In December 1923, a young man who would become one of France’s foremost writers was arrested for stealing statues from the Banteay Srei temple in Siem Reap province.

Andre Malraux, who at 22 was already a familiar figure in literary circles in Paris, had lost all his wife Clara’s money on the stock exchange earlier in the year and, to get out of their financial hole, had come up with a scheme of stealing Khmer antiquities and taking them back to Europe to be sold.

The French administration’s Phnom Penh tribunal sentenced him to three years in jail, but the appeal court in Saigon reduced that to a one-year suspended sentence.

These trials forced Malraux to spend nearly all of 1924 in Phnom Penh and Saigon. As political scientist and researcher Raoul Marc Jennar will explain in a conference at the Institut Francais tonight, Malraux’s time in the region was a turning point that shaped both the man and the writer. Mr. Jennar addresses this in his new book, “Comment Malraux est devenu Malraux” (How Malraux became Malraux), which was released last month by French publishing house Cap Bear.

“While awaiting trial, Malraux… met Europeans, Cambodians and Anamites, as Vietnamese were called at the time, who showed him the reality of colonial society,” he said in an interview last week. “Malraux turned into a defender of Cambodians against colonialism, which is not known enough in Cambodia.”

Once his appeal trial was over, Malraux went back to France in November 1924, returning to Indochina—the territories administered by France in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam—in February 1925 to launch a newspaper out of Saigon. His partner was Paul Monin, a French attorney who often defended Vietnamese against the French administration.

During that period, Malraux became convinced that France, which had proclaimed its bill of rights in 1789 and portrayed itself as a human rights champion, did not implement those rights in its Indochinese colonies, Mr. Jennar said.

Malraux and Monin called their daily newspaper L’Indochine. Then, after the French government tried to shut the publication down and succeeded in blocking it for three months, they renamed it L’Indochine enchainee (Indochina Chained). This second incarnation of the newspaper was published twice weekly until late February 1926.

“It’s a newspaper that virulently denounced corruption in the colonial administration and the colonials’ behavior toward the ‘natives,’” Mr. Jennar said. “French administration pressure led to its being financially crushed. Freedom of the press was just for newspapers favorable to colonization.”

In the newspaper, Malraux wrote about the trial of Cambodians implicated in the Bardez Affair: the killing of the unsavory French official Felix Louis Bardez after he came to collect taxes in a village in Kompong Chhnang province. During the trial for the killing, held in December 1925, it was revealed that Cambodians were paying the highest taxes per capita in Indochina.

As had been the case during Malraux’s trial, the French administration refused to share crucial documents with the defense and also interfered with witnesses. “The trial was a caricature of justice,” Mr. Jennar said. It ended with one man sentenced to death and five others condemned to life imprisonment in the infamous penal colony of Poulo Condor off the coast of Vietnam.

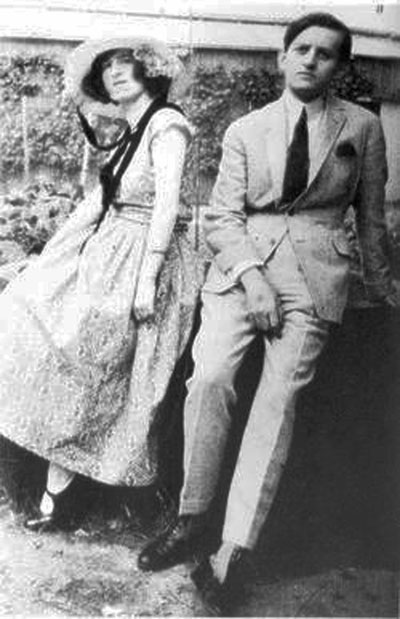

Andre Malraux and his wife, Clara, in 1922.

In his newspaper stories, Malraux took the side of the Cambodians against the colonial justice system. “This trial convinced Malraux that the colonial system cannot be improved, that it must be suppressed…. Independence is a must,” Mr. Jennar said.

“In the newspaper, he also denounced instances of land grabbing, a phenomenon still seen today in Cambodia and Vietnam,” Mr. Jennar said. “Nowadays, it’s no longer colonials but rather multinational companies, no longer colonial administration but rather national authorities. But the phenomenon is the same.”

Sick with exhaustion, Malraux returned to France on December 30, 1925 but continued to write for the newspaper. He would make several additional trips to Asia in the late 1920s and early 1930s. His 1930 book “La voie royale” (“The Royal Way”), which is based on his episode at Banteay Srei in the Cambodian jungle, earned him the French literary Interallié Prize.

In 1933, his book “La Condition humaine” (“Man’s Fate”) was awarded France’s most prestigious literary award, the Goncourt Prize. The book is about the brutal 1927 suppression of communist organizations in Shanghai by the military forces of Chiang Kai-shek and conservative factions.

The man who left Saigon in 1925 was very different from the one who had arrived in Cambodia two years earlier to steal Khmer antiquities.

Prior to his trip to Cambodia, Malraux had had no interest in politics, Mr. Jennar said. When he returned to France, he had become a politically-involved writer. “Today, it’s a type of intellectual we know well. But at the time, it was quite rare, quite new.” It was only during the 1930s that French intellectuals—Malraux among them—would involve themselves in politics to fight the military regimes of Franco in Spain and Hitler in Nazi Germany, Mr. Jennar said.

Malraux joined the French resistance when France was occupied by Germany during World War II and befriended Charles de Gaulle, the voice of the resistance. He served as France’s culture minister from 1959 to 1969 under de Gaulle’s presidency.

Born in 1946 in Belgium, Mr. Jennar spent a decade as a literature professor before taking a job as a foreign affairs adviser for the Belgian government and senate, his first case being the Vietnamese and Cambodian forces’ ousting of the Khmer Rouge in January 1979.

From 1989 to 1999, Mr. Jennar was based in Cambodia working as an adviser to international NGOs and the U.N. Having written his doctoral thesis on Cambodia’s border issues in 1997, he served as Cambodia’s adviser at the International Court of Justice of The Hague for the Preah Vihear temple case, which Cambodia won against Thailand two years ago.

Fascinated by Malraux since his teenage years, Mr. Jennar had intended to write about him for a very long time, but was unsure what he could add to the extensive secondary literature that already exists on the author, he said.

“But I eventually realized that, regarding the 26 months he spent in Indochina between 1923 and 1925, his major biographers have paid little attention to that period, which would transform Malraux,” he said.

Mr. Jennar’s conference at the Institut Francais starting at 7 p.m. will be in French with simultaneous translation in English and Khmer.

The conference will be preceded at 5:30 p.m. by a screening of Rithy Panh’s latest film, the brilliantly crafted documentary “La France est notre patrie” (“France is our Motherland”), which shows France’s colonies through the eyes of French people who lived in or visited them.