Sothear has been using crystal methamphetamine and heroin for about 15 years but he was never arrested until recently, when he was sent to the Prey Speu detention center in Phnom Penh three times in the past month.

At the time of his first arrest, he was repairing and shining shoes in the capital’s Boeng Keng Kang II commune—earning 30,000 to 40,000 riel, about $7.50 to $10, per day—when he was swept up by authorities who were arresting other drug suspects, he said last week. He didn’t have any drugs in his possession, he added.

Homeless and estranged from his wife and children, Sothear sat cross-legged on a mat inside the Phnom Penh office of Mith Samlanh on Wednesday. The local NGO is one of two that refers addicts to the country’s only methadone clinic at the Khmer-Soviet Friendship Hospital.

Sothear, a pseudonym to protect him from possible repercussions—a condition of anonymity that Mith Samlanh insisted upon before the interview—had been receiving methadone, a heroin substitute used to treat addiction, for the last three years and had decreased how often he injected drugs to two to three times a week.

But inside Prey Speu, he could not receive methadone.

“The withdrawal symptoms started and it made me tired and weak,” said the 40-year-old, clean-shaven and wearing a dark blue Chelsea football club shirt and gray shorts.

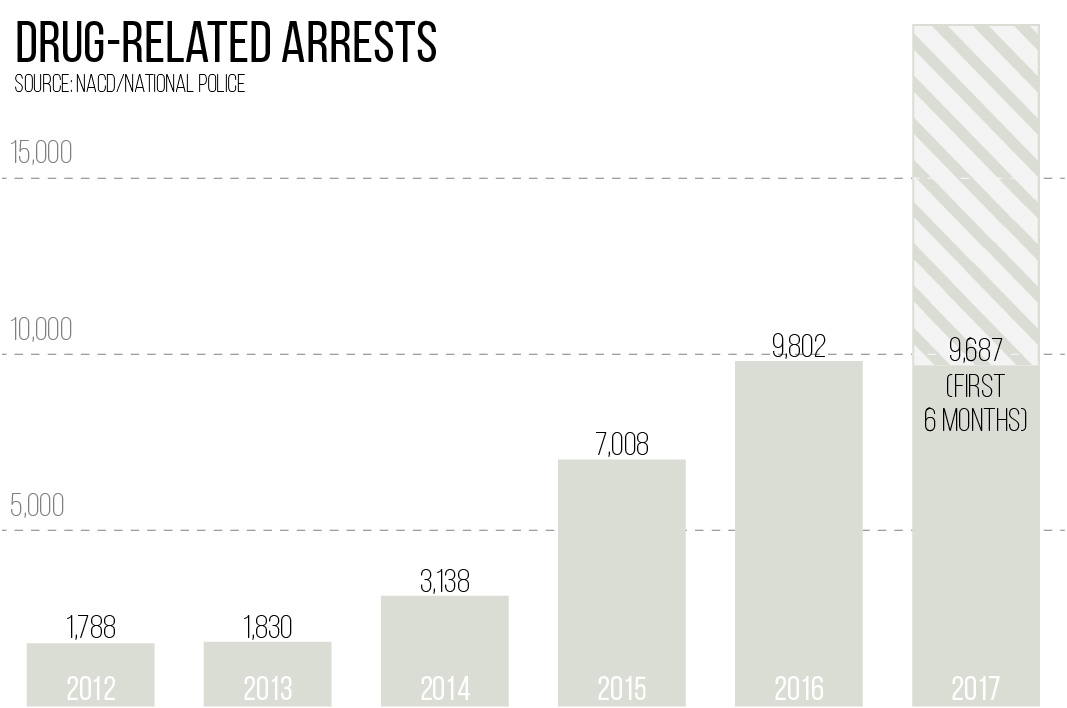

Sothear is one of more than 9,600 people arrested for suspected drug crimes in the government’s anti-drug campaign in the last six months. With about 9,800 people arrested for drug-related offenses in all of last year, the skyrocketing number of people arrested continues a five-year trend of rising arrests.

For now, if you are addicted and arrested over illicit drugs—putting you among the nearly 4,500 suspected users arrested from January 1 to July 1—you will likely end up in a prison, detention center or mandatory, state-run rehabilitation center with little to no chance of getting off drugs, NGOs and observers say.

Like being detained at Prey Speu, compulsory government rehabilitation centers do not offer full access to services that reduce harms associated with drug use, cutting off users from treatment methods like methadone after they’ve begun, which can put them at greater risk of relapse and overdose upon release.

Facing criticism from NGOs and international agencies, the government now says it intends to shift how it treats drug users from mandatory rehabilitation centers to community-based health programs.

In an interview last week, Meas Vyrith, secretary-general of the National Authority for Combating Drugs (NACD), reiterated what he said was the government’s will to change its approach, while also noting some of the challenges it still faced.

While in the past no drug users were entering community-based treatment programs available at 177 sites nationwide on their own initiative, numbers this year have increased as a result of the government spreading awareness during its campaign, General Vyrith said.

“We have noticed that previously no one volunteered to receive [community-based] treatment at the health centers and referral hospitals. We have them, but no one showed up,” Gen. Vyrith said.

