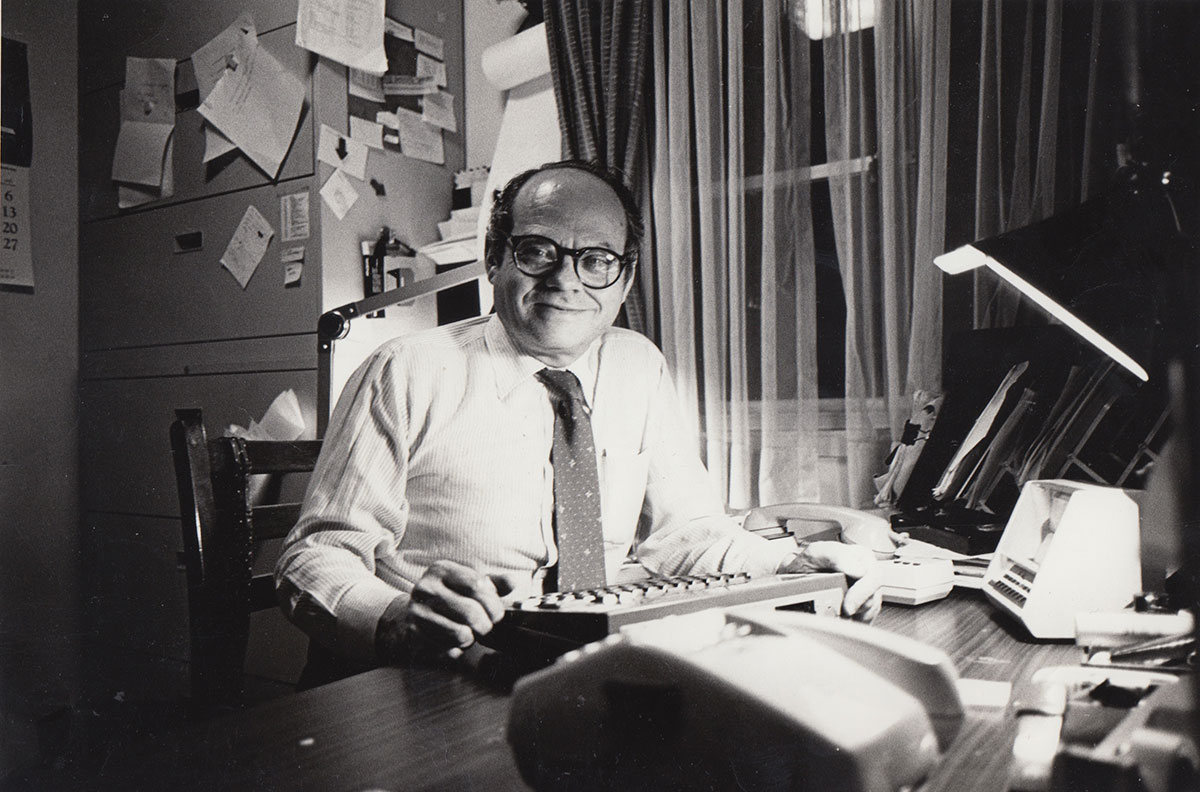

Bernard Krisher, chairman of World Assistance for Cambodia, publisher of The Cambodia Daily and former Newsweek Tokyo bureau chief, died on March 5 at a hospital in Tokyo. He was 87.

His death from heart failure was disclosed by his family following a private burial in New York.

Krisher, who began his career as a foreign correspondent in Japan, dedicated his last three decades to humanitarian work in Cambodia.

The Cambodia Daily, the first of his projects, was the country’s first English-language newspaper, with a mission of reporting “all the news without fear or favor.” The paper was a training ground for Cambodian and expatriate journalists. It published local and international news to readers in Phnom Penh. The regime’s forced closure of the print edition in September 2017 drew international condemnation.

Krisher founded nonprofits that built schools and a hospital. His rural schools project has, to date, built over 560 state schools across every province. While not personally wealthy, Krisher leveraged his rolodex and chutzpah to solicit funds from private donors, and the World and Asian Development banks. Known by many around him as Bernie “Pusher,” he once said, “I remain very New York—quite aggressive, confrontational against authority and establishment.”

The projects that became closest to his heart were the Sihanouk Hospital Center of HOPE that provides free medical care to the poor and an educational center for foster children, orphans and children from remote villages that don’t have a high school.

Krisher moved from New York to Japan in 1962, joining Newsweek as a reporter in the magazine’s Tokyo bureau. He had traveled to the country four years earlier when he was sent to Asia on a six-week reporting assignment by the New York World-Telegram & Sun newspaper, and met his future wife, Akiko, with whom he was married for 58 years until his death. He attributed the works of Lafcadio Hearn with inspiring his interest in Japan and on his decision to live and work there.

Krisher was promoted to become Newsweek’s Tokyo bureau chief in 1967, a position he held for the next 13 years. Krisher interviewed many notable personalities including all Japanese prime ministers and other politicians, business leaders and cultural figures. His most famous interview was a one-on-one exclusive print interview with Emperor Hirohito just before the emperor’s historic visit to the U.S. in 1975.

