When Henri Mouhot’s writings on Angkor were published in 1863 and 1864, triggering in Europe an interest in Cambodia that would never wane, a Scottish photographer by the name of John Thomson came up with the idea of taking photos of the monuments sketched by the French naturalist and explorer.

This was easier said than done 150 years ago, not only because it meant organizing an expedition to reach the site deep in the jungle, but also because transporting the photographic equipment of the day required the services of up to 10 porters.

The trip, in 1866, took Thomson three months, during which he nearly died of malaria. But it led the following year to the publication of his book “Antiquities of Cambodia,” featuring the first 16 photos of the monuments of Angkor ever taken.

However, due to the expensive and lengthy process involved in publishing photos in a book at the time—the text had to be printed first and photographs pasted one by one on blank pages—very few copies of Thomson’s book were released in 1867, and it was never republished.

This is why Joel Montague, an American collector of early postcards of Cambodia and Indochina, and Jim Mizerski, a U.S. photographer based in Cambodia, decided to resurrect the images nearly 150 years on.

Released in Cambodia late last year, their 225-page, large-format book “John Thomson, The Early Years—In Search of the Orient” not only includes the contents of Thomson’s book and photos of Angkor but also tells the story of the man who, as Mr. Mizerski points out, was one of the first photojournalists.

Several books have previously been written on Thomson, mainly because of his photos of China and London street life, which he took during the 1870s. But those publications focused largely on his work and hardly explored the man himself.

“There was actually so little known about the man Thomson that I wanted to find out who he was, what motivated him,” Mr. Mizerski said.

Mr. Montague and Mr. Mizerski expected the project to take one to two years. But researching Thomson’s life and gathering the photos of his journey to Angkor and beyond ended up taking four years. During that time, they contacted private collectors and libraries on almost every continent.

Their initial hope was to take reproductions of Thomson’s work from an existing copy of the book, but the few originals to be found were so brittle that no one wanted to risk scanning the pages, Mr. Montague explained.

“It turned out that the Wellcome Library in London had the original plates, that is, the original negatives that were glass plates,” he said. This enabled them to reprint the work in their book.

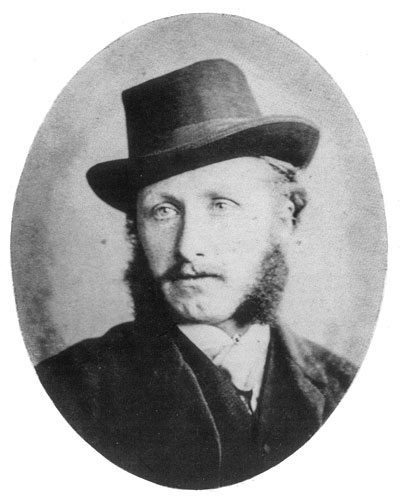

What emerged from their research is a picture of an amiable man who earned a living from what was at the time a very new profession. Born into a modest middle-class family in Edinburgh, Thomson trained as an optician, and also acquired the skills to make and repair watches and scientific instruments. But by 1862, when he joined his photographer brother William Thomson in Singapore, escorting his brother’s fiancee on the month-long boat journey, he had begun to identify as a photographer.

Newly arrived in Asia, Thomson soon set about capturing images that would sell in the thriving port city. This led him to the Straits Settlements—British territories that today are mainly part of Malaysia—an experience he later turned into a book entitled “The Straits of Malacca,” in which he described Malaya as “a spot where leisure seems to sit at every man’s doorway; drowsy as the placid sea, and idle as the huge palms, whose broad leaves nod above the old weather beaten smug-looking houses.”

But the publication of Mouhot’s work in 1863 and 1864 in Europe gave Thomson a new purpose: to go to Siam, as Thailand was then called, and from there to make his way to Angkor. As he wrote in his book on Angkor: “The description given in Mr. Mouhot’s work of the magnificence of the ruined cities which the author found in the heart of the Cambodian forests induced me not only to carry out my resolution of visiting Siam, but to cross the country, and penetrate the interior of Cambodia, for the purpose of exploring and photographing its ruins.”

Even using the most modern photographic technology of the time, this meant a great deal more than simply packing one’s camera.

“Photographers would make this sort of soupy mixture, then pour it over a glass plate, rock it back and forth to even coat the plate and then let it drain off so there would be no ripple or anything on it. Then they used a chemical to sensitize it to light, and had to take the photograph immediately and develop it right after while it was still wet,” Mr. Mizerski explained of the collodion wet-plate process used by photographers in the 1860s.

