VILLAGE 77, KOMPONG CHAM PROVINCE – It has been more than three years since the brokers first swept through this desolate village, preaching the good life to young women too tired and poor to imagine a future beyond cassava fields and garment factories.

Door to door the brokers went, playing on fantasies of romance and riches, selling the opportunity of a dream life in China.

They worked on the mothers and fathers, too. Mostly middle-aged Cambodian women themselves, some of them got their start in the trade after sending their own daughters on the journey into the unknown.

“Why would they stay? What is there for young people to do here?” said Thim Narin, who works on women’s issues with rights group Adhoc in the province, during an interview at her office earlier this year.

Fields of cashew trees and cassava bushes are the only real source of employment here, and that work is seasonal, leaving Village 77 populated mostly by grandparents watching over children, the middle generation gone in search of cash.

Many of the men go to labor on construction sites in Thailand or Phnom Penh; some go to garment factories here or industrial production lines there; and a less fortunate few wind up as slaves on Thai fishing boats.

For the women—many of them unschooled teens when they leave home—Cambodia offers little more economic opportunity than tedious, low-paid factory work or the risky business of selling beer or sex. So with the blessing of their parents, many migrate.

“They have to leave. Anything is better than staying here,” Ms. Narin said.

Despite a ban, women still find their way to Malaysia to work as domestic servants, but the horror stories of rape, abuse and enslavement are well known. Doing hard labor in Thailand’s factories or on construction sites is hardly more appealing. South Korea, too, has been a destination for thousands of desperate young Cambodian women, and many have found a good life there, marrying happily, working in electronics factories and receiving fair pay.

But South Korea requires its migrants to first learn the local language, which costs money that most families here don’t have, and requires a basic education, which is almost as scarce. Life in China, on the other hand, comes with hundreds of dollars in cash—paid up front—and the promise of ongoing remittances to any family whose daughter will marry a stranger.

“They think that in China they can just relax and wait for a portion of the husband’s salary to send home,“ Ms. Narin said. “Korea involves work.”

So, she estimates, about four of every ten young women who leave Kompong Cham end up in China via this informal bride trade. And some of them, she says, become part of the recruitment force themselves, convincing other women in their home villages to marry a Chinese man and keep up the supply.

And regardless of their role, they are all in the bride trade for one reason, according to Ms. Narin: “to settle family debt.”

* * * *

A scythe came crashing down on Lean Heng’s forehead. The 50-year-old was in her earthen-floor home, sleeping in her own bed. Her youngest son and his wife had already been attacked in the next room by the divorced husband of her eldest child.

“He came to kill us,” Ms. Heng said last month, pressing down on a handful of hair to reveal the rugged scar left by the single blow.

Sitting alone outside her low-slung concrete home, its white facade red with dust, the front wall scrawled with faded phone numbers, the grandmother explained how that attack also cost her a granddaughter.

The jealous ex-husband had opened up a gaping wound on her daughter-in-law’s head, from above her hairline almost to her eyebrow. She spent months in the hospital, with her family shuttling back and forth between Kompong Cham and Phnom Penh. The woman had skin grafted from her leg to her face. The hospital bill for the three ran upwards of $5,000.

“We are not rich people,” Ms. Heang said, turning toward a home devoid of material goods save for a set of speakers her son bought for a party they never had. “What can we do?”

The grandmother borrowed money from a microfinance company but that debt soon became untenable, with the family—including four grandchildren—running on the salaries of two sons slogging it out on building sites in Thailand.

And then, late in 2012, the brokers came.

“We sent her to China because we could see no other option,” Ms. Heng said of her eldest granddaughter, Ren Srey Voeun, then 17, whose father had wielded the scythe. “Now she has a baby.”

Ms. Heng said her granddaughter had been seduced by the brokers with their tales of handsome men and high fashion, and that she, too, was taken by their bluff. But in addition to tales of romance, the brokers also had cash and promised remittances, which the family needed to stay afloat. The grandmother makes no secret of the fact that the transaction was about money.

“We thought, if she doesn’t go, how will the family ever get out of trouble?” she said, sobbing, unable to make eye contact as she spoke.

Soon after Ms. Srey Voeun landed in China, however, it became apparent that migrating for marriage would not be the solution that her family so desperately needed.

The teenager was sold to a man much older than her, a day laborer on farms and construction sites. She was taken to a remote area—she doesn’t know where because she cannot read or speak the language—to live in a small home with her new extended family.

Her husband’s sister despised her; the family was poor, not much better off than what she had left; she was the last to be rationed food; remittances were minimal, and few and far between.