Krisher’s beat included other parts of Asia, and he traveled widely through parts of Southeast Asia and made frequent trips to South Korea. He succeeded in landing the first exclusive interview with Indonesian President Sukarno in 1964, at a time when Western journalists were on the leader’s blacklist. Sukarno also introduced him to Cambodia’s Prince Norodom Sihanouk, who invited him to Cambodia.

Sihanouk, however, severed ties with the U.S. in 1965, in part over the U.S. government’s refusal to apologize over an article Krisher wrote for Newsweek. Sihanouk eventually restored diplomatic relations with the U.S., and the prince and Krisher subsequently formed a close friendship that led to Krisher’s humanitarian work in the country later in life.

Krisher was also supportive of Kim Dae-jung when the South Korean dissident was a political prisoner. He ran interviews and articles critical of the South Korean government in Newsweek. When Kim became president of the country in 1998, he kept his promise made years ago of granting Krisher the first interview.

After Newsweek, Krisher moved to open the Tokyo bureau for Fortune magazine in 1980 and remained its correspondent until 1984. At the same time, he joined a leading Japanese publisher, Shinchosha, as chief editorial advisor and helped start up Focus, a successful news-oriented photo-weekly, and then set up the Japanese edition of Wired for another publisher, Dohosha. He was also the Far East representative for the MIT Media Lab.

In 1993, Krisher launched The Cambodia Daily to help establish a free press in Cambodia, at the time of the nation’s reconstruction and rehabilitation following the 1991 Paris Peace Agreement concluding two decades of civil war and Sihanouk’s return from exile and instatement as head of state of the country.

Against the advice of many, including Sihanouk who cautioned him that he might be killed, Krisher started the newspaper believing that a democracy needed a free press and told his staff that a paper should be like a gadfly to keep a check on those in power.

Krisher credited the humanitarianism of Albert Schweitzer, the Nobel Peace Prize-winning medical missionary who had built a charity hospital in Africa and whom he met in New York in the 1950s, as his inspiration to embark on his work in Cambodia.

For Krisher, his crowning achievement was the construction in the mid-1990s of the Sihanouk Hospital Center of HOPE in Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh, which provides free medical care to the poor and ran a telemedicine program in remote villages. He was the founder and chairman of the hospital, which was built on land donated by King Sihanouk.

Krisher also made several trips to North Korea in the 1990s to distribute rice and medical supplies to famine victims.

Krisher was born on August 9, 1931, in Frankfurt, Germany, where his mother had gone to give birth close to her parents. The family lived in Leipzig, where his father, a Jew from Poland, owned a fur shop. Krisher and his family fled Germany in 1937 for the Netherlands and France to escape Nazi persecution. He attended two years of elementary school in Paris. When the Germans invaded France, Krisher’s family fled first to the Spanish border seeking onward transit to Portugal. There, Krisher had a fateful encounter on the street with Aristides de Sousa Mendes, the Portuguese consul who issued visas for his family and countless other Jews, against the order of his government.

Krisher’s family fled France via Spain for Portugal where they lived as refugees. They emigrated to the U.S. on the vessel Serpa Pinto, known as the “ship of destiny,” in 1941, arriving through Ellis Island and settling in Queens, New York. Krisher attended New York City public schools, entering elementary school without knowing English, and graduated from Forest Hills High School. He obtained a bachelor’s degree in comparative literature from the city’s Queens College in 1953.

From the time he was a child, Krisher knew that he wanted to be a journalist. When he was 12, he started publishing his own small teenage magazine after the magazines he sold as a delivery boy went bankrupt. He filled his magazine, called Pocket Mirror, which he mimeographed in his Queens apartment, and subsequently Picture Story, with interviews of celebrities such as Babe Ruth, Frank Sinatra and Trygve Lie, the first secretary-general of the United Nations.

He said he learned most of his techniques of journalism during this time. “Persistence, energy, enthusiasm were the key essentials of this profession,” he said, “and the main enemy is cynicism.”

During college, he worked for the New York Herald Tribune as a campus correspondent and copy boy, including at the 1948 and 1952 Democratic National Conventions. He was also an editor at the college student newspaper, The Crown, where, at the height of McCarthyism, he wrote articles critical of the blacklisting of professors branded as communists and being dismissed from their teaching posts. Krisher took heat from the administration, but when he didn’t stop writing the articles, the college president wanted him removed from the newspaper and wrote the editor of the Herald Tribune to have him dismissed from his job there, but the paper refused.

Krisher was drafted into the army in 1953 and stationed for two years in Heidelberg, Germany, as a reporter for the European Stars and Stripes.

He joined the New York World-Telegram & Sun in 1955, first as a reporter, then assistant editor.

From 1961-62, he studied at Columbia University on a Ford Foundation fellowship in advanced international reporting, specializing in Japanese studies at the East Asian Institute. In 1962, he left the World-Telegram & Sun and moved to Japan to join Newsweek.

On his experience escaping the Holocaust, Krisher would say that he never forgot the kindness of strangers who helped his family, and his gratitude inspired him, after building a successful career, to give back to society and help those in need.

Krisher is survived by his wife, his two children and two grandchildren.

One of his last acts was retaining a Japanese law firm to pursue a defamation action against the Atlantic for a misleading profile published in December 2017.