The Chinese firm that was financially backing an ambitious project to develop Phnom Penh’s Boeng Kak neighborhood has pulled out, Chinese Embassy and company officials have confirmed, and no other investor appears to have taken its place.

That makes the Erdos Hongjun Investment Corporation at least the second Chinese firm to divest from the controversial project, which has forced the eviction of some 3,000 families and left a giant, barren sandpit where a lake deemed crucial to the city’s drainage once lay.

It also almost certainly leaves its erstwhile Cambodian majority partner, CPP Senator Lao Meng Khin’s Shukaku Inc., without the capital to follow through on its original billion-dollar plans.

Erdos and Shukaku joined forces in 2010, forming the Shukaku Erdos Hongjun Property Development Co., with Erdos taking a 49-percent stake. The following year, in April, the investment board of the government’s Cambodia Development Council (CDC) approved its plans to cover the filled-in lake with luxury villas, condominiums, office towers and five-star hotels. A list of approved projects for that month listed the company’s assets at $2.17 billion.

But with no visible efforts to develop the site, speculation of Erdos’ split from Shukaku had been circulating since 2012, when the Chinese firm closed down its Phnom Penh sales office for the project and its Chinese managers left the country without any word of their plans to return. Company and city officials repeatedly refused to comment on the matter.

This week, however, a Chinese Embassy official confirmed that Erdos has divested from the project and said she believed that no other firm from China—or elsewhere—has replaced it.

“The company who invested in the project went back to China. Currently I don’t think any company [is] invested in that,” said Cheng Le, who heads the embassy’s economic and commercial affairs office.

Ms. Cheng said she did not know why, or exactly when, the split occurred.

Maggie Zhang, assistant manager at CIIDG Erdos Hongjun Electric Power, which she called a “joint company” with Erdos Hongjun Investment, also confirmed that the Chinese firm had left Shukaku.

“Yes, correct,” she said. “But for the reason, why they stopped [to] invest, I don’t know.”

Ms. Zhang refused to provide contact information for any of her superiors who might have details about the split.

“My company…they don’t want to talk about it,” she said. “It’s confidential information of the company.”

Like the embassy official, she was not aware of any other firm filling Erdos’ place as the Boeng Kak project’s financial backer.

At Shukaku’s Boeng Kak office late last month, Jason Xie told reporters that he had left his position as project director more than a year ago. He would not say why, however, or whether he had been replaced. He would not discuss Shukaku’s history with Erdos Hongjun Investment, either.

Emails to the firm requesting comment went unanswered.

Officials at the CDC, which approved the project in 2011, said Wednesday that they knew nothing about its progress.

At City Hall, Phnom Penh Deputy Governor Khuong Sreng said it was none of the city’s business what Shukaku did with the land.

“I cannot interfere in the company’s internal affairs because the Phnom Penh authority is not a shareholder,” he said.

City Hall leased the 133-hectare project site—since reduced to about 120 hectares—to Shukaku in 2007 for 99 years. With its help, Mr. Meng Khin’s firm proceeded to force some 3,000 families out of their homes as it pumped the local lake full of sand in what was one of the largest single forced evictions in Cambodia since the Khmer Rouge.

The evictions cost the government both loud rebuke from local and international rights groups and money from the World Bank, which in protest put a freeze in 2011 on any new lending to the country.

Undeterred, and with Erdos’ deep pockets, Shukaku forged ahead with a gaudy groundbreaking ceremony at Boeng Kak that July. But the three-story drill brought in for the occasion vanished in a matter of weeks and the sandy site has remained virtually untouched since, sprouting only fields of wild grass where promenades and gleaming glass towers were promised.

Signs of progress did arrive last month, however, when the HLH Group announced on the Singapore bourse that one of its new subsidiaries was preparing to purchase a 1.35-hectare plot at Boeng Kak off of Shukaku for nearly $14.9 million to develop on its own.

Rights groups, however, say Shukaku cannot legally sell off land it is leasing. HLH says the deal is pending a thorough legal review.

In any case, the potential sale is exactly the sort of approach Shukaku was advised against only a year ago.