But as of last Monday, nearly 1,500 people had voluntarily accessed treatment at the community level, which includes receiving medication and consultations from doctors, since January 1, he said.

Those treated for addiction to methamphetamine, one of the most widely abused drugs in the nation, may be prescribed anti-depression medication, he added.

Community-based treatment, which launched in 2009 in Banteay Meanchey province, allowed users “to receive treatment at health centers voluntarily and close to them,” Gen. Vyrith said, unlike state-run rehab centers, which some considered to be “like detention.”

Still, he said treatment at the local level in which users could live at home had drawbacks, despite pressure to adopt it.

“In order to ease the criticism from some [NGOs], we were trying to expand the community-based drug treatment services, but right now, we are receiving complaints from parents that sending them there and not to [rehab] centers is useless,” he said.

Parents said they were unable to bring their children for daily treatment and addicts would rarely go on their own, he said. Placing them at one of the nation’s eight state-run rehab centers, which have a total capacity of about 8,000 users, was easier for their guardians, he said.

Nearly 2,000 people were sent by their parents, the municipal social affairs department or the Phnom Penh Municipal Court to the state-run rehab center My Opportunity Center in the first six months of this year, City Hall spokesman Met Measpheakdey said on Friday.

More than 600 users were discharged in the same period, Mr. Measpheakdey said.

Treatment included both provision of medicine to treat diseases and addiction, and rehabilitation, such as “education, playing sports and [Buddhist] preaching,” he said.

Gen. Vyrith said the government was still waiting to see how effective community-based treatment was in preventing relapse, but planned to continue adopting the model, despite plans to build a new national drug rehabilitation center in Sihanoukville that would double as a vocational training center.

“The will of the government is to treat drug addiction with community-based drug treatment,” he said.

Voluntary, community-based treatment has been shown to be more effective in rehabilitating drug addicts, according to David Harding, an independent drug specialist who helped start the nation’s first needle-exchange program—unofficially in 2003 and with government authorization the following year.

“Even if community-based treatment is more expensive, it’s actually more cost effective,” he said on Sunday, explaining that if fewer participants relapsed, the government would be making a sound investment.

Four government rehab centers he visited in the midto late-2000s were run by provincial police, military police and the military and were “like a boot camp,” with exercise regimes rather than psychological counseling, Mr. Harding said, adding that he didn’t believe they had changed much since then.

“As far as I’m aware, none of the centers provide any medical-based regimen in order to support people with addiction issues,” he said.

“If people have addiction issues, it’s actually a medical condition,” he added. “Telling people to have the strength of will doesn’t really cut it.”

Today, officials will meet to evaluate the campaign’s outcomes and decide whether they will continue the crackdown, after anti-drug authority leaders last week touted its successes, citing lower overall crimes rates in the first six months of this year compared to the same period last year.

Phnom Penh’s new governor, Khuong Sreng, on Sunday vowed to continue fighting against drugs under his leadership, saying he thought the government should keep up its anti-drug campaign as long as the country still faced drug issues.

A report from the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime released last month noted “steep increases in both the number of drug-related arrests and the number of persons admitted for drug treatment in the country in recent years.”

From 2011 to 2015, the number of admissions into drug treatment increased by almost five times, from 1,011 to 4,959, the report says.

“Methamphetamine, in particular in crystalline form, remains the primary drug of concern in Cambodia,” it says, noting a perceived rise by the NACD in use of both its crystalline and tablet forms from 2011 to 2015.

The government has said a growing number of users and a notable spread in use from cities to rural areas were among the reasons behind the anti-drug campaign’s launch. Cambodians appear to be taking notice of rising drug problems as well.

According to a public survey leaked to reporters last month and apparently commissioned by the ruling CPP, respondents last year ranked drugs and crime as the most important issue in the country that the government should be doing more to address. The issue polled higher in importance than agricultural prices, employment and prosperity, and corruption.

However, a study published in Harm Reduction Journal last month—based on interviews with a few dozen police officers, drug users and NGO field workers—says some in law enforcement lack an understanding about drug treatment services that actually reduce harms caused by drug abuse, like needle-exchange programs.

“The services are still limited and we are urging the government to provide more and better quality of services for both community and closed settings,” Sou Sochenda, a manager at Khana, an HIV prevention and harm reduction organization, said in an email.

Users are not typically able to detox and rehabilitate before they leave state-run rehab centers because of gaps in treatment, Ms. Sochenda said.

In addition, while the government is “really supportive” of treatment for drug users in prisons, rehab centers and community-based programs, it could expand harm reduction services like methadone treatment and needle-exchange programs, she said.

“Counseling, life skills, and vocational training are important for people who use drugs and help rebuild their hope and life,” Ms. Sochenda added.

Sothear, the meth and heroin user, said he would benefit from job skills training and explained that methadone helped him manage his addiction.

After nearly a week in detention at Prey Speu, he said he escaped from the facility by climbing over its fence. The other two times he was detained he said he was sleeping on the street, a regular reason authorities give for locking up homeless people, drug users and beggars.

“When I ran away from Prey Speu, I continued using methadone so I could make a living,” Sothear said.

Now, he fears buying drugs and being swept up in a raid by authorities.

“I’m afraid that they will arrest me again,” he said.