Hok Sothik was 7 years old when the Khmer Rouge seized control of the country in April 1975, he writes in his recently released children’s book, “Sothik.”

Sent to a children’s camp, he longed to return to his parents’ house. So one day, he pretended to be sick and the minute the other children and their guards left for the rice field, he ran home. But he found the house empty, and was soon caught by the Khmer Rouge camp chief.

He was tied to a pole and left there all day without water or food, warned that if he tried to run away, he would be killed.

“I become a hardworking child. I try to do everything expected of me,” he writes. He would spend the whole Khmer Rouge era in boys’ working groups.

Today, Mr. Sothik is the director of Sipar, an organization that has published books in Khmer for children and young adults, and set up libraries in public schools, garment factories and prisons since the early 1990s.

Tonight, he will discuss his own book about a childhood under the Khmer Rouge in a conference at the Institut Francais in Phnom Penh. The book is believed to be the first Khmer Rouge memoir written for children and adolescents.

Published accounts of the Khmer Rouge regime are often filled with information so horrendous that they could traumatize children and young teenagers, and dissuade them from learning about the period, he said last week. “And yet, it’s a very important history chapter for Cambodians.”

So for him, writing the book “was also a matter of duty…sharing those memories of a modest person with young people without traumatizing them,” he said.

An opportunity to do so came in late 2014 when French writer and journalist Marie Desplechin—winner of one of France’s most prestigious literary awards—visited Cambodia as a volunteer for Sipar. Upon hearing Mr. Sothik’s story, she suggested co-authoring the book with him. They worked together in person as well as over video link once Ms. Desplechin returned to Paris, and “Sothik” was released in French by l’ecole des loisirs publishing in Paris last September, and by Sipar in Khmer late last month. Both editions are illustrated by Cambodian-French illustrator Tian.

“It’s the story of a theft, that of Sothik’s childhood,” wrote French newspaper Le Monde in a book review in September. “One listens to the text as if it was a confidence one would not dare interrupt,” wrote Telerama, a French magazine.

Although Mr. Sothik kept young readers in mind as he described events, he tried not to hide facts. He tells of children being woken up, tied and taken away in the middle of the night, never to return. Maybe their parents were Cham Muslim, or else “new people”—that is, educated or city people, he writes.

“At the time, if parents were considered traitors and assassinated, then their children were killed as well,” he says.

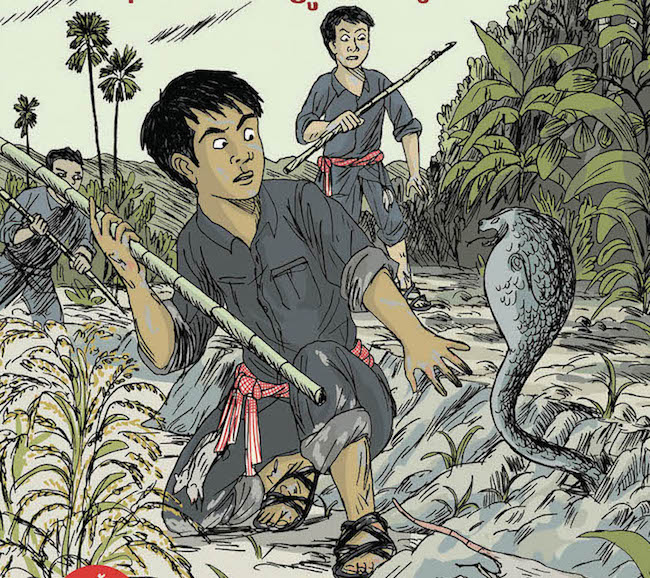

Suffering from poor hygiene and a lack of medicine or basic care, he would wake up with his arms streaked with blood from flea bites, and had thousands of lice crawling in his hair. And there was constant hunger, though that improved when Mr. Sothik was assigned to the children’s rat-catching brigade in the rice fields. During the Khmer Rouge regime, the rule was to denounce each other, but “hunger brought us together,” he writes. The boys cooked and shared some of the rats they caught, as well as the cobras they often found in rat holes and which were tastier. “Grilled, it’s delicious,” he says.

By the time the regime ended in January 1979, he was so traumatized that he refused to go to school because he couldn’t imagine a life other than his last task under the regime—minding cows. He eventually returned to school but had to claim that he was younger than he was to be allowed to enroll.

His immediate family—his father and mother, three brothers and one sister—all survived the regime, but all the aunts and uncles on both sides were killed.

“The memories I have kept are terrifying,” Mr. Sothik writes. “And yet, I had to learn to live with them. Without trying to forget the past, I have to live in the present and for the future. If I manage, maybe it’s because pain, no matter what it is, heals more easily in a child than in an adult. At least, that’s what I tell myself.”

Conference With Author

Where: Institut Francais, #218 Street 184

When: Tonight, 6:30 p.m.

Price: Free