Ms. Heng says her granddaughter, now 21, wants out, and that the family wants her back, too—the microfinance company be damned. But the young woman’s husband holds all the power, having paid for a bride who doesn’t know where she is or how to get home.

“We got $700 from the broker,” Ms. Heng said, weeping in front of her home. She cries often, she said, particularly around the holidays, when many of Village 77’s migrant workers come home to their families. “It feels like we sold my granddaughter.”

* * * *

Kompong Cham has for more than a decade been a source for East Asian men seeking foreign brides. Taiwan and South Korea both had thousands of Cambodian women marry into their countries until new legislation was introduced—in 2009 and 2010, respectively—to regulate a trade that had entered the realm of human trafficking.

Organizations and police from the national level down admit they have no real data on the latest trend in marriage migration, but the data they do have shows that certain areas remain strategically targeted by those whom almost everybody here calls “the brokers.”

“They go where the people are poor, where people are in debt,” said Thol Meng, who, as deputy chief of the anti-human trafficking bureau in Kompong Cham, has a team of 17 officers at his disposal—the largest such force in the country, outside of Phnom Penh.

During an interview at his office in the provincial capital, Mr. Meng explained how the furthest reaches of Chamkar Loev district, including Village 77, as well as similarly impoverished parts of Tbong Khmum and Stung Trang districts, were some of the hardest hit in the country.

After identifying a target area, he explained, squads of brokers sweep through communities, make their pitch to as many families as possible, and get out.

“They are gone before we know they came,” he said, adding that police typically do not know an area has been hit until months after—usually via a complaint from a family regretting its decision. By that time, the migration process could already be secretly underway for any number of young women in a village. The brokers also multiply their reach, he said, engaging locals to source more prospective brides, keeping the dream alive.

“Some of the locals work for the brokers, but they don’t know the full impact of their actions,” Mr. Meng said. “All they know is that they are getting paid $100 for each person they find that agrees to migrate.”

After a woman agrees to the journey, she eventually travels to Phnom Penh, where she is received by the “second broker,” who is tasked with organizing logistics and documentation—passports, visas, flights. The woman then goes home and waits, usually about a month, before being called back to Phnom Penh, where she may wait in an apartment for a few more days before flying out with a batch of would-be brides.

As a narrative of sale and abuse began to take shape around this business, the Cambodian government in 2014 pressured the Chinese Embassy in Phnom Penh to more stringently assess the visa applications of young, single Cambodian women. Initially, this forced part of the trade underground and made it more dangerous. Women started traveling overland through Vietnam, being passed from broker to broker, and through a clandestine border crossing via gang-controlled smuggling routes into the south of China.

However, some are still trying to take the air route, with a young couple arrested at Phnom Penh International Airport and charged with human trafficking as recently as September.

The husband and wife, in their mid-twenties, told police that they were set to earn $10,000 from a China-based gang—of Cambodian and Chinese citizens—for sourcing two young women, organizing their passports and visas, and seeing them onto a late-night flight to Shanghai.

Mr. Meng said he had forwarded more than 20 trafficking cases to the Kompong Cham Provincial Court since the start of 2015. All of the accused brokers are middle-aged Cambodian women. But his work is useless, he said, unless the problem is addressed at the national level, and in cooperation with Chinese authorities.

“If they don’t arrest the traffickers in China,” he said, “their supply lines here replenish and the problem remains.”

* * * *

Long Chanthy is 20. Her passport says she was born in July, 1989. The passport says her name is Chhea Leakhena. She doesn’t know why.

Ms. Chanthy had been living in China’s southeastern Jianxi province—married to a bulldozer driver after a broker gave her parents $700—for almost two years when she got a phone call late in 2014 from her father, back in Village 77.

“He said, ‘Your mother wants to start organizing for girls to be sent to China,’” Ms. Chanthy said last month outside her family home, where she was nursing her newborn baby boy. “I told him that the situation had changed, that she might be arrested.”

The warning was ignored. Ms. Chanthy’s mother got into the game, attempting to seduce girls with the same Chinese dream her daughter was chasing. But it didn’t last long. She was arrested in March 2015 and spent eight months in the provincial prison.

“When I sent my daughter it was very easy,” said Ms. Chanthy’s father, Troeung Long, perched stiffly on a wooden platform in his front yard, a catheter trailing out of his sarong.

“Now, the government is preventing it,” he said. “Some other women around here are still looking for young women to send to China, but they always fail because the police have their spies here. It’s been quiet for a year.”

