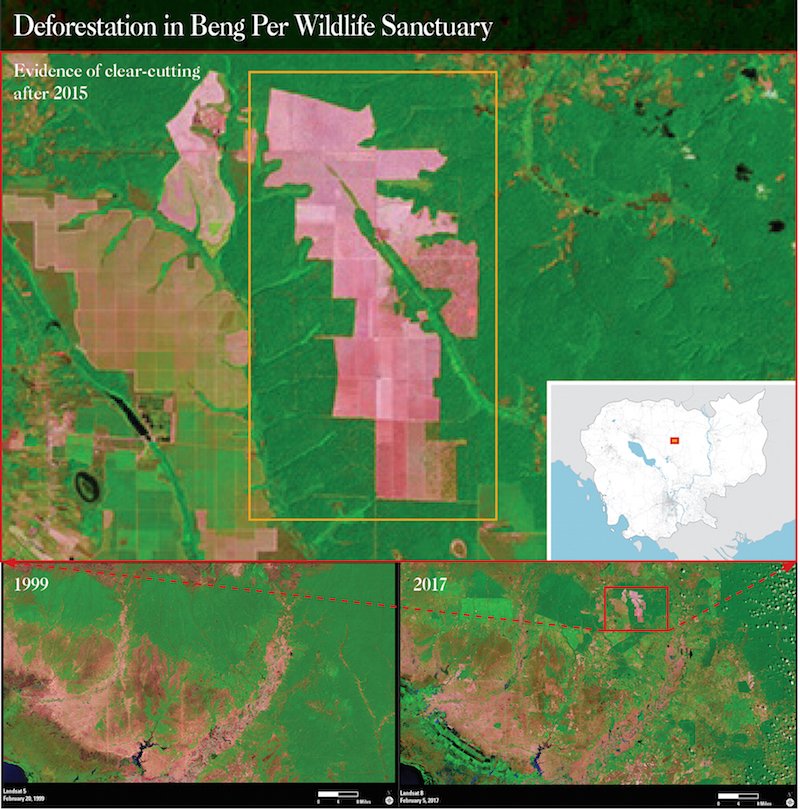

A new satellite image of central Cambodia shows continued clear-cutting of thousands of hectares of healthy forest inside one of the country’s protected areas, five years after the government announced a major crackdown on such logging by rubber plantations.

The image, published online by the U.S. Geological Survey in March as part of an ongoing series of satellite shots from around the world, captures the 243,000-hectare Boeng Per Wildlife Sanctuary twice, once in 1999 and again in February.

It shows more than a third of the sanctuary’s once lush forest canopy now replaced by rubber plantations or cleared in preparation for agri-business.

Most of the damage was done before the government put a freeze on the approval of new Economic Land Concessions (ELCs)—vast tracts of state land leased out to private companies to grow cash crops—and ordered a review of existing ones for breaches of contract in 2012.

But the clear-cutting has continued in breach of national laws.

The satellite image from February shows thousands of hectares were cleared since January last year. Global deforestation data up to the end of 2015 compiled by Global Forest Watch, an online forest monitoring system that also uses U.S. satellites, shows the same area mostly intact.

The recent clearing cuts across two adjacent ELCs, both tied to businessman An Mady: CADI and the eponymously named An Mady Group.

By law, companies are required to secure the approval of local residents before starting their projects and to carry out social and environmental impact assessments to ensure they avoid or mitigate any serious damage. In practice that rarely happens, and the government has largely ignored calls from environment and rights groups to order the companies to stop clearing forest until they catch up.

The government is also supposed to lease out forested land only in parts of protected areas zoned for sustainable development, and only if the forests are already degraded. But Boeng Per has yet to be zoned, and the government has not produced any evidence that the forests were degraded when leased out. Locals and NGOs say Boeng Per’s forests were thriving until the plantations arrived.

Huon Cheanou, chief of Rovieng district’s Boeng Tonle M’rech community forest, which sits inside the park, said Mr. Mady’s plantations started clearing the area in earnest in late 2015 and early last year.

“The company and the authorities never consulted with us about the economic land concessions. They came and cleared the land and encroached on our community forest,” he said.

“In the past, all the forest here was good,” he said. “Now it’s all gone. Now it’s a vast area with no trees. It’s a field now. The resin trees have disappeared and the wildlife is gone. The forest is gone and our livelihoods are affected.”

The government is on record agreeing with him.

A report on protected area management the Environment Ministry released in 2004 with the World Wildlife Fund labels parts of the plantations as an “exemplary plant community.”

Latt Ky, land and natural resources program director for the NGO Adhoc, said the government should have already told the plantations to stop clearing until they fulfill their legal obligations.

“It’s very important to conduct the assessments in advance, to avoid impacting the community in the area. If we do [it with] transparency and accountability, we can avoid affecting the communities who have lived there for a long time,” he said.

Mr. Ky said the government, which is responsible for the land, needed to keep the companies on a tighter leash.

“The government needs to improve collaboration with the companies, and the companies have to work with the communities,” he said.

The rights monitor was reluctant to comment on why that wasn’t happening. Others have blamed the government’s cozy relationship with the plantation owners, some of whom are lawmakers for the ruling CPP or regularly shower the state with generous donations. Try Pheap, whose Boeng Per rubber plantation sits next to Mr. Mady’s, has donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to the government and is one of Prime Minister Hun Sen’s personal advisers. His plantation was also allowed to keep clearing healthy forest without any impact assessments well after the freeze on new ELCs.

According to Global Forest Watch, Cambodia’s ELCs have played a major role in giving the country one of the highest deforestation rates in the world between 2000 and 2014, and the fastest acceleration in forest loss over the same period.

Contacted on Thursday, Mr. Mady said he sold his shares in the CADI and An Mady Group plantations in 2012 and disavowed any further responsibility for them. The Commerce Ministry’s online company database, however, says the companies re-registered in mid-2016 and lists Mr. Mady as a director of both.

Mr. Mady said he sold his shares to a man named Huoch, who could not be reached on the phone number he provided.

Poeung Tryda, director of Preah Vihear province’s agriculture department, which oversees the ELCs in the province, including its share of Beng Per, said the plantations were told to stop clearing a few months ago because they had completed only preliminary impact assessments and never submitted master plans. He said they would need to have their plans and full impact assessments approved before starting up again.

“The company cannot operate until it conducts an [impact assessment],” he said.

Preah Kay thinks it may be too late. An ethnic Kuy, his ancestors had lived sustainably off the surrounding forest for generations.

“Now all the big trees are gone,” he said. “Now we don’t know what to rely on except work for the companies to make a living.”