions generally mean more biomass. More biomass means a healthier forest. It says emissions from evergreen forests being cut down inside ELCs were almost 10 times higher than emissions from outside the concessions, “confirming that corporations are targeting the oldest and most valuable forests, many of them on national forest lands, for logging.”

Forest Trends also looked at fires in a few protected areas and found “medium” levels of emissions in Beng Per, the Kulen Promtep Wildlife Sanctuary and the Seima Biodiversity Conservation Area, confirming “that they retained substantial biomass.”

“Forest fire data in the report directly contradicts the claim that forest being cleared in ELCs is not worth conserving or restoring,” said Kerstin Canby, who leads the group’s forest trade and finance program.

“Forest conditions vary greatly where ELCs are being allocated. Some are degraded, others are disturbed but recoverable, and some are virtually pristine…. The data illustrates that ELCs are the major form of encroachment into remaining areas of good forest.”

The group says its data also adds weight to long-running complaints that the government has been letting companies use their ELCs, meant almost exclusively for growing crops, as if they were the logging concessions it officially did away with in 2001, turning a quick profit on the timber and getting out. Ms. Canby said this had made the the country’s protected areas especially attractive.

ELC leases go for a few dollars per hectare. One cubic meter of some of the best timber can earn thousands. At those rates, a prime concession can quickly pay for itself and more.

“The extent of valuable, dense evergreen forest is disproportionately high in those concessions that are located within protected areas. This [data] challenges the assertion that activities in ELCs are genuinely focused on agriculture rather than on harvesting some of Cambodia’s last remaining high-value timber,” she said.

“It appears that many actors are deliberately exploiting the weak implementation of the Protected Area law to acquire ELCs on valuable forest land in order to profit from the clearance of timber, with or without ultimate intentions to deliver on agricultural development commitments.”

Licadho and other rights groups that monitor the ELCs say many have failed to follow through on their contracts. The government admits it’s been a problem.

The Environment Ministry’s other main defense for turning vast stretches of protected areas over to rubber companies is economic: As a poor, developing country, Cambodia needs jobs and industry.

“We give out economic land concessions hoping to build our economy,” Mr. Sam Al said in March. “As a nation, we need to do whatever we can to build a strong nation, and also to create jobs for our people. That’s our main goal.”

He said the ministry wants to move villagers out of the forest.

“What we’re trying to do is develop our agro-industry, to create jobs for our people so hopefully they don’t depend on the forest any more, they depend on something else, on skills,” he said.

