Considering that Sam Rainsy has spent the past 20 years of his life battling Prime Minister Hun Sen and the ruling CPP, the opening scene of his new autobiography is unexpected.

As a 10-year-old boy in 1959, Sam Rainsy watched as police—henchmen during the government of then-head of state Prince Norodom Sihanouk—arrived at his house to arrest his father, the career politician and diplomat Sam Sary. The police carried with them a rope and a stretcher.

“The reason for the stretcher was clear enough. The reason for the rope, I later discovered, was to inflict the same posthumous humiliation as that suffered by Dap Chhuon, a political leader convicted of treason against Sihanouk,” Mr. Rainsy writes.

Dap Chhuon was shot dead and then dragged through the streets by a car with loudspeakers blaring “this is what happens to traitors,” Mr. Rainsy writes.

Foreseeing Prince Sihanouk’s scorn, his father had already fled the country. This is a side of the late King Father Norodom Sihanouk’s period that seems to have been left out of many of the obituaries written about him since his death in October.

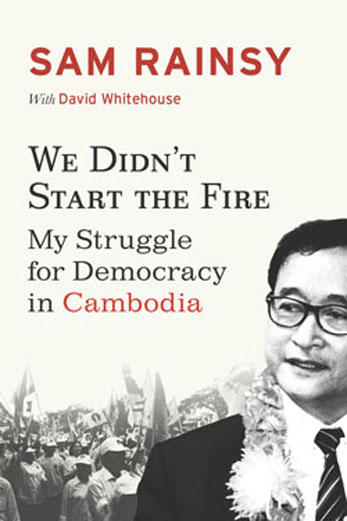

Mr. Rainsy’s autobiography, “We Didn’t Start the Fire: My Struggle for Democracy in Cambodia,” published last month and co-written with British journalist David Whitehouse, is a succinct and often insightful history of Mr. Rainsy’s career in politics, though it gets off to a slow start as he gets bogged down in the details of his childhood.

Trying to frame his upbringing as part of the same political struggle that ultimately led him to be ousted as Cambodia’s Finance Minister in 1994, and began his career as the country’s most prominent voice of opposition to the ruling CPP, Mr. Rainsy comes off as being rather removed from the vast majority of his poverty-stricken countrymen.

Although his father was at times a political opponent of Prince Sihanouk—leaving the Sam family in danger and leading to his mother’s brief imprisonment—Mr. Rainsy’s family was, at the worst of times, only able to eat duck on rare occasions.

“We lived in reduced circumstances,” he writes of the time after his mother was released from prison. “She found us a small house and even managed to buy a Renault 41 car.”

At times Mr. Rainsy might have been better served to avoid his personal life, as his reminiscing tends toward melodrama. In the days following his first meeting with his future wife, opposition parliamentarian Saumura Tioulong, Mr. Rainsy writes that he “dreamed of a freak meteorological accident that would be enough to leave us stranded and cut off from the rest of the world, quite possibly forever.”

But once he gets into politics, an arena in which Mr. Rainsy is undeniably smart—if at times egomaniacal—the book gets interesting.

Mr. Rainsy often suggests that he is, as a bespectacled 64-year-old man, the sole embodiment of the democratic movement in Cambodia. At one point he writes that without him, the fight between the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) and CPP is like a boxing match with only one boxer, a baffling statement given the great, and seemingly successful, efforts that have been made by members of the CNRP in his absence. For what it’s worth, fellow opposition leader Kem Sokha gets only a passing mention in the book.

Nonetheless, his insights into Cambodia’s two decades of bumbling democracy are fascinating, and details of his efforts to oppose the administration of Mr. Hun Sen put into context the importance of his return to the country after four years in self-imposed exile.

Certain sentences capture in a very specific way the reasons for the sad state of democracy in Cambodia. Of Funcinpec’s decision to form a coalition with the CPP in 2003, he says the royalist party chose the benefits of being part of a corrupt government over the “much harder work of building popular political support in the face of intimidation.”

“Patronage in the end involves an abdication of the responsibility for policy,” he writes, summarizing in few words why the CPP has seemingly decided it is unnecessary in this year’s campaign to formulate any coherent plan for Cambodia’s future bar promising more of the same for the country.

And lest one forget that Mr. Rainsy was the country’s most prominent government antagonist during periods when politically motivated violence was commonplace, the book offers some rousing anecdotes about his run-ins with danger.

Amidst demands for a recount of ballots after the 1998 election, Mr. Rainsy and a dozen other SRP members went to the Ministry of Interior, where bags of ballots from across the nation were being kept. While talking with Japanese journalists, a grenade was tossed toward the group and ended up killing one of their drivers.

Undeterred, Mr. Rainsy and members of his entourage stood their ground, but soon found themselves walking at gunpoint to a room in the back of the ministry.

“Seven or eight of us were crammed into the small, dirty cell. I could hear the police discussing how they would execute us and then dispose of our bodies,” he writes.

The second half of “We Didn’t Start the Fire” focuses on how the CPP has failed to serve the population, particularly the poor.

Fighting corruption has been a central theme of Mr. Rainsy’s career, and so it is in his autobiography. “The culture of bribery clearly prevents resources from being allocated in a rational way and deters numerous foreign investors from investing in the country,” he writes. “Cambodia is a mafia state because a group of powerful businessmen, politicians and military men consider themselves to be above the law and operate that way.”

The last chapter, titled “Putting Out the Fire” is Mr. Rainsy’s prescription for getting Cambodia back on the course set out by the Paris Peace Agreements in 1991.

Mr. Rainsy’s plans for the future of his country, however, seem less thorough and thought-out than his criticisms of the current regime.

Recognizing the lack of a developed market for agricultural products, Mr. Rainsy proposes “a price support mechanism to protect them [farmers] from sudden fluctuations in the prices of agricultural goods on which they are heavily dependant,” citing the Thai government’s policies of farming subsidies as an example that Cambodia might follow.

Given recent developments in Thailand, where rice-buying programs have cost the government billions and seen the sacking of its commerce minister, one might question how prudent similar policies would be in Cambodia.

Were he voted into power, Mr. Rainsy writes that his government would provide free health care for all, cancel existing forest concessions to be redistributed to rural populations, immediately move the Khmer Rouge Tribunal outside of Cambodia, impose a wealth tax on the country’s elite, revamp the parliamentary system by having people vote for people rather than parties and, of course, end the culture of corruption by establishing a “genuine” anti-corruption commission.

“We may be judged as a success or failure in government, but our overriding concern is to give the people of Cambodia the right to make that judgment for themselves,” he writes, noting that despite the massive support for Mr. Hun Sen in the past, strongmen can fall fast.

“[Mr. Hun Sen] is the longest serving dictator in the world, but the tide of history is against dictatorship and in favor of democracy. Libya, Yemen and Mali are all recent examples of apparently impregnable dictators who suddenly fell. The world has changed,” he writes.

With Cambodians set to head to the polls next Sunday, it will soon be clear if Cambodia is ready for such change.