Drug-resistant malaria is not spreading across Southeast Asia, but is developing independently in isolated pockets, malaria experts said Wednesday in Phnom Penh.

This new knowledge demands a new strategy for combating the potentially fatal parasite, the Cambodian and international experts said.

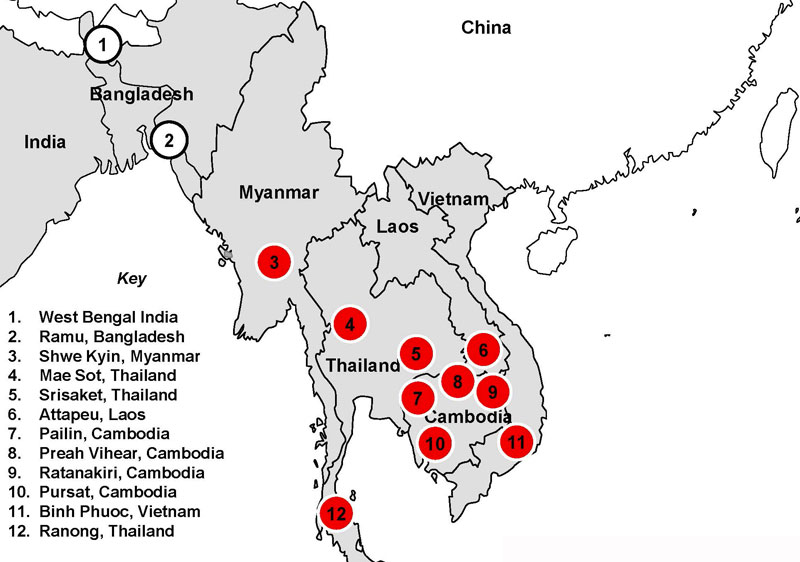

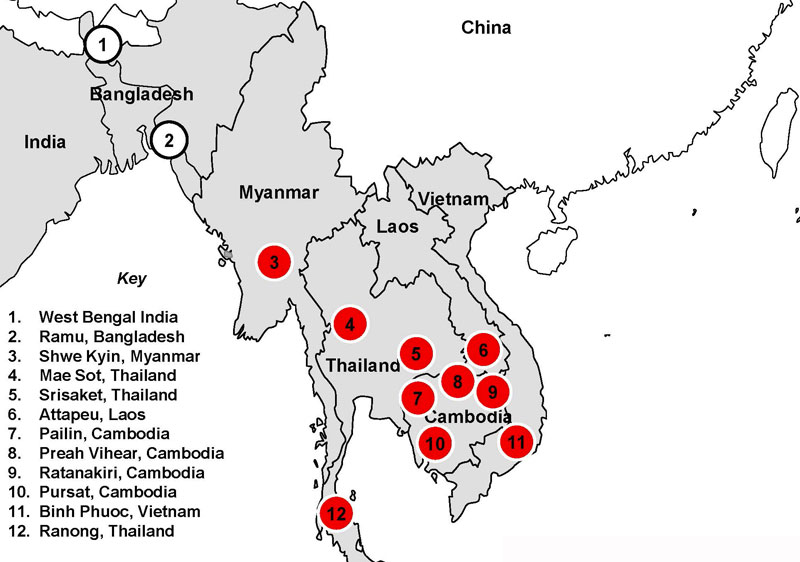

With at least six areas of drug resistance identified, the region needs a “full rethinking” of its anti-malarial strategies, said Dr. Pascal Ringwald, drug resistance and containment coordinator for the global malaria program of the World Health Organization (WHO).

With help from the WHO and other groups, Cambodia has made major gains against malaria since resistance to the best drugs was confirmed along the Thai-Cambodian border in 2007.

Malaria deaths have dropped to zero in Pailin province, the original epicenter of resistance to the best drugs, called artemisinin-based combination therapies, or ACTs.

Last year, the WHO moved its regional hub office for fighting resistance from Bangkok to Phnom Penh, seeking to replicate the success in the other pockets before the resistance reaches Africa. A three-year, $400 million emergency response plan the WHO launched here last April was designed around the idea of stopping resistant strains from escaping the places they were found.

But the WHO’s Dr. Ringwald said resistance is not spreading from a single area. Instead, resistance is emerging independently in multiple hotspots.

“The evidence of multiple emergence is now clear,” he said at a symposium organized by the U.K.-based Malaria Consortium. He compared the malaria situation to fighting not one fire but many.

“This has huge implications, because it’s no more trying to contain something which started here and then spreads, but we have multiple fires in multiple places, and most probably the strategy to contain [and] eliminate will be much different than having something that is spread from an epicenter,” he said.

Mr. Ringwald had no ready answer when Malaria Consortium founder Sylvia Meek asked how they should all adapt to the news. He only said it would need “a full rethinking of what can be done.”

“The old concept that it’s slowly spreading and we need to make a firewall might have to be rethought,” agreed Arjen Dondorp, a professor at the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medical Unit which is researching on drug resistant malaria in Cambodia.

“There are multiple founder populations,” he said. “So it’s not that one clone is slowly spreading westward, it is de novo emergence of various [K-13] mutations.”

K-13 is the medical community’s shorthand for the gene on the malaria parasite where mutations confer it with the much-dreaded resistance to ACTs. This long sought-after “marker” researchers finally found last year is now helping them better map and track the problem.

Mr. Dondorp called its discovery “a huge game changer.”

It also means that the latest map of Southeast Asia showing the WHO’s three-tiered response to drug resistance—where Tier 1 areas have the biggest problem and need the most attention—is already out of date.

That map, from January, shows several pockets of Tier 1 areas between Vietnam and eastern Thailand and another along the Thai-Burma border. Mr. Dondorp said Tier 1 should now include almost all of Burma, a country of about 60 million people.

“It’s all very fast moving now,” he said of the drug resistance. “We know it has already jumped further westward.”

When the WHO launched its emergency response plan for the region in April, its latest map said resistance was not yet even suspected in Laos. Since then, resistance in southern Laos has been confirmed. It believed to be heading north.

But it was not all doom and gloom at the conference.

Mr. Dondorp spoke of a window of opportunity as worldwide malaria cases and deaths continue to fall, thanks in part to a possible “fitness loss” of the parasite. But time was short, he said.

“[T]here might be a fitness loss of those parasites at the moment,” he said. “It’s also very likely that that is a temporary thing, that there will be additional compensatory mutations, making the parasite more fit again and making them even more resistant probably. So we have a time window now to do something about it, before it becomes untreatable, and we have even fitter parasites, and then we are in real, real trouble.”

With resistance now emerging in multiple pockets, he said the best option was not only to keep building “firewalls” around them, but to focus on wiping out malaria species susceptible to ACT resistance.

Cambodia has set itself the goal of zero malaria deaths by next year and zero cases by 2025. It recorded only 12 deaths last year and saw infections drop nearly 40 percent to 42,000.

“I think the only option is that we have to give it a try,” Mr. Dondorp said. “I think Cambodia is well on its way.”

The 3-year, $400 million plan the WHO announced last year is designed to cover the extra cost of fighting drug resistant malaria in the region.

The man on the ground charged with managing it all is Walter Kazadi, the newly arrived head of the WHO’s regional hub for its emergency response plan. At Wednesday’s symposium, Mr. Kazadi said this funding “gap” is likely to grow.