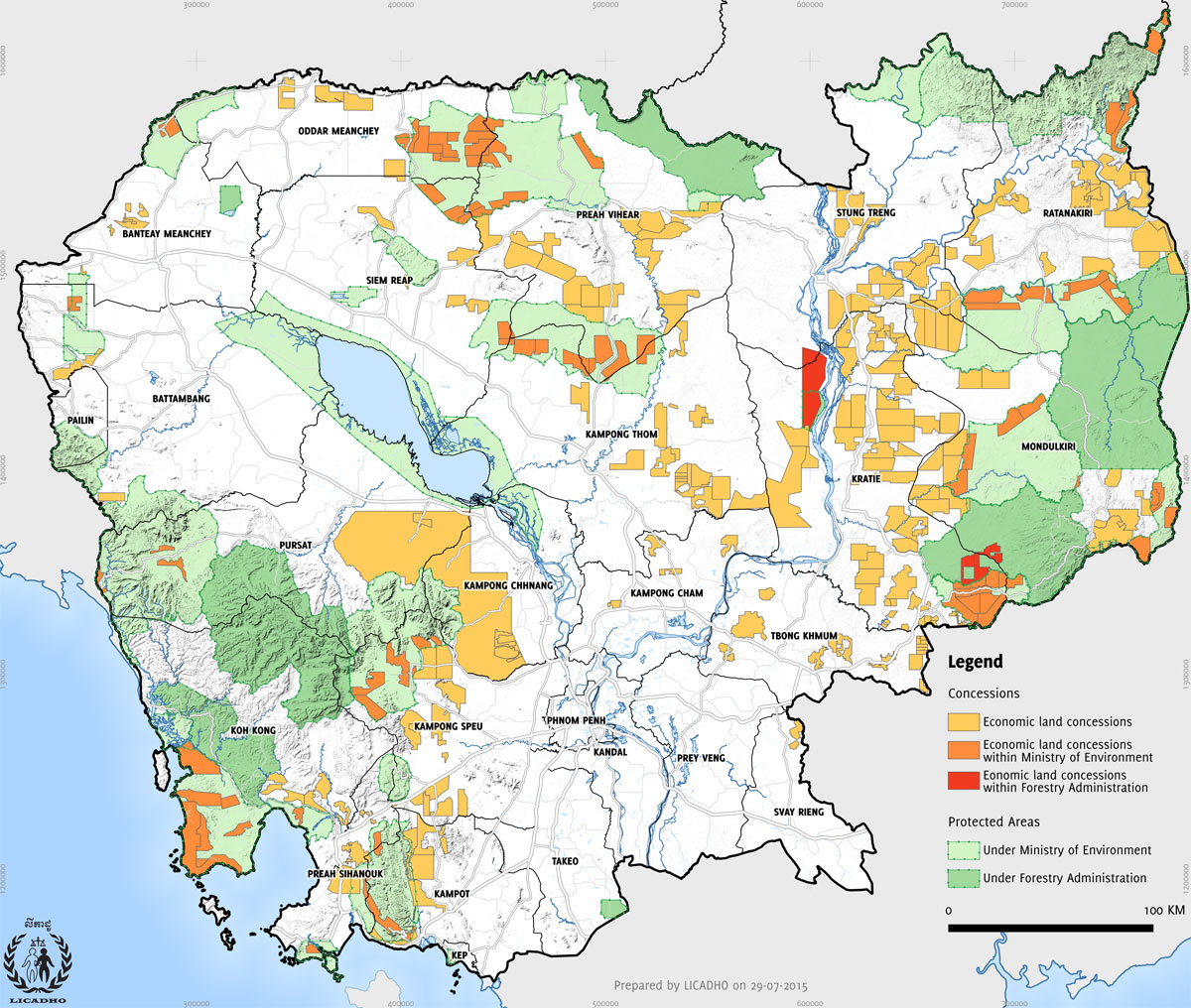

Neither the environment nor agriculture ministry maintains an up-to-date public list of its ELCs. The Environment Ministry says they oversaw about 143 between them when Mr. Hun Sen put a hold on the granting of new concessions three years ago.

Licadho, which tracks public records on ELCs and does its own field research, says the ministries currently oversee a combined 270 concessions, covering more than 21,000 square km. Of the 77 ELCs in protected areas, Licadho says, all but four are managed by the Ministry of Environment.

The ministry says those ELCs are pulling the rural communities around them out of poverty. It has no evidence to back up the claim, however, and every new study says otherwise.

Rights groups have accused ELCs inside and outside of protected areas of stealing land off of hundreds of thousands of local farmers over the past 15 years, driving many of them out of their homes with little or no compensation.

In 2012, the Mekong Institute, a regional inter-governmental group that includes Cambodia, surveyed 188 indigenous residents of six villages next to ELCs. More than half of them said they had lost land to the concessions. Three in four said they turned down the jobs the companies offered, or quit, because the wages were too low, because they felt cheated, or were angry with the firms for having taken their farms. More than nine in 10 said the ELCs had done nothing good for them.

The journal Land Use Policy published a similar study last month. Led by the University of Copenhagen, the researchers surveyed more villagers—600 people in 15 villagers across three provinces—but did most of their field work in 2008 and 2010.