But the mother, Yorn Thoeun, is out of prison, and the couple is already plotting the migration of another family member: their youngest daughter, who is 16 and works as a waitress in the tourist center of Siem Reap City.

“My daughter planned to take her sister when she goes back to China,” Ms. Thoeun said, cautiously. “But we are still saving for the passport.”

She explained how all four of her children had left home in search of money to support their aging parents. Her two sons work in garment factories, but remittances from China—up to $3,000 a year from the bulldozer driver—still make up most of their income.

“We don’t work. We just wait for the money from China,” she said, adding that, without the inflows from their offspring, her debilitated husband “would have to go back to being a fortune teller.”

The mother later changed her story, saying there was “no way” she would send her youngest daughter to China. Away from the others, the father said he was keen to hand the teenager over to a Korean man in Phnom Penh for a one-off payment of $10,000.

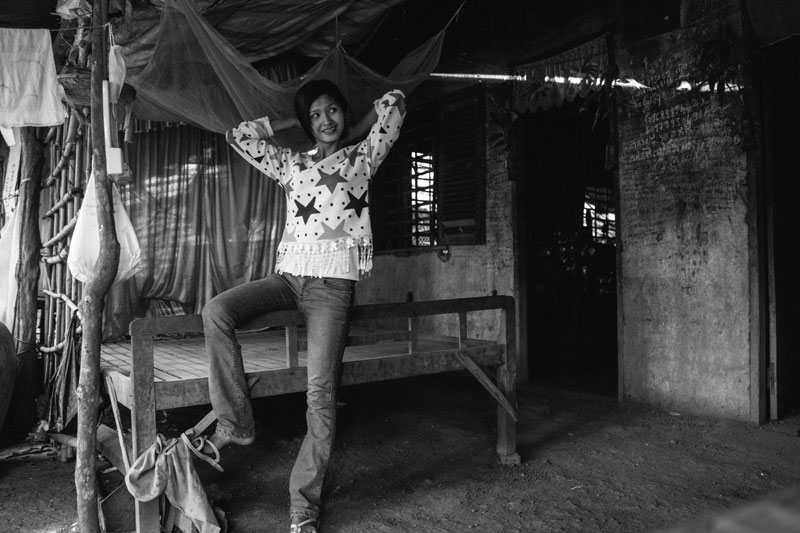

Meanwhile, the teenager flitted around the cobwebbed family home, doting over her new half-Chinese nephew and brushing her long hair, seemingly unperturbed, but certainly not unfamiliar, with being spoken about as a commodity. Still, though, she said she had her own plan for her life.

“I want to live in Cambodia and marry a Cambodian man,” she said.

Cross-border marriages throw up a host of obstacles for couples, not least the one that Ms. Chanthy, the young mother, is currently dealing with.

When she became pregnant midway through last year, authorities in Jiangxi told her that her baby would not be granted Chinese citizenship, she said. She doesn’t know why, but suspects it could have to do with the legitimacy of her marriage, which she is also unsure of, as there was no official wedding ceremony and she can barely communicate with the man she calls her husband.

Afraid that hers would be a stateless baby, she came home to give birth to her son, Lee Koo Yang—or Ly Sam Ath. Her husband accompanied her to lobby officials at the Chinese Embassy to give the baby dual citizenship, or perhaps to formalize their union.

“I want my baby to be a normal citizen in China,” she said, nuzzling her son. “Ker ei baobao,” she told him in Chinese, “Baby cute.”

* * * *

Beijing scrapped its highly controversial one-child policy in October, but its legacy remains.

Aside from giving rise to millions of sex-selective abortions and abandoned girls, with male offspring preferred for perpetuating of the family name, the now-defunct policy has been—and will continue for years to be—a great force pulling foreign women to China.

It is projected that by 2020 there will be 30 million Chinese bachelors who cannot find a wife; they are known in China as guang guan, or broken branches, representing dead ends on the family tree. Many of them are poor, marginalized, disabled.

A lack of statistics paired with the shifting tactics of the brokers and prospective husbands makes it difficult for families and rights groups to monitor migration for marriage or be proactive about its dangers. Stories of confinement, slavery, violence, forced abortions and rape—by both the husbands and their family and friends—have been accompanied by tales of escape and periodic homelessness, as well as reports that Cambodian officials in China are ignoring pleas for help, or are even complicit in the trade.

With little or no knowledge of the local language, and with their husbands or brokers holding their passports, Cambodian wives risk everything if they attempt to run away. She is a foreigner with no documents and no ability to explain her situation to strangers.

