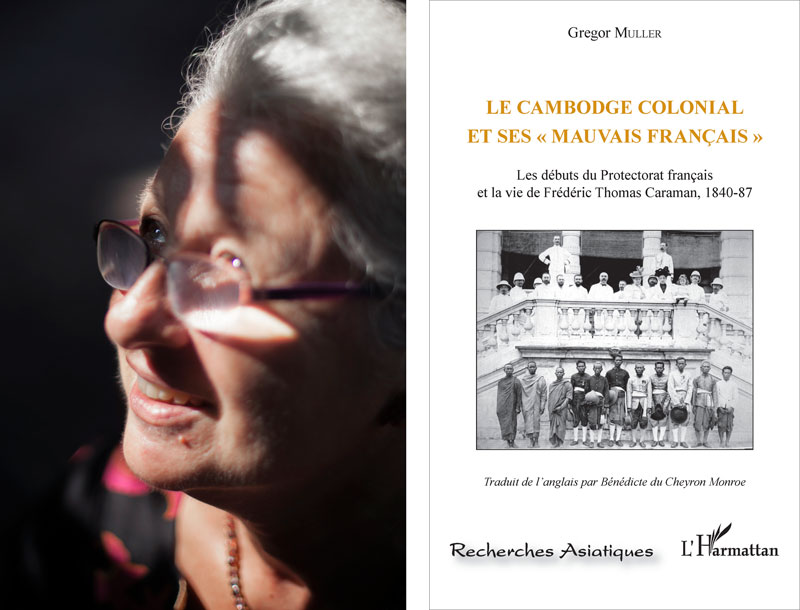

A few years ago, Benedicte du Cheyron Monroe read a book on Cambodia that so intrigued her that she immediately wanted to translate it into French.

Published in English in the late 2000s, Gregor Muller’s book “Colonial Cambodia’s ‘Bad Frenchmen’” addresses issues that, even more than a half-century after the end of French administration in Cambodia, still resonate in France’s psyche, she said.

“I found that the book was analytical and at the same time entertaining,” she said. “It somehow described all aspects of the Protectorate, what one or the other had tried to make happen, and not depicting this as all black or white.

“It always bothers me to see a book such as this one only available in English…that some French people will not be able to appreciate because their English level is limited.”

So Ms. du Cheyron Monroe, a retired French-American economist and translator who lives part time in Phnom Penh, contacted Mr. Muller, who immediately agreed to the project. She translated the book last year and had it reviewed by two French-language proofreaders while the author got in touch with a publisher in Paris. The book was released in September by the publisher L’Harmattan under the title “Le Cambodge colonial et ses ‘mauvais Francais.’”

The book tells the story of Frederic Thomas-Caraman, a Frenchman who came to Cambodia in the 1860s in the hope of making his fortune, but botched every venture he embarked on.

It addresses an issue that historians rarely mention—the fact that the French community in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam in the late 19th century did not comprise a united front—by looking at the lives of marginal figures ranging from translators and drivers to mistresses and small-time businesspeople such as Thomas-Caraman.

“The book presents the advantage of describing intermediary characters, Cambodian or French: colonization’s tools and active participants,” said Philippe Delalande, who oversees L’Harmattan’s publications on Asia. “This study of those modest intermediaries is what sets this book apart.”

The book’s reference to “bad Frenchmen” is what first intrigued Ms. du Cheyron Monroe.

“This expression is a concept that really holds significance” for French people, she said. “Its connotation is fairly specific: people who don’t love their country.”

The term has often been used by people in power to describe those opposing them. During World War II, France’s Vichy regime, which aligned with Nazi Germany, used “bad Frenchmen” to describe not only the underground fighters staging attacks to topple it, but also French people of Jewish ancestry.

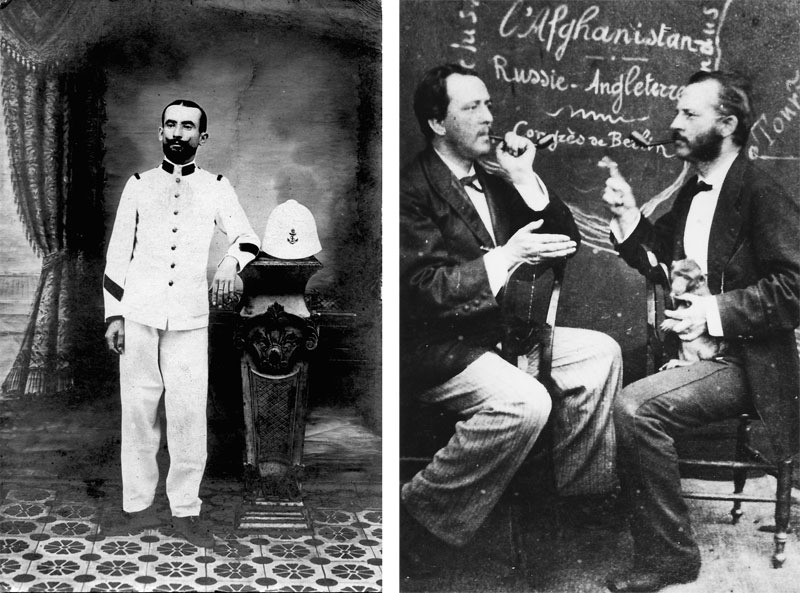

In Indochina, French colonial authorities used the label to refer to freewheeling entrepreneurs such as Thomas-Caraman, who came to Cambodia shortly after King Norodom signed the Protectorate Treaty in 1863.

As policies evolved and French naval authorities were replaced by colonial administrators in the 1880s, French middle-class standards became the norm in Indochina and businesspeople who mixed with Cambodians, or lived with Cambodian women, were frowned upon, Mr. Muller explains in the book.

“Through their ineptitude in business and lack of character, the underlying criticism went, Phnom Penh’s European traders muddled the rigid racial boundaries and social hierarchies without which colonialism was unthinkable,” he writes.

The French authorities excluded from society those who did not behave in a manner expected of a French person in the colonies, Ms. du Cheyron Monroe said.

“They were spoiling the image of the beautiful Frenchman in his sparkling white clothes and colonial hat, and were instead far-from-brilliant, destitute people as, through the good and bad fortunes of their business projects—or commercial booty, since at times it was not even projects—they were going through ups and downs, and mainly downs,” she said.

Mr. Muller is a Swiss historian and archivist who helped set up Cambodia’s National Archives in Phnom Penh in the late 1990s. He has been working for several years for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and is currently the ICRD head of operations in South Sudan.