“ELCs were found to consistently have negative impacts on household total income, environmental income, size of available cultivable land and livestock holdings. The total household annual incomes…were estimated to decrease by 15 [to] 19 percent,” the researchers said. “While providing some employment opportunities, we find no evidence of positive income effects of ELCs on households in the areas where ELCs are located.”

In Beng Per, the Kuy say they used to farm for half the year and live off the forest for the rest. They say the rubber plantations have forced them to turn to farming year round and that they are worse off for it. Most of the jobs on the plantations, they say, have gone to outsiders.

“We have lost our lakes, we have lost our jobs. There are no animals to trap, there is no forest,” said Sok Chhit. “If the minorities use the forest, it is good for 17 lives. But the company uses it and it’s all gone.”

Cambodia’s Kuy communities are spread across the whole of Preah Vihear, from Beng Per in the south to the border with Laos and Thailand. They have their own language. Like most of the country’s indigenous communities, they believe in spirit forests and have practiced rotational farming for generations, relying on their forests for the rest.

Mr. Chhit, a tall, heavy man with a sharp stare, grew agitated as he spoke, brushing off his wife’s pleas to calm down.

“They stop the villagers from collecting things from the forest. When we do something, they tell us to stop, they say we need to ask for permission,” he said. “The companies just want us to starve. If the government keeps ignoring us, we will be gone by 2020. The government just wants to kill the Kuy. The government wants to kills the people. The forest cannot grow because they kill the roots.”

In place of those roots, most of the plantations taking over are planting rubber.

Of the 270 ELCs on Licadho’s list, 151 were granted to grow rubber trees or a combination of rubber and other crops, together covering more than 9,300 square km. The share of ELCs going to rubber plantations inside the country’s protected areas is higher still.

In a speech two years ago, the prime minister laid out his vision of turning rubber into Cambodia’s next big crop, to be second only to rice. In the next five years, he said, the plantations would put more than 1 million people to work and export 1 million tons of rubber (The country exported 98,000 tons in 2014).

At the time, Mr. Hun Sen said his plan struck the perfect balance between development and conservation, noting that roughly half the country was still covered in forest.

“This shows that the government balances the need to create jobs for poverty reduction and the need to protect the environment due to the fact that rubber trees are considered part of the forest coverage,” he said.

But researchers and conservationists say rubber plantations cannot compare with healthy, natural forests.

In April, researchers at the University of East Anglia in the U.K. published the first review of other studies done on the impacts rubber plantations were having on biodiversity in Cambodia and around the region. Their paper said the plantations were proving “catastrophic” for the area’s endangered species.

Lead researcher Eleanor Warren-Thomas said they were a “disaster” for protected areas.

“We show in our paper that rubber plantations hold very little value for biodiversity relative to natural forest,” she said. “Clearing of natural forest for conversion to large scale, monoculture rubber, particularly in protected areas that are already known to have exceptional biodiversity value, is a disaster for biodiversity.

“There’s already data showing that birds, bats and beetles suffer in rubber plantations, and it’s extremely unlikely that Cambodia’s amazing mammal species, like gibbons, banteng and elephants, could ever persist in the monoculture landscapes of rubber that are springing up around the country,” she said. “Cambodia has globally unique species and forest ecosystems that exist nowhere else on the planet on the same scale; converting these to rubber is a huge loss.”

Mr. Hardtke, the conservationist, agreed.

“Monoculture plantations are not forest,” he said. “Apart from parking lots, nothing could be more contradictory to biodiversity and wildlife conservation. The idea that, for example, rubber plantations could be considered ‘wildlife sanctuaries’ is preposterous.”

Even financially, the plantations might not be the country’s best bet.

In 2011, researchers in Cambodia studied the economics of growing a variety of crops in various ways. They considered rubber, cassava and cashew grown by smallholders versus agribusiness operations, and whether they cut down forests to grow them. Clearing natural forests to grow rubber at an industrial scale, they concluded, was just about the worst option.

