In the late 9th century, King Yasovarman I ascended to the throne of the Khmer kingdom with ambitious plans for his realm.

First, he moved his capital from Roluos, east of what is now Siem Reap City, to a site dominated by a hill. On top of it, he built the temple of Phnom Bakheng, founding the city that would serve as the capital of the Khmer empire for the next 500 years. He called it Yasodharapura—the city of Yasovarman. It is known today as Angkor.

But this king’s vision went further than a new capital. He was thinking in terms of an empire.

“From his reign on, that is, the start of the 9th century, there was a determination on the part of Angkor’s monarchs to dominate this Khmer universe,” said French archaeologist and epigraphist Dominique Soutif.

Yasovarman I tightened his control over the multiple small kingdoms that had been brought together to form Angkor, and extended his lands from northeastern Thailand and southern Laos to southern Vietnam.

As part of demarcating his territory, Yasovarman I went about creating 100 monasteries, or ashrama, along the empire’s roads. Mr. Soutif, a researcher with the Ecole francaise d’Extreme-Orient—a French government research institution that focuses on Asia—is in the midst of a long-term project to locate those monasteries and excavate the sites, working along with French researcher Julia Esteve and Cambodian archaeologist Chea Socheat.

“Here and there, they would set up a certain number of buildings that would establish royal power by always erecting them according to the same plans, the same model and with [stone] inscriptions stating the king’s wishes as to endowments granted to these sanctuaries, and damning anyone who would steal from those royal foundations,” Mr. Soutif explained.

“This truly was a political and religious branding of the site, and therefore of the territory controlled by the king.”

Leaving no doubt that these institutions were under royal authority, an inscription at two major monasteries located on the Mekong River in Southern Laos stated that their personnel were strictly working for the religious community and that under no circumstances were the monasteries to be used by the local leaders. This made it seem as if the king had felt the need to reassert his power in that remote part of the empire, Mr. Soutif said.

According to Angkorian-era stone inscriptions, Yasovarman I set up 100 monasteries similar to the ones found in Southern Laos.

“They basically were the equivalent of today’s pagodas,” Mr. Soutif said. “Monks or religious figures lived there or would go on a retreat there at some times of the year.

“But this was also a refuge, meaning that if you were being pursued, you could hide there. And they were teaching institutions where students lived.”

Since they housed large communities that required food and other necessities, these monasteries stimulated agricultural, arts and handicrafts activities, turning them into major economic centers, he said.

The inscriptions found at the monasteries also state that they cared for the poor and the sick, according to Ms. Esteve, a French specialist in Southeast Asian religions based at the College of Religious Studies at Mahidol University in Bangkok. One inscription reads, “Ordinary people without exception, young boys, the old, the sickly, the poor, the abandoned shall be well cared for with food, medicine and other necessities.”

However, this care applied only to men, Ms. Esteve said. Women were usually not allowed into monasteries, although female members of the royal family and the aristocracy could visit.

“This tends to show that those religious orders consisted exclusively of men. There was, however, a staff of women,” she said.

Locating these monasteries, which were built about 1,200 years ago, has been no small task for the three researchers, especially since some of the structures were built with wood, which would have disintegrated long ago.

The three researchers have been able to ascertain that these institutions still existed toward the turn of the 13th century. But it is still unclear whether most of them continued to function as monasteries, were converted for other uses or were abandoned altogether.

In some cases, the original structures may have been replaced by pagodas because the site would have been considered sacred, Mr. Soutif said. This is true of Phnom Preah Bat in Kompong Cham province. There is an inscription that confirms there was a monastery on top of that mountain, but no trace of it remains, having long ago been replaced by a pagoda.