“If you’re out in the middle of the jungle in Cambodia, that means you have to have a tent as a darkroom with bottles of your own chemicals to do it, chemicals which are rather toxic and burn your eyes and everything. And all of this stuff had to be carried from Bangkok by eight to 10 porters with a supply of glass negatives and chemicals. So it was a huge logistical problem just to get there with the equipment and the supplies.”

It would take Thomson four months in Siam to set up his expedition, during which time he was called in to photograph Siam’s King Mongkut and also ended up taking pictures of several princes.

Since the provinces of Battambang, Siem Reap, Monkolborey and Sisophon were under Siam’s control at the time—those territories would only revert to Cambodia in 1907 through a treaty between France and Siam—Thomson needed authorization from King Mongkut to go to Angkor.

H.G. Kennedy of the British Embassy in Bangkok volunteered to accompany him as his Thai interpreter. In the context of competition between the French and the British in the region, where both nations were eager to expand their influence, French officials whom the pair met at Angkor concluded that Kennedy was a spy.

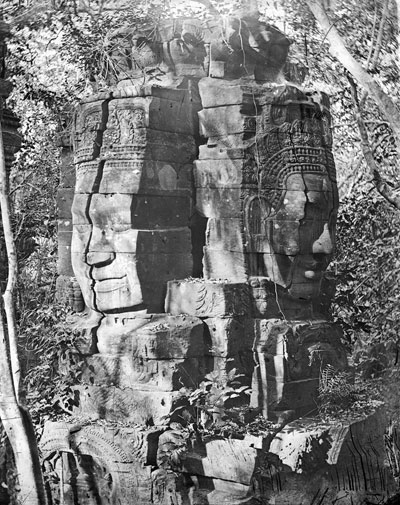

After weeks of traveling on foot, by oxcart and at times by small boat, Thomson finally arrived at Angkor. He immediately took photos of Angkor Wat and the Bayon, focusing on angles that would become classic shots of the monuments.

But restoration was still to come, and the monuments had yet to be freed from the jungle. Writing about the Bayon, Thomson recalled: “This temple is so much shrouded with forest trees, climbing vines, and thorny brushwood, that it was only after a hard day’s cutting…that we succeeded in clearing the tower sufficiently to obtain a photograph.”

A representative of King Mongkut later showed up at Angkor to relay a message from the king requesting that Thomson take plenty of photographs. Upon returning to Bangkok, he would receive a letter from the king asking him to mention in his talks and writings on Angkor that “those provinces of Buttabong and Ongcor or Nogor Siam belonged to Siam continually for 84 years, not interrupted by Cambodian princes or Cochin China. The fortifications of those places were constructed by Siamese government 33 years ago.”

Thomson complied and included the king’s letter in his book on Angkor. Archaeological research has long since disproven King Mongkut’s assertion.

After his Cambodia expedition, Thomson spent several years in Hong Kong—where his fiancee joined him and they married—and China before returning to Britain.

A member of the prestigious Royal Geographical Society and the Ethnological Society of London, he gave conferences on the countries he had illustrated in his work. Later, he became a fashionable society portraitist in London, but also taught photography. He died in 1921 at the age of 84.

As can be seen in the book, Thomson was especially interested in people—he could not resist including Cambodians alongside his photos of Angkor.

“His images, most particularly those of China and London, provided extraordinarily accurate, evocative portraits of people of all classes, from kings to lowly beggars,” Mr. Montague and Mr. Mizerski write.

In the chapter on “cartes de visite,” which were early versions of business cards, photos range from an ordinary girl in Cochinchina to Malay cane sellers and an eastern prince.

Also included in the book is a rare report on Cambodia by Kennedy, the British Embassy man whom the French suspected of espionage. The authors write of the report that it “is perhaps the most acute and detailed analysis of Cambodia in English from the middle of the nineteenth century.” Kennedy noted that the French were aware of Cambodia’s importance and, to strengthen their influence in the East, planned to maintain it as “an important monarchy under their own superintendence,” an expression that well summarizes the French Protectorate.

The book ends with a reproduction of Thomson’s first photography book on China. Entitled “Views on the North River,” this short book is now extremely rare.

This work on Thomson tells the story of an adventurous man who had the ability to make extraordinary expeditions come true. He comes across as an outstanding photographer: His photos are simply beautiful, and in a way that has defied the passage of time.

It begins with a quote from Rosalind Morris, an anthropologist at Columbia University in New York City, that accurately summarizes the authors’ motivation behind four years of toil to produce a book on this pioneer of photojournalism: “Reluctant though we may be, we—anthropologists and historians of photography in East and Southeast Asia—are all John Thomson’s heirs.”