The challenge that French director and actor Jean-Baptiste Phou set for himself was considerable: stage for the first time “L’anarchiste,” the French novel by Soth Polin, an iconic Cambodian journalist and writer, published in 1980.

Adding to the difficulty was the fact that the second part of the book, which Mr. Phou planned to focus on, is set against the backdrop of Cambodia’s political events of the 1970s. The book, written by a man who had fully mastered the philosophical thought of the 20th century, is elegant and complex.

Mr. Phou not only succeeded in turning it into a play, but his production is also a powerful one-actor show—the kind of performance that makes an audience feel they have just lived together a powerful moment in theater.

The filmed version of his French play “L’anarchiste,” presented in France last March and April, is being shown on Saturday at 5 p.m. at the Institut Francais. The screening will be accompanied by a simultaneous English translation done by Mr. Phou himself, and followed by a live debate. Admission is free.

Although modest in scope, this filmed version is a television production rather than the shoot of a live show. “We used five cameras, a sound engineer for sound recording, and adapted lighting for the cameras,” said Mr. Phou. He wrote and directed the show and, when the actor he selected for the role became unavailable at the last minute, he decided to perform it. An artist coordinator, a team of about 10 artists and two dancers contributed to staging the work and developing props and special effects for the play.

The book “L’anarchiste,” which was released in 1980 and reissued in 2011 by La Table Ronde publishing in Paris, includes as Part One a novel that Mr. Soth had first published in Khmer in 1967 and then translated into French.

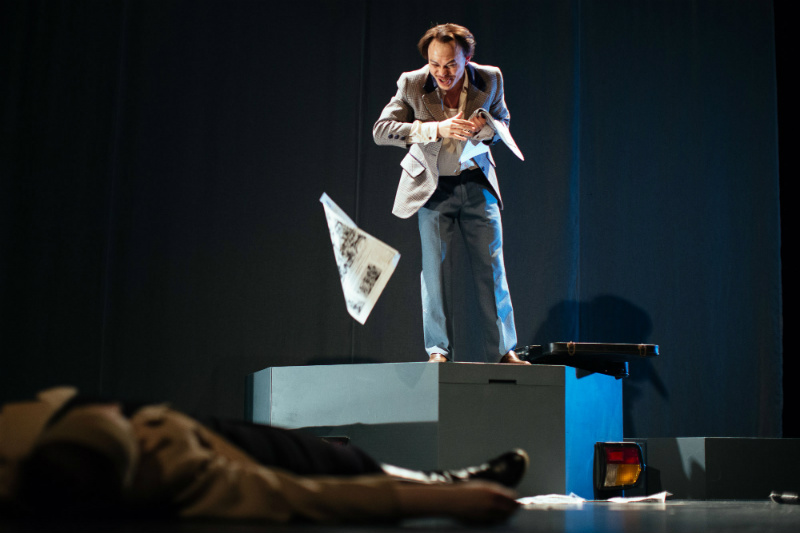

Part Two features the character of Virak, a Cambodian journalist who, he explains, fled to France in 1974 and became a taxi driver in Paris. As the story begins, Virak has just been in a car accident and talks to his passenger, an injured English woman lying unconscious on the ground.

“I need to confess, to free myself of the terrible secret that weighs on me more heavily than a mountain,” Virak says as he begins his story.

Mr. Soth, who was born in 1943 in Kompong Cham province, studied French literature and philosophy and became a philosophy teacher in the 1960s. In addition to publishing a French-Khmer dictionary, he authored several novels—some of them with sexually daring themes—that proved commercially successful.

“Soth Polin brought in new ideas for Cambodian writers and well-informed readers,” said Khing Hoc Dy, an authority on Cambodia’s literature and writers and a researcher affiliated with the Centre national de la recherche scientifique, a French research institution.

“[Mr. Soth] is a person with a broad culture and knowledge of Western philosophy and the world, French and German literature,” he said.

“For this reason, he is extremely complex as most intellectuals usually are. He was strongly influenced by the French ‘existentialist’ movement, and especially by Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre.”

Opposed to communism as well as to King Norodom Sihanouk, who had abolished freedom of the press in the 1960s, Mr. Soth launched in 1968 the daily newspaper Nokor Thom, or the great country, which was quite popular in the early 1970s.

Turning his 258-page book, published a decade later, into a 74-minute play was no small task.

Mr. Phou decided to focus on the second part of the book and bring the character of Virak to life. “The form of adaptation that I picked was to make it a monologue,” he said. “So it was a cut-and-paste operation.”