Beijing’s embassy in Phnom Penh declined to share data on Cambodian women granted visas to travel to China over the years. It said it did not deal with Cambodian-Chinese marriages. Asked in September for statistics, spokesman Cheng Hongbo said only that the number of women traveling to China for marriage had “definitely decreased,” following efforts to restrict the trade and stem the abuse.

The spokesman said the embassy paid strict attention to the visa applications of young women, somewhat restricting the flow of potential brides, but that the same scrutiny was not in force at the Chinese Embassy in Ho Chi Minh City, where Cambodians are also free to apply for permission to enter China.

For those who do make it, the legal age for women to marry in China is 20, explaining the need for falsified birthdates on passports. The nuptial process is largely the same as for locals, and the offspring of legitimate marriages would be born Chinese citizens, he said. Divorce and separation, meanwhile, can be a logistical mess, requiring couples to formally separate, with the agreement of both parties, before a bride can leave China.

Aside from taking out radio and television spots to inform Cambodian women of the dangers of migrating for marriage, the Cambodian Foreign Ministry can only scramble along behind the problem. Just last month, three more women—two of them from Kompong Cham—returned home with the ministry’s assistance.

The three had flown into Guangzhou, legally documented and ready to be married off, but were intercepted by consular officials at the airport, according to ministry spokesman Chum Sounry. “The Chinese police concluded that this was human trafficking,” he said, adding that two Chinese men were arrested for bringing the women over.

But the prosecution of these “human traffickers” is rarely clear-cut.

Cambodia’s inter-ministerial committee on human trafficking has been working with Beijing to develop an “action plan” to address the issues of cross-border marriages, according to chairwoman Chou Bun Eng. However, the plan focuses on ensuring that Cambodian women are migrating and marrying with proper documentation and does not directly target the push-and-pull factors behind the trend.

Ms. Bun Eng said that on a recent trip to China she met a number of Chinese-Cambodian couples “living happily,” and that China’s Ministry of Public Security informed her that thousands of others were doing similarly.

And as most of the young Cambodian women who go to China do so voluntarily, it is beyond the government’s reach to simply outlaw the trade, she said. “We can’t just stop them from going—we would be violating the rights of our people.”

* * * *

“At my age, it’s impossible to find a wife in China unless you have lots of money.”

Koi Chen Sing, a 39-year-old Chinese laborer, was in Cambodia last month for the first time, visiting his in-laws with his wife, Chroek Sokly, who claims to be 26 but seems much younger.

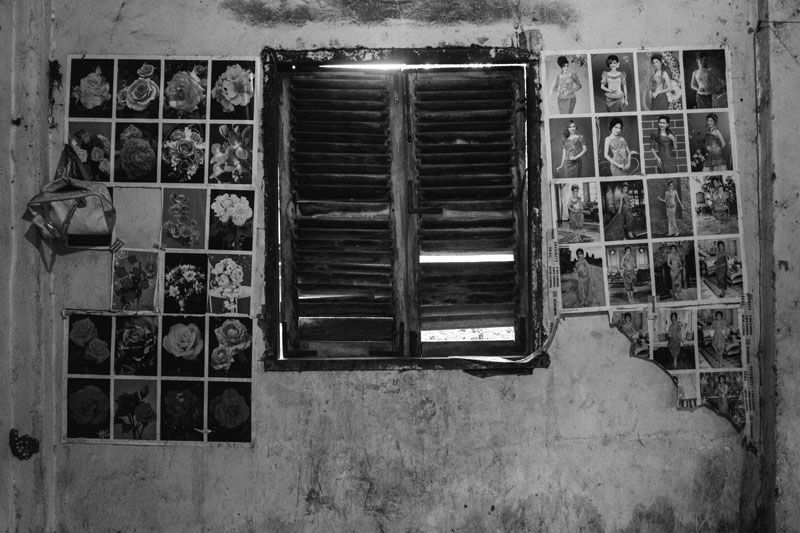

Surrounded by uncles and aunts in the family’s home in Veary Koeut village—next to Village 77—Ms. Sokly explained how, after arriving at an unknown Chinese airport as a bride-to-be in 2013, she was driven to the apartment of a Cambodian woman and her local husband in a town she didn’t know.

The host presented her with a photo of a tall, slim man with Photoshop-fair skin. She asked if Ms. Sokly would object to that man becoming her husband. She did not. “If I did not agree, I would have had to wait in that house,” she said.

Ten days later, the man from the photo appeared in person, along with a second bachelor. Ms. Sokly and another young Cambodian woman—at the same stage in the pairing process—were primped as if for a date: dresses, lipstick, perfume. The four ate lunch together, sharing shy looks and gestures. The women could not speak a word of Chinese; the men had never heard Khmer.

