Prime Minister Hun Sen has made clear his belief that the U.S. has no grounds for lecturing Cambodia about a war-era debt that has ballooned to $500 million, saying that the money was stained by the blood spilled during a brutal U.S. bombing campaign in border areas.

But that didn’t stop U.S. Ambassador William Heidt from stepping onto his proverbial soapbox when asked about the loan during a media roundtable last week, noting that he had helped draft a deal that went unsigned as an officer at the U.S. Embassy two decades ago.

“I come back; the issues remain unsolved; and that number has grown to $500 million, about. So to me, I think that is unfortunate, I think that’s not in Cambodia’s best interest to keep letting that grow forever,” he said, rubbing salt in the wound by noting that Cambodia was among only four countries in arrears to the U.S.—the others being Sudan, Somalia and Zimbabwe.

“I’m saying it’s in Cambodia’s interest not to look at the past, but to look at how to solve this because it’s important to Cambodia’s future,” the ambassador added.

Days later, Mr. Hun Sen again raised the debt during one of his many public addresses.“Oh America, and U.S. President Donald Trump, how can this be? You attacked us, and demand that we give money. So I do not understand this point.”

Although his grandstanding against foreign criticism—over human rights abuses, political jailings and corruption—is commonplace and often dismissed, observers say that when it comes to money borrowed by the U.S.-backed Lon Nol regime, this time Mr. Hun Sen may have a point.

Though the U.S. has refused to entertain Mr. Hun Sen’s desire to write off the debt, others have noted the hypocrisy of the U.S. demands—considering that it was U.S. bombs, meant to flush out Viet Cong forces in the east of Cambodia during the Second Indochina War, that created the need for loans in the first place.

“The U.S. government has never accepted legal responsibility for the tremendous damage it inflicted on civilians and the country of Cambodia during the war,” said Elizabeth Becker, an American journalist and author who covered the war—including the bombing campaign in 1973.

“Presumably this is out of fear that the U.S. might have to pay war reparations for the destruction and that former American officials might be sued,” she said, adding that plenty of the bombing went on without the knowledge, much less the agreement, of Cambodian authorities.

“To continue to hold the Cambodian government legally responsible for an old war debt is hypocritical and immoral,” she added.

If repayments were to be made, Ms. Becker proposed that the U.S. should redistribute the money among Cambodian communities whose lives were affected by the bombing.

“The U.S. owes Cambodia much more in war debts that can’t be repaid in cash,” she said.

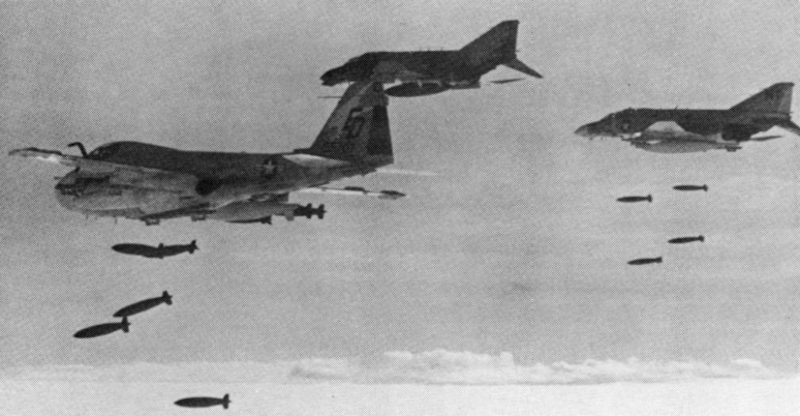

For eight years starting in 1965, it is believed that the U.S. dropped 2.75 million tons of ordnance on more than 113,000 Cambodian sites. Estimates for the number of Cambodians who lost their lives range from 5,000 to more than half a million.

Between 1972 and 1974, the U.S. Department of Agriculture funded $274 million in purchases of U.S. cotton, rice and flour by the Lon Nol regime, then an ally in the war to stem the spread of communism in Southeast Asia. The debt has almost doubled due to interest accrued over the decades since.

Song Chhang, an information minister under Lon Nol who now lives in California, recalled in a recent Facebook post how the campaign led to the regime’s desperate need for financial assistance. “Cambodia’s rice fields were carpet-bombed by the Americans while Communist Khmer Rouge and Vietnamese roamed the countryside, recruiting troops and killing government officials and soldiers,” he wrote.

“This was what hurt most food production in the country. Over two million people left their villages and food producing areas and took refuge in Phnom Penh, the capital, for security reasons, creating another dire need for food for the Lon Nol government while its troops were fighting.”

Kenton Clymer, author of “The United States and Cambodia, 1969-2000: A Troubled Relationship,” said Mr. Heidt’s suggestion that Cambodia should stop dwelling on the past was “not justified,” though the tough talk over the debt fit with Mr. Trump’s message to the world.

“The renewed American demand for repayment of the debt is very much in line with President Trump’s unsubstantiated assertion that the United States is being taken advantage of by countries all over the world,” Mr. Clymer said in an email.

One of the consequences of refusing to make repayments, Mr. Heidt noted, would be that it could lead to problems in borrowing from international financial institutions and commercial markets.

Miguel Chanco, the lead analyst in the Asean region for the Economist Intelligence Unit, agreed that Cambodia’s refusal to service its overdue debt to the U.S. could “hamper its ability to borrow cheaply from global capital markets.”

While the U.S. could not necessarily compel Cambodia to start making repayments, the Trump administration could “certainly apply pressure on other aspects of their bilateral relationship,” he said, noting that it would be wary of pushing Mr. Hun Sen further into the arms of the Chinese.

“Whether or not Washington will apply such pressure diplomatically is another matter altogether. I think that the U.S. would be very reluctant to pressure Cambodia to pay, as this would risk pushing the country deeper into China’s orbit,” he said.

In his speech earlier this week, Mr. Hun Sen also used the debt debate to paint the opposition CNRP as a puppet of the U.S.

“I hope political parties in Cambodia will support the cancellation of the debt. But the opposition, I believe, will not support it because it’s afraid since it’s a subordinate of the U.S.,” the premier said.

Kem Monovithya, the opposition’s deputy director of public affairs, said it was ultimately down to the U.S. to form its own position on the debt, but claimed the Cambodian government’s behavior was not helping its cause.

“It’s difficult to imagine the U.S. would do a favor for a government that is bashing the U.S., [is] corrupt and is increasingly oppressive,” she said.

Asked how a prospective CNRP government would approach the issue, Ms. Monovithya said it would seek relief by “presenting how that relief would benefit Cambodia, for example, we would invest the amount owed into our education sector if we don’t have to pay back to the U.S.”

Despite the rhetoric of the U.S., David Chandler, a prominent historian on Cambodia, said it was unrealistic to think that Mr. Hun Sen, who was fighting the Lon Nol regime with the Khmer Rouge when the loans were delivered, would ever pay them back.

“Heidt has to put pressure as he’s told to do,” Mr. Chandler said in an email.

“But I think it is a pipe-dream for anyone in the U.S. government to think that Hun Sen’s government will come up with $500 million to repay a debt contracted when Hun Sen himself was at war with the people who contracted the debt.”

(Additional reporting by Kuch Naren)