This took Mr. Phou two full months to accomplish. He then inserted into the monologue moments that would make it more interesting for the audience such as the televised broadcast of the assassination of U.S. President John F. Kennedy in 1963.

“I did not want this to be strictly intellectual…with me standing and delivering a text for an hour,” Mr. Phou said. “I wanted to portray the character in time and space. But this turned out to be a complicated task…as he switches from one state of mind to the next: from frenzy to depression, depression to euphoria, euphoria to sadness, which I wanted to express both through words and physically.”

Mr. Phou succeeds. The persona he developed for Virak using wig, makeup and body language perfectly corresponds to the words he says and the story he tells.

Mr. Phou decided that a dancer, Elizabeth Bardin, would lie on stage to personify the English tourist to whom Virak tells his story. He also used animation inspired by Cambodian traditional painting and a choreographed dance scene performed with Ms. Bardin to address some explicit sexual moments from the book.

In several sections of “L’anarchiste,” Mr. Soth openly addresses sexuality. For the character Virak, sexual intercourse becomes a way of venting anger and frustration rather than moments to enjoy, having little or no relationship with his partners beyond the act itself.

In the book, Virak explains that he chose to be a newsman after being fired from his government position for sleeping with his sister-in-law.

“And this is why I became a journalist,” he says. “It was just because of a mishap. Therefore, here I am, a poète maudit, idolized writer, feared journalist and not as a calling but because of sex.”

As Virak shares his memories in the book, the whole history of the late 1960s and 1970s in Cambodia is brought to life with references to Cold War geopolitics. While those recent facts were known to readers when the book came out in 1980, they might require some explanations for the average audience today.

To simplify matters, Mr. Phou limited historical references in the play, he said. Virak recounts how hard it was to work when he received a letter telling of the death of his parents and his two brothers during the Khmer Rouge regime.

There is another scene in which he confronts, around 1977, a Frenchman who—reflecting what many French intellectuals believed at the time—tells him how “fascinating” the Khmer Rouge regime was. Virak ends up punching him in the face.

In 1977, Mr. Soth had actually researched and written a book with French journalist Bernard Hamel on the evacuation of the cities and mass deaths in Cambodia. Based on interviews with more than 100 Cambodian refugees, which he had conducted, “La grande deportation du Cambodge,” or the great deportation of Cambodia, was one of the first works on the Khmer Rouge regime.

In “L’anarchiste,” the character Virak explains that he fled the country in 1974 after publishing an expose in which he accused leading figures of the republican government of having orchestrated the assassination of Savouth, the education minister.

Mr. Soth had actually fled to France in 1974 with his wife and their two young boys the same day an article came out in Nokor Thom regarding the death of Education Minister Keo Sang Kim and his deputy Thach Chea, who were assassinated during a student protest in June 1974 in Phnom Penh. Mr. Soth never returned to the country.

But is “L’anarchiste” a work of fiction or a thinly disguised autobiography?

“I can’t answer that question,” said Norith Soth, Mr. Soth’s youngest son, now a 41-year-old writer working in the film industry in Hollywood. “I’m sure there’s a lot of him in the book.”

In the book, Virak is an anguished man, blaming himself for his articles against the government that may have weakened the republican government, making it easier for the Khmer Rouge to seize power in 1975. He also blames himself for the government firing his father when his story came out in 1974—his father had been unaware of the story his son was about to publish.

Was Mr. Soth as anguished as his character when the book came out?

“When I was a kid…my dad was very tormented,” said the son. “In the 1970s he was definitely a very tortured person. He was in a lot of pain, I remember that.”

“Today, he’s much more optimistic and very upbeat,” he added.

Mr. Soth moved to Southern California in 1980 with his two sons. In the early 1980s, he launched a Khmer-language newspaper in the Long Beach area and ran it for a couple of years. “My father is not a businessman,” Mr. Norith Soth observed. The paper eventually folded.

Mr. Soth has written for a few publications and worked as a radio journalist at one point. Now 71 years old, he still writes in French and Khmer as much as he can. He earns a living as a shuttle driver at the Long Beach Airport.

Mr. Phou’s original plan was to present the play in France in French and then to stage it in a Khmer adaptation in cooperation with the Institut Francais. Two years ago, Mr. Phou had directed at the Institut Francais the play “Srok Khmer, Nis Hoeuy Khnhom,” or “Cambodia, Here I Am,” featuring Cambodian film actress Dy Saveth, a play he had first staged in French in France.

This could not be done with “L’anarchiste” this year. But Mr. Phou said he hoped to stage the play, in Khmer and in Cambodia, in the near future.