Like so many Cambodians who lived through the country’s most tragic decades of the 20th century, Chea Vannath emerged from the 1970s and 1980s in a role she never imagined.

A shy and reserved young woman had been transformed into a leader and diplomat who did not hesitate to take action.

As Ms. Vannath explains in her autobiography, “A Cambodian Survivor’s Odyssey,” which was released in English and Khmer in Phnom Penh on Wednesday, her metamorphosis began when she joined a task force at the U.N. refugee center in the Philippines where she and hundreds of Cambodians were awaiting relocation in 1980.

All of the refugees had survived the civil war of the early 1970s and endured the Khmer Rouge’s forced labor camps during the second half of the decade. Then they had fled through war’s front lines along the Thai border after the regime’s defeat.

“I saw the suffering, the misery of the other Cambodian refugees, and I was in a position to help them,” she said Monday in an interview. “I changed myself from a timid woman, an unconcerned woman, to become an active person involved in helping the others…. Like the chrysalis that tries to force itself out of the cocoon to become a butterfly.

“I still had the essence of being timid as a Cambodian woman, not outspoken at all,” she recalled. “So I had to force myself to speak, to stand up on other people’s behalf, because I felt that I had the ability to do that while the others were much more miserable than me. They had nothing.”

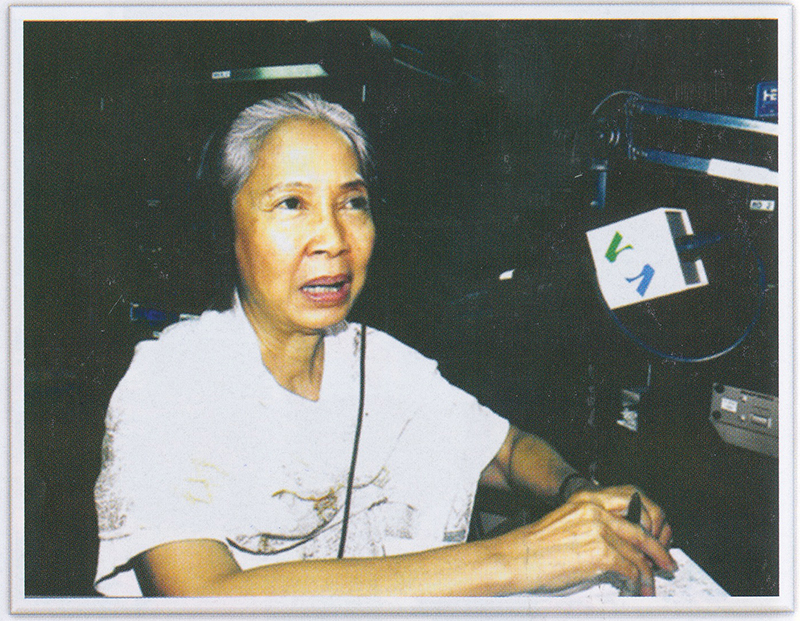

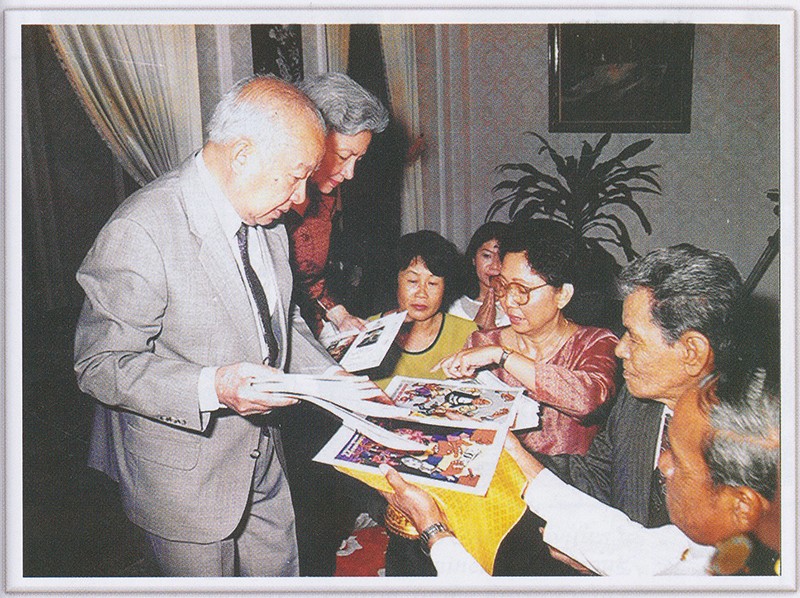

When she returned to Cambodia in the 1990s, Ms. Vannath would take on a similar task, leading an organization that brought political opponents face-to-face in public meetings. The Center for Social Development would play an important role in strengthening freedom of expression in the country through the mid-2000s. A consummate diplomat, Ms. Vannath is still often quoted in the media as a respected political observer.

