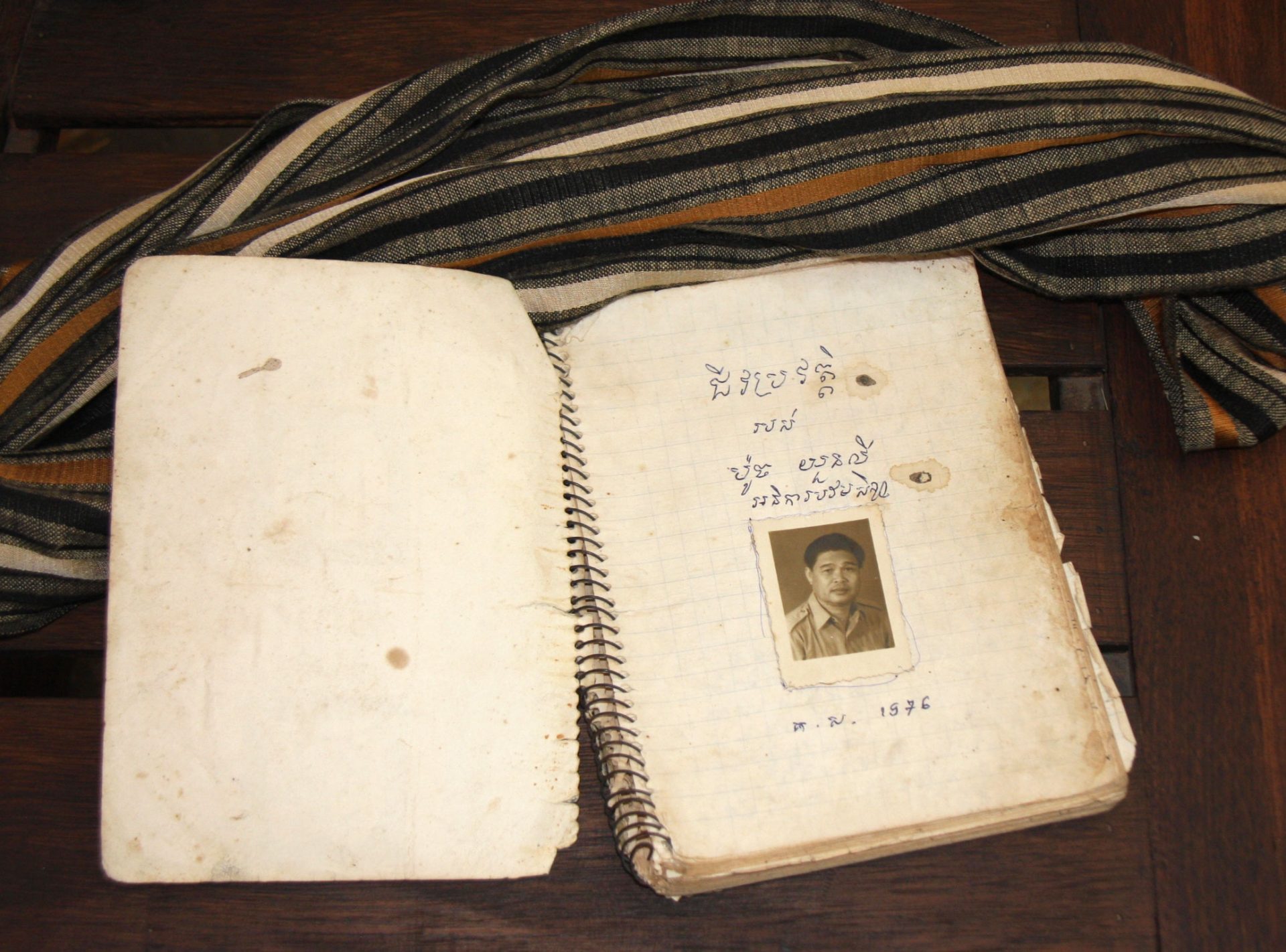

The printed image on the cover of a tattered diary with yellowed pages displays an idyllic scene: three women bathing in an aqua-colored river shaded by trees.

But don’t judge a book by its cover. The diary holds the harrowing, and at times heartbreaking, account of its author, Poch Yuonly, a victim of the Khmer Rouge, and describes the ordeal his family faced during the regime that sent 1.7 million Cambodians to their graves.

His daughter, Poch Viseth Neary—referenced throughout the diary—donated the book to the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam), a research institute dedicated to the study of the regime, on Friday.

Poch Yuonly’s “extremely rare” written account remains one of only four diaries in DC-Cam’s possession that were kept by Khmer Rouge victims, said Youk Chhang, the organization’s director.

“This is something that every survivor wishes to have left behind by their parents,” Mr. Chhang said. “This diary shows a picture of what daily life was like during the Khmer Rouge.”

Formerly a primary school inspector for the Ministry of Education living in Kompong Chhnang City during Lon Nol’s regime, Poch Yuonly, who was about 50 in 1975, his wife and nine children were evacuated to a collective in Kompong Tralach district on April 19, 1975.

The diary was written toward the end of his life, sometime in mid-1976, and the prose reads like a father speaking out loud to his children—beseeching them to make sure his grandchildren remember him and his life. He regularly refers to himself in the third person simply as “father.”

“This is father’s history. When you receive this diary, you must organize to publish it and distribute it to all your relatives, and to your children and grandchildren so that they will know father,” the diary says at its close.

The diary describes the arduous evacuation of Kompong Chhnang and how the family suffered from the hot weather and lack of food for about 11 days.

Once they arrived at the collective, Poch Yuonly’s wife was sent to work in the rice fields, while the children were put to work as part of the mobile children unit.

“On July 1975, Viseth [my daughter] was sick for about one month. So Nimeth [my son] stole chicken and cassava. His actions brought shame to the family,” Poch Yuonly wrote, adding later that the family ate only porridge for five months at one point. “Everyone was sad and there is always a shortage of everything.”

There were tender moments too.

Vibol, the youngest of the nine children, often worried that his father was going to pass away—he suffered from lung disease and bad stomachaches—and continually pestered him to talk when he was unable to speak or move.

“[Vibol] opened father’s mouth for talking because he did not want me to be silent. He shook my hands and legs when I could not move. Father has great pity for your brother.”

In one excerpt, his wife’s jewelry is exchanged for more medicine for Poch Yuonly, and he pleads with his daughters in his diary to take care of his wife as she is “incomparable to anyone in father’s life.”

“Your mother cries in her heart, in her mind; she cries inside and no one ever sees her cry.”

He begs for death at the end, assuring his daughters that he is unafraid and would like to meet his dead parents and relatives in the afterlife. “Let me die—I cannot live in a world of darkness without news, in a world of ignorance,” Poch Yuonly wrote. “Father saw a lot of the new world and there was enough life lived during my lifetime.”

Ms. Viseth Neary, 50, said Sunday she remembers that period vividly. Her father wrote the diary before he was taken away to a prison in August 1976. The family learned he had died a few months later.

The diary only survived, she explained, because her mother had hidden it. “He wrote to talk about the difficulties in the Pol Pot regime. To let the young generation know,” Ms. Viseth Neary said.