Though a smaller proportion of Cambodians reported bribing public officials last year, more people indicated the government was doing a poor job fighting corruption than five years ago, according to a new report.

The results, which come as the government works to rebrand the country’s image as a nation welcoming and fit for foreign investment, show lingering public perceptions that state institutions are enmeshed in illicit activities.

The latest Global Corruption Barometer, released yesterday by anti-corruption NGO Transparency International (TI), says fewer people think the nation’s level of corruption is declining and that they can make a difference in the fight against graft.

The report, which covers 16 countries in the Asia-Pacific region, surveys “the perception and experience of the Cambodian people,” said Preap Kol, the organization’s executive director, at a news conference yesterday in Phnom Penh.

In Cambodia, researchers conducted face-to-face interviews with 1,003 adults throughout April and May.

More than half of the respondents said the government was not effectively fighting public corruption, up from 15 percent who said the same in 2011 and 2013. Only 35 percent said the government was doing well in its struggle against corruption, behind regional neighbors Thailand, Indonesia and Burma.

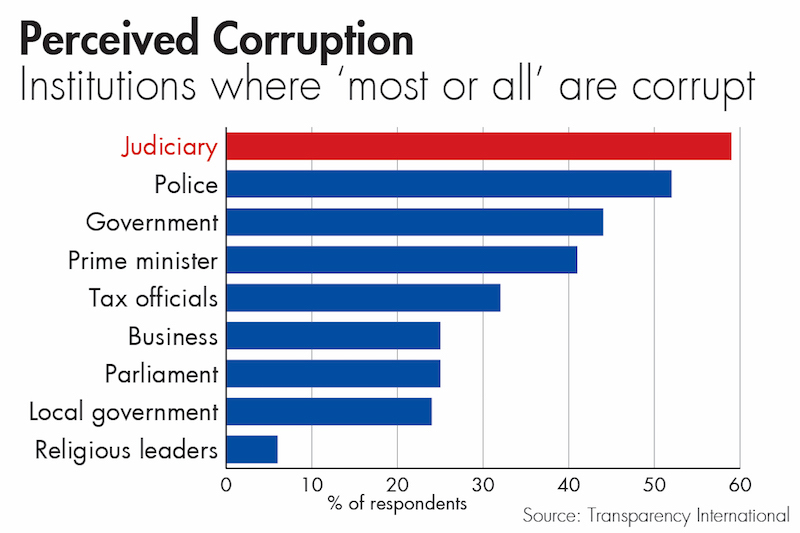

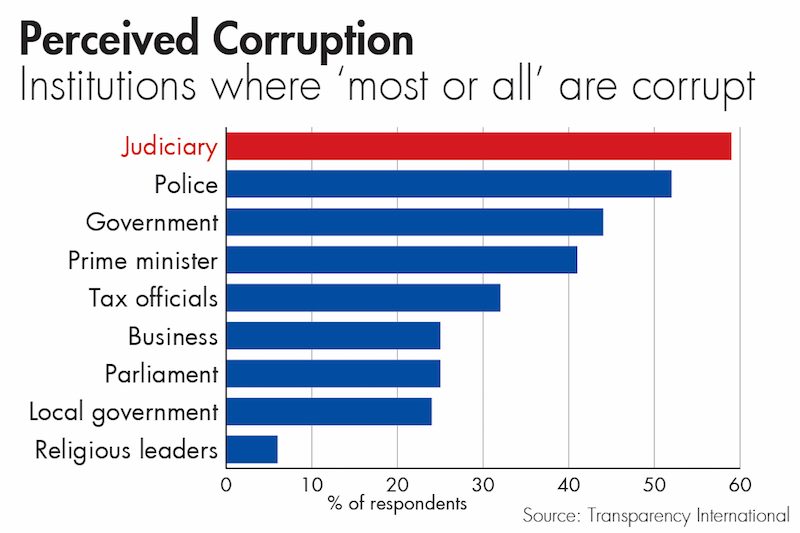

Judges, police officers, government officials, and the prime minister and officials in his office were perceived as the most corrupt public servants, the report says.

Compared to 2011, the percentage of people who said they paid bribes to public servants within the past year had more than halved, from 84 to 40 percent last year. Comparatively more people in Thailand and Vietnam said they had paid bribes, at 41 and 65 percent, respectively.

Because the report surveys average citizens, Mr. Kol said the results may reflect perceptions of petty bribes rather than large-scale graft, differentiating it from TI’s annual Corruption Perception Index (CPI) report, which “focused on the ideas and experience of the experts,” including economists and investors.

“We need to recognize the [difference in] perceptions of the experts and the people,” he said.

Released in January, the latest CPI report again ranks Cambodia as the most corrupt government in Southeast Asia, with a score of 21 out of 100 points.

Last month, during a panel on law, tax and governance at the Cambodia International Business Summit in Phnom Penh, one of Cambodia’s champions of foreign direct investment—and a long-time ally of Prime Minister Hun Sen—acknowledged that perceptions of corruption were hindering business opportunities.

“The prime minister’s campaign against corruption has to be continued because that remains an impediment for foreign direct investment,” said Bretton Sciaroni, chairman of the International Business Chamber of Cambodia and the American Chamber of Commerce.

“We have a reputation and we have to fight against that reputation,” Mr. Sciaroni said.

Yonn Sinat, an undersecretary of state and senior assistant to the Anti-Corruption Unit (ACU), echoed Mr. Sciaroni’s sentiments during the panel discussion.

“We all want to have an investment environment that is conducive to growth, conducive to sustainable development,” Mr. Sinat said. “We understand that the private sector has no interest in paying bribes.”

He said the ACU had signed about 80 memorandums of understanding with private companies to commit to helping stamp out corruption, including Coca-Cola, Prudential and special economic zones in Phnom Penh and Sihanoukville.

Responding to a question about the government’s efforts to counter its reputation for corruption, Mr. Sciaroni and Mr. Sinat questioned the credibility and significance of TI’s CPI reports.

“CPI is ridiculous. The more you fight corruption, the lower score you get,” Mr. Sinat said.

Mr. Sciaroni again acknowledged the government’s image, but said it was getting better.

“We do have a bad reputation and I’m not blind to what goes on here. We have a corruption issue, problem, but there are ways that you can cooperate with the government,” he said. “I think we have made progress.”

But the results of the latest TI report put that assessment into question, with slightly more than one-third of respondents saying the nation’s level of corruption had increased over the past year.

Fewer people think they can make a difference in the fight against corruption. Of those surveyed, 73 percent said they could last year, as compared to about 80 percent in 2011 and 2013.

People cited being afraid of the consequences as the most common reason not to report an incident of corruption.

“They are afraid they can be blacklisted. They can have a problem with those people who are reported,” Mr. Kol said.

To cut corruption, Mr. Kol said the government needed to fight nepotism and conflicts of interest in public institutions, ensure an independent judiciary, and adopt new laws that would protect whistleblowers and provide better access to information.

“They need to improve and invest more effort to fight corruption,” he said.