In her book, which she kept short to make it more accessible to all readers—170 pages in English and 214 pages in Khmer—she describes her years in Khmer Rouge work camps and the difficulties she faced as a refugee. She focuses on facts rather than emotions.

“My story was not the worst one,” she said. Compared to what some Cambodians went through during the Pol Pot regime and afterward, her experience was nothing, she said.

Instead, Ms. Vannath chose to explain how those troubled decades shaped her very nature. At the heart of it all was her faith, she said. Buddhism enabled her to survive.

“Nothing in the world, including humans or non-humans, is permanent,” she said. “The iron is not iron by itself: It’s a combination of small molecules together that keep changing, which is why it rusts. The same with humans. You are born, then you grow, then you decay, then you die. That’s the law of nature. Do you want to protest against that or just cope with it?

“So my nature is to cope with it,” she added. “I had faith and I hung on to that faith.”

Born in 1943, the child of a jewelry-maker in Pursat province, Ms. Vannath as a young woman looked forward to a bright future. She married a medical doctor, Ky Boun Yeap, and earned a diploma in public finance from the Royal School of Administration that might, in another era, have led to a promising career as a public servant.

But along with Cambodia, she was swept into civil war in the early 1970s and ended up in a Khmer Rouge work camp during the Pol Pot regime.

“In the field, during the hottest months, we are always short of drinking water,” she writes. “Too thirsty, I sometimes drink the wasted gray sluggish algae liquid from the hospital sewage canal. I just use my scarf to filter the algae, and drink the liquid.”

From morning to night, on hardly any food, the workers toiled to grow rice. “It takes more than energy to revolt, and we have none,” she writes. “The killing, exhaustion and sleeplessness leave everyone half dead inside.”

Then, in January 1979, the Vietnamese army, assisted by a force of Cambodian defectors, defeated the Khmer Rouge. Ms. Vannath and her family walked back to Phnom Penh, and like the others who clogged the roads, the atrocities and death they witnessed were carved onto their weary faces.

“The scenery looks to me like hundreds of thousands of lost souls…looking for refuge,” she writes.

A year later, revenge murders and random killings were still the rule in Phnom Penh. When armed men arrived to arrest Ms. Vannath’s husband—he was suspected of supporting forces opposing the Vietnamese-backed regime—the couple decided to flee to Thailand. After a long journey, during which they dodged Vietnamese soldiers, thieves and Khmer Rouge forces, they reached the Khao I Dang refugee camp, which was under United Nations supervision.

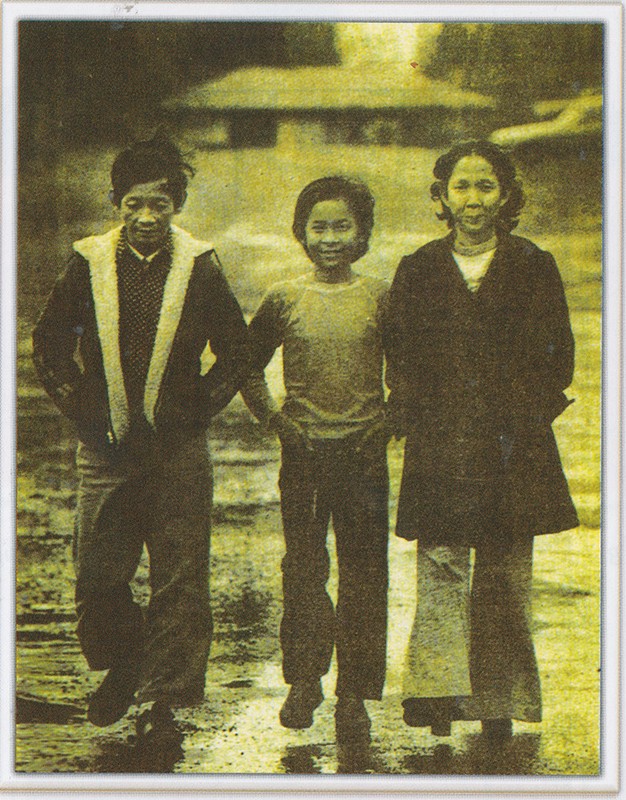

A few months later, the couple and their 13-year-old son, Ky Vannarith, flew to the U.N. Refugee Processing Center in the Philippines. As an elected representative for her camp neighborhood, the only woman chosen for such a role on that committee, Ms. Vannath ended up mediating a dispute involving a Cambodian supply officer accused of corruption. “I surprised even myself,” she writes.