“I just looked at him and thought, ‘He will be good to me,’” Ms. Sokly said absentmindedly as she flicked through her smartphone. “I thought, ‘Maybe this is my destiny’.”

The prospective couple parted ways and were given three days to ponder their futures. Ms. Sokly said that for those 72 hours, “I thought only about him.”

About 60 people were at the wedding—a modest showing by both Cambodian and Chinese standards—all of them from the groom’s side. The bride said she was “acknowledged, accepted” by the family, though the wedding was far removed from the one she had long dreamed of.

“It’s very different to a Cambodian wedding,” she said of the event, which was over in a few short hours. “They have fireworks, but there are no stacks of giant speakers for the party. I could not even get a Khmer-style wedding dress.”

* * * *

Ms. Sokly now has a 1-year-old baby, Chen Sing. The three live together in a second-floor apartment near a small town in the coastal province of Fujian, where she has scores of recently married Cambodian friends. Life, she said, is “really no different” from home, aside from the food.

“There is no Cambodian restaurant here, so we can’t get the food we want: rice porridge, prahok,” she said. “But we always meet to hang out, have small parties, drink together when the children have birthdays.”

She is happy with her life and feels safe in her surroundings, she said—so safe that she has not considered what she might do should her situation soured. Remittances from her laborer husband are only a few hundred dollars every few months, but she still dreams of making her family rich.

“I will just let my destiny take its path,” she said. “Once sea water flows away, it never returns.”

* * * *

Ms. Sokly is an example of why combating—and even classifying—the migration of women to marry in China is so difficult. Many of the young brides say they are happy in their new lives, partly because they are able to help support their families, which is seen as the duty of every Cambodian child, said Ms. Narin of Adhoc.

“They think they are making everyone happy, and that that is their destiny,” she said.

A year after being assigned to work on the issue of marriage migration in Cambodia’s top province for brides, Ms. Narin is still scrambling to catch up with the brokers as she fields reports of daughters missed, missing and abused.

She said that seven particularly desperate communes—including Svay Teap, in which Village 77 lies—had been almost completely removed of their young people, and that brokers no longer visited them, having “already taken all their victims and moved on.”

Her work is complicated, she explained, by mothers and fathers unwilling to share details of their dealings. She has fielded complaints from parents, only for them to renege after their daughter “escapes” the home she was sold into and finds a new Chinese husband.

“It’s all about finding the right man to send home the most amount of money,” she said.

The Foreign Affairs Ministry spokesman, Mr. Sounry, declined to estimate how many Cambodian women have gone to China for marriage, noting that the ministry had helped repatriate 82 women in 2015 and 59 the year before. The ministry, however, is not always the first point of call when the Chinese dream goes bad.

Chab Dai, a coalition of local NGOs assisting Cambodian women in China, fielded 55 cases of “forced marriage” in 2015. Twenty-one of those women are waiting to be repatriated, according to a spokesman. Launched in June 2014, the cross-border trafficking rescue department of Agape International Missions—a Cambodia-based Christian NGO—has handled 139 cries for help, with 66 of those women still stuck in China, awaiting either the funds or legal documentation to leave, according to department’s director.

Chhan Sokunthea, the head of women’s affairs at Adhoc, which has closely monitored migration for marriage, said she dealt with 31 cases in 2015, down from a high of 91 in 2014. She stressed, however, that the load had only been spread across more organizations and the Foreign Affairs Ministry.

“The number of cases overall is not decreasing,” she said. “It’s the opposite.”

The U.N. is also devoid of data on the topic, its anti-trafficking agency months away from releasing the results of a research project into forced marriages between Cambodian women and Chinese men, according to Sebastien Boll, the regional research analyst working on the project.

“Given the irregular marriage migration flows between the two countries, there are no reliable statistics on this,” he said.

Here in Village 77, most people say they know of only a few women who have migrated to China, but every family asked by reporters had either sent a daughter or knew another that had.

“The young people have been leaving the country since 2013,” said Toeng Yath, the chief of Svay Teap commune. “They are almost all gone.”

Ms. Narin sees no end to the problem, her diary filling fast with the names and numbers of aggrieved families, the wave of returnees only just beginning.

And until an alternative way emerges for young rural women to earn money, or the education of youth in rural Cambodia improves dramatically, China will remain a most attractive option for those laboring their lives away only to live on the edge of poverty.

“As long as there is nothing for them to do here, young women will keep going to China,” she said. And as long as they keep going to China “they will be failed by their own imaginations.”