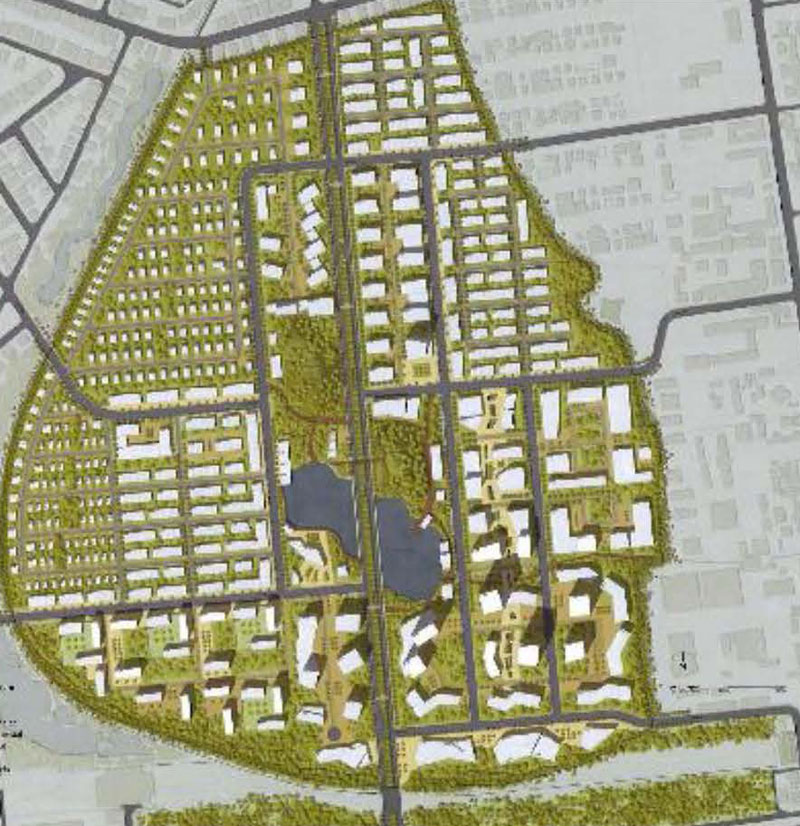

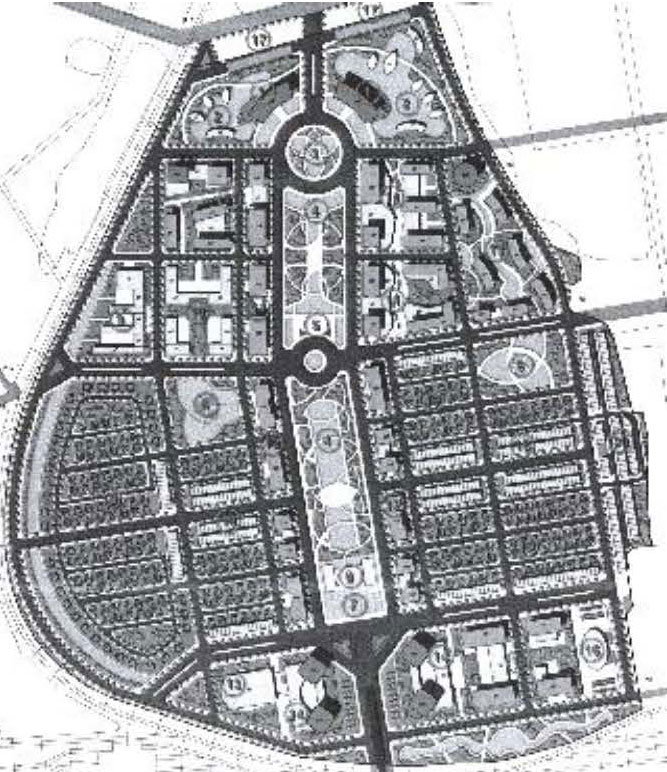

In March 2013, corporate real estate firm CBRE analyzed a pair of master plans for the project site proposed by international design firms Logon and Ong & Ong. Both fit Shukaku’s vision at the time of carefully developing the area in stages with high-end residential space, office blocks and five-star hotels.

In its report, commissioned by Shukaku, CBRE also advised the senator’s firm to sell off parts of the site only as a last resort.

“With the circumstances surrounding this development and to make best use of the assets it is better to develop first and then, if required, sell land later,” the report says.

Whatever development comes first, it adds, “will set a tone for the reminder [sic] of the site and as such should be done to a very good quality. It is best to retain full control of this development and therefore to design and develop in-house rather than selling the land off freehold to a retail developer.”

Ee Sarom, executive director of Sahmakum Teang Tnaut, a local NGO that works on urban development issues, said the pending land sale confirmed long-held suspicions that Shukaku never really meant to develop the area itself or in any coherent way.

“They evicted people and encroached on their land. They said it is for public development. In fact it is just for speculation,” he said. “It’s very clearly land speculation.”

Mr. Sarom worried that selling the land off piece by piece, as Shukaku appears to be trying to do, will only lead to more of the same, incoherent development Phnom Penh already suffers from.

“It’s clear it will not go in a positive way because [there] will be many investors in that area,” he said. “I see many problems in the future.”