Then and later in the U.S., where her family relocated to near the city of Portland, Oregon, in May 1981, she did not have time to feel sorry for herself.

“I was in the survival mode all the time, a survivor. I did not have time to expect or to grieve or to feel sorrow about anything,” she said. “I could not allow myself to fail. I had to be strong.”

Within two months of moving to Oregon, she had found a secretarial job at a multicultural center and enrolled part-time at Portland Community College, studying finance and accounting.

Her most vivid memory of that period was driving at full speed along a highway in “the most powerful country in the world,” she said.

She was enriched by her new experiences. Some refugees would even say that their flight from the Khmer Rouge, and resettlement, gave ordinary people the chance to experience travel and a lifestyle that only wealthy Cambodians could access in the past, she added.

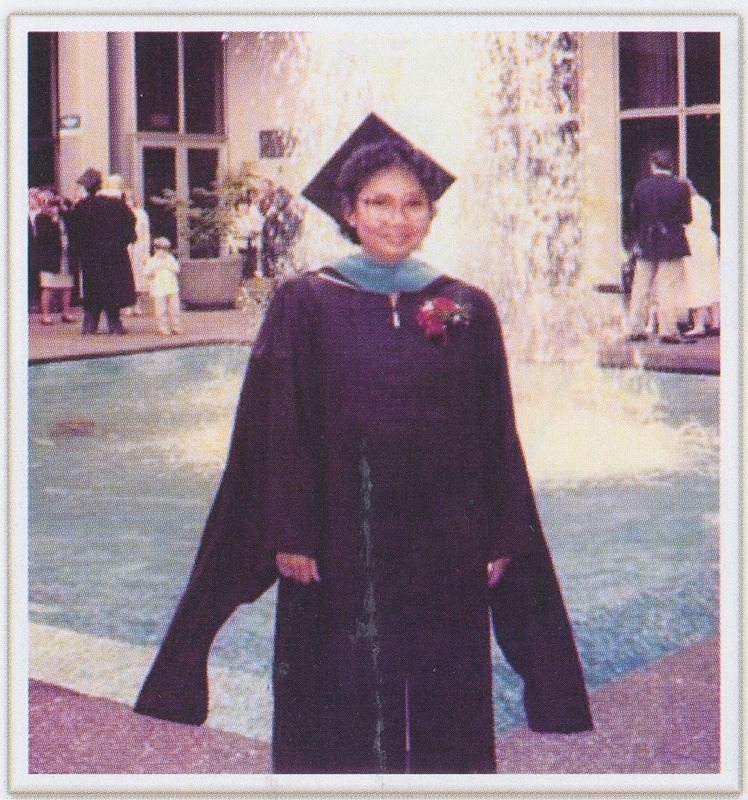

In the 1980s, Ms. Vannath served on the Cambodian National Council, a U.S. organization whose goal was to keep Cambodian culture alive, while working full time and earning a master’s degree in public administration at Portland State University.

