A highly ambitious stage, music and film production conceived as a way to honor the victims of Cambodia’s civil war and Khmer Rouge regime of the 1970s—unveiled in Phnom Penh on Thursday—will be on a scale hardly ever seen for a Cambodian project.

“Bangsokol: A Requiem for Cambodia” is set to feature the music and film of two giants of the country’s arts world, a New York orchestra and conductor, a Taipei chamber choir, Cambodian traditional singers and musicians, and an Australian director to coordinate all the elements on stage.

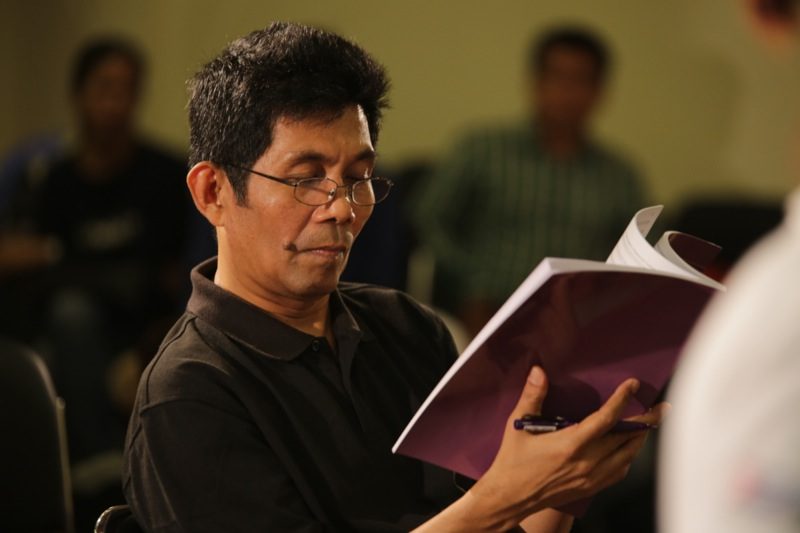

The 75-minute work, expected to premiere in Melbourne in October, also has been conceived as a way to honor the victims of the conflicts of the 1980s, said Him Sophy, the classical composer who wrote the work for orchestra and choir.

“It’s a long time ago for us now. But the tragedy, the violence, the killing still exist in our minds. And so we would like to express our feelings, our thoughts through the music, a piece that I composed for Cambodian people but also for all people in the world,” he said.

“Because now, with the situation in many parts of the world such as the Middle East, Asia, Africa…human beings continue ‘the killing fields’—a catastrophe for our world.”

Mr. Sophy, of the Royal Academy of Cambodia, is one of the few composers to write for both Western and Khmer traditional instruments.

The work—which refers to bangsokol, the white cloth that is placed on a body during a Cambodian Buddhist funeral—was conceived at the suggestion of the NGO Cambodian Living Arts (CLA) almost 10 years ago.

But due to delays, which included fulfilling other commissioned work and having to pull through a long illness, it took Mr. Sophy years to write.

When he first heard excerpts, CLA executive director Phloeun Prim found the work truly daunting.

“We have always thought that this is larger than an artistic piece, that it is somehow kind of a ritual,” he said.

So Mr. Prim suggested a collaboration between Mr. Sophy and Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh, whose feature film “The Missing Picture” won one of Cannes Film Festival’s top two awards in 2013—the “Un certain regard” prize for movies with a unique vision—and was nominated for an Oscar in Hollywood.

“He has this poetic way of telling stories through image. And I thought this would perfectly accompany the music of Im Sophy especially since these two Cambodian artists are from the same generation,” he said. Both Mr. Panh and Mr. Sophy lived through the Khmer Rouge regime as children.

Mr. Panh agreed to the project. “I’ve always believed that one should not compartmentalize forms of expression,” he said.

But illustrating symphony music had to go beyond finding film excerpts to project during the concert, he said. “One must ‘see’ the music and ‘hear ‘ the images, so to speak…and if one did too much with the images, it would distract from the music.”

Mr. Panh created a “poetic collage” closely linked to the music, both images and music also reflecting Cambodians’ identity that those decades of violence have not managed to destroy, he said. “We have a culture, we have roots anchored into a civilization.” This is why the images may include historical footage as well as images from his films.

By this stage, the work needed a stage manager to coordinate the artists and envision a whole. Australian director Gideon Obarzanek was entrusted with that task.

“The challenge is to put all these elements together to make a cohesive, single experience for the viewer. Because it’s live, there are people on stage, there is film on screen, there is a libretto.”

The production will include conductor Andrew Cyr and his Metropolis Ensemble orchestra from New York, the Taipei Philharmonic Chamber Choir, and Khmer traditional musicians, Cambodian singers and a dancer. And above their head, slightly to the back of the stage, there will be a giant screen divided into three panels showing three images simultaneously.

In addition, the Khmer harp will feature for the first time in an orchestra. An instrument played at Angkor, it disappeared from the country about 500 years ago and was recently rebuilt by French ethnomusicologist Patrick Kersale. The singers will use a libretto written by Trent Walker, an American scholar of Southeast Asian Buddhist music who lived in Cambodia for several years.

“The coordination of everything is the challenge,” Mr. Obarzanek said, made even more difficult because the artists will only find themselves together on stage a few days before the Melbourne premiere.

The work will be performed in New York and Boston in December and in Paris in May next year. Plans are to have “Bangsokol: A Requiem for Cambodia” staged in Phnom Penh in 2019 to mark the 40th anniversary of the end of the Khmer Rouge regime.

Mr. Sophy said he believes that by honoring the dead who fell victim to wars and conflicts, this will help heal those who survived. “This may be good for the situation on our planet, our world, and not only for Cambodia,” he said.

Correction: This version of the article corrects the spelling of Mr. Sophy’s name to Him.