Mr. Sopheap, the environment ministry spokesman, was apologetic for the ministry’s many failings in handling its ELCs, contrite even.

“Aside from the EIAs, we have so many problems in relation to the ELCs. That’s why the government decided to issue Directive 01,” he said, citing Mr. Hun Sen’s 2012 order for a full legal review of all the ELCs in operation, at the same time he put a hold on new ones.

“That’s why we have to clean up the ELCs,” he said. “We start by cleaning up.”

Since the order, the ministry says it has canceled 23 of its 113 concessions and shrunken four. It says another four firms returned their concessions voluntarily.

But rights groups have doubted the government’s commitment to genuine reform from the ELC review’s start.

In the months after Mr. Hun Sen put a hold on new ELCs, the government approved 32 more, most of them inside the Environment Ministry’s protected area. Officials said the applications had been in the pipeline before the premier’s order came down.

The ministry has offered a list of the mistakes committed by the ELCs it has canceled. But it won’t say which ELCs made which mistakes.

Rights groups also say that most of the ELCs it has canceled were already abandoned by the companies that leased them and that the ministry won’t touch the ones their owners still want, especially if the owners are well connected.

That seems to go for Mr. Pheap and his rubber plantation in Beng Per. The Environment Ministry’s Mr. Sopheap said he would get to keep his concession, but would still have to conduct an environmental impact assessment, even though he has already cut down nearly every tree that was there. The spokesman said the assessment could still prove useful in protecting the area’s rivers and streams, and could be used to help compensate the community for any damage done.

“There is the impression that recent ELC cancellations are more of a book cleaning exercies than a change in policy towards conservation goals. Very little has changed on the ground,” Mr. Hardtke said. “I don’t know how much decision making power the new minister actually has, but so far the review looks a lot like window dressing. A serious review has to start with a logging moratorium in all ELCs, for example.”

As for the protected areas, he said the whole system needed an overhaul.

“What is needed now is a restructuring of the system,” he said. “Boundaries need to be adjusted, some areas have to be given up because they are converted on a large scale already, like Snuol. This is hard for the ministry, as control over land is a pillar of its income…. Other areas urgently need official protection status and need to be included in the [protected area] system.”

Other conservationists in Cambodia also suggest redrawing the boundaries of the ministry’s protected areas, abandoning what can no longer be saved and committing to what can.

“Cambodia’s pretending it’s going to protect 26 percent of its land. Well, it can’t…. So let’s be sensible and honest about this,” said one long-time conservation worker in the country, who asked not to be named because of his ongoing collaboration with the government.

Snuol, he said, was lost.

“So why have a ranger station there and pretend it’s being protected? Let’s find the 12 percent we really want to protect, and let’s protect that,” he said.

Letting companies develop the edges of protected areas and using the revenue to save the core, the way the Protected Area Law is meant to work, was still a good idea, he said.

“That’s a great idea, because how else are they going to make money? It’s just been done badly,” he said. “The problem is, there’s a lot of shady people behind it.”

Legally, all the money the Environment Ministry’s protected areas earn in fees and taxes goes straight into the national coffers. But in a country as corrupt as Cambodia, bribery is blamed for much of what has gone wrong with the ELCs, and why it will be hard to change.

Some conservationists are warily optimistic that Mr. Sam Al may just manage to steer his ministry onto the right course. But his presence at Mr. Pheap’s side during the inauguration of the timber magnate’s Beng Per rubber plantation last month has also soured some moods. They all agree that the fate of Cambodia’s protected areas ultimately rests with the people above the environment minister.

“Not all can be blamed on the Ministry of Environment itself, as the ministry is often following orders from higher levels” Mr. Hardtke said. “But the sellout we have witnessed over the last years via the ELC scam shows significant amounts of criminal energy.”

Global Witness says real reform will have to include the prosecution of the worst offenders.

Mr. Sopheap said posterity would be their judge.

“History,” he said, “will mark our name.”

(Additional reporting by Matt Blomberg)