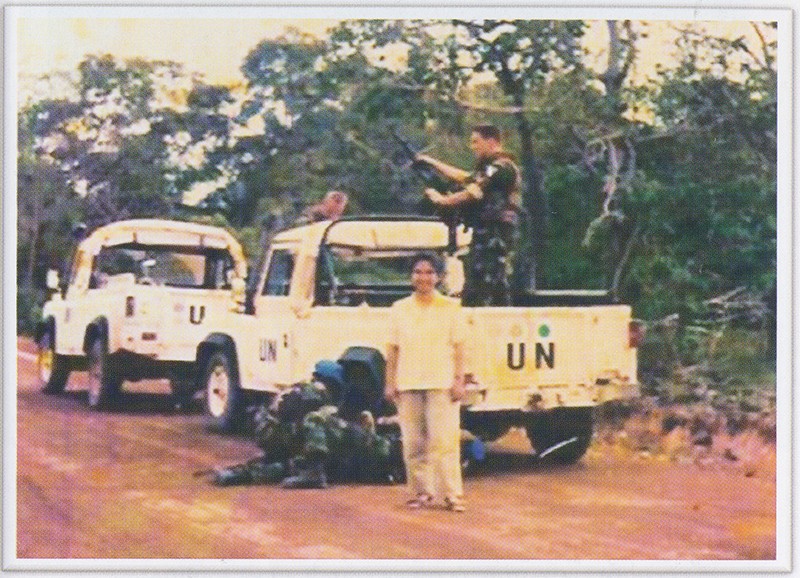

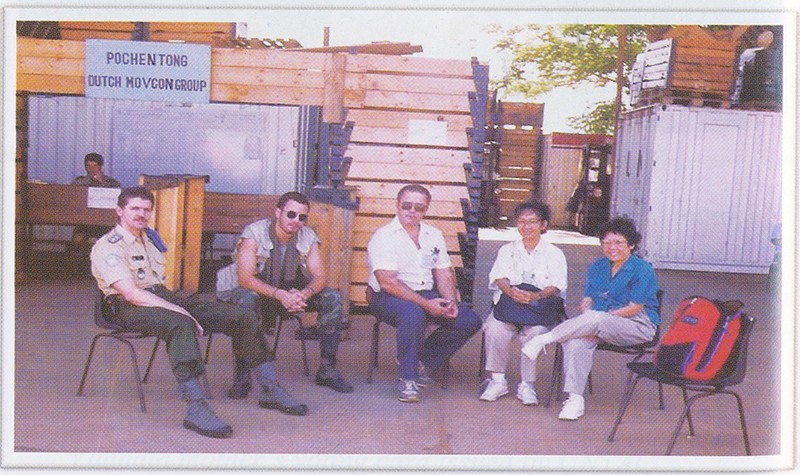

In 1992, she visited Cambodian refugee camps in Thailand. Shortly after, she relocated to Cambodia to serve as a translator for the U.N. Transitional Authority in Cambodia (Untac), which was administering the country and setting up national elections following the signing of the Paris Peace Agreement, which officially put an end to war in Cambodia in 1991.

Ms. Vannath attended meetings held by Yasushi Akashi, the head of Untac. “We used the words ‘interpreters, translators,’ but we were more than that,” she said in an interview. When there were no words in Khmer to render an accurate meaning, “we had to explain the concept,” she recalled.

“In the early 1990s, despite efforts to promote a culture of peace and non-violence, the remnants of post-war violence still widely reflects on the day-to-day aspects of life,” she writes in her book. “Almost every night, I hear the sound of guns firing here and there…. When I go to restaurants, I commonly see people ‘showing their status’ by displaying guns, rifles and hand grenades on the tables.”

Still, Ms. Vannath decided to remain in Cambodia and take a position at The Asia Foundation, an international NGO, in 1994. Then in 1996, she joined the Center for Social Development, eventually becoming its president. Through her work, Ms. Vannath organized public forums and managed to get political enemies, and even former Khmer Rouge and their victims, to interact with each other.

“Being both an activist and a person who accepts the laws of nature is like walking a tightrope: I should not lean too far to either side,” she writes of that time. “Some of my relatives and friends, who are closely related to the ruling party, shy away from me. However, we continue to stand strongly behind our principles and beliefs.”

In January 2006, Ms. Vannath, who was then 62, decided to retire. Unfortunately, the Center for Social Development did not survive her departure. Her successor, Theary Seng, became embroiled in a conflict with the NGO’s board that caused it to falter, then later close.

In the 10 years since, Ms. Vannath has focused on Buddhism, practicing a rigorous form of meditation known as Vipassana. “When you practice Vipassana, you look at the real thing, not because you perceive it to be or you want a thing to be: It’s the truth of nature,” she said.

Her husband died in 2008, and her son still lives in the U.S. with his family, while she has remained in Phnom Penh.

Still, she keeps her finger on the pulse of the political scene in Cambodia and is often interviewed by the media as a commentator. In her book, and in her interviews, she fearlessly outlines the problems the country still faces.

“The lack of respect for the law and the management of society based upon a system of patronage, which leads to weak institutions and widespread corruption, show that Cambodian democracy has not yet matured,” she writes. Economic development in the country must include reducing “the gap between the rich and the poor, urban and rural areas.”

Does the assassination of political analyst and government critic Kem Ley, in a convenience store on July 10, make her wary of commenting on the situation in the country?

“Kem Ley was very aware of what could happen to him, but he could not stop his heart,” she said. “He just made a joke that he would end up in the hospital or at the crematory.”

“When it’s from the heart, you cannot stop it,” Ms. Vannath said. “Whenever it’s from the heart, there’s no good reason to stop…no matter the risk.”

“A Cambodian Survivor’s Odyssey” was published by the Forum Civil Peace Service (forumZFD), Germany.