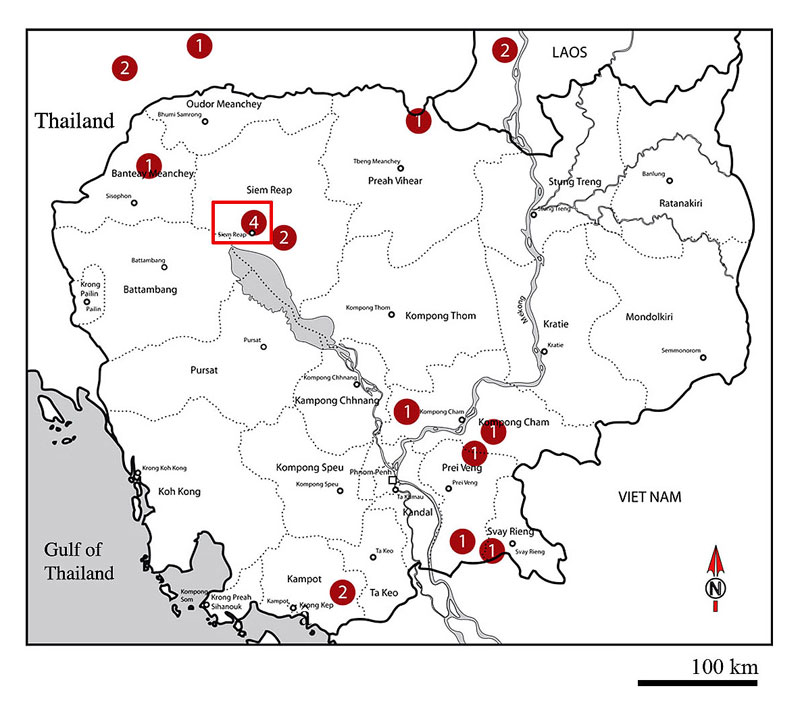

So far, such stone inscriptions have proven the existence of four monasteries in the city of Angkor and 17 in the rest of the country. The researchers have excavated the sites at Angkor—Prasat Komnap South and Prasat Komnap North, Prasat Ong Mong and Prei Prasat—and found that all of them have distinctive layouts, being rectangular sites running east-west and spanning an area of 375 meters by 150 meters. Each of the monasteries also features a building that is around 25 meters long, but very narrow.

The researchers eventually hope to use their knowledge of these structures to identify other links in Yasovarman’s chain of ashramas, finding other sites whose buildings were set up in the specific layout used for those monasteries, Mr. Soutif said.

The four monasteries at Angkor played a different role than those in the provinces, Ms. Esteve said. “We can assume that those institutions were major training centers,” she said. “We believe they were very dynamic intellectual centers.”

Of the four ashrama at Angkor, one was Buddhist and the other three Hindu, with two dedicated to Shiva and one to Vishnu. People of either faith were tolerated under Yasovarman’s rule, even though a monastery would have adopted one faith or the other.

“Sivaism was the religion of the power under King Yasovarman I, which did not mean that he could not protect others, which was no problem in Cambodia at the time,” Mr. Soutif said. Jayavarman VII in the 12th century became a fervent Buddhist, but he also endowed statues at Hindu sites. It’s only during a little-known period called the Sivaist reaction toward the 13th and 14th centuries that religious intolerance appeared in the country, Mr. Soutif added.

The three researchers intend to complete their excavations of the four ashrama at Angkor next year with support from researchers from several countries and the Apsara Authority, the Cambodian government agency that manages Angkor Park.

Mr. Socheat, who has been studying at the Universite Paris-Sorbonne, is expected to submit his Ph.D. thesis focusing on the Buddhist ashrama of Angkor within the next two years. Then he and his two colleagues intend to excavate two sites at remote locations in Preah Vihear province in 2017 and 2018 in cooperation with the Ministry of Culture.

This will help to ascertain the extent of the Khmer territory in the 9th century. The notion of borders at the time was far more nebulous than it is now, and border demarcations were largely restricted to roads, rivers, lakes and areas where there was known human activity. The deep jungle and uncharted territory was of little to no importance to people living at the time, Mr. Soutif said, so a drawing of the Khmer kingdom would have consisted of Angkor in the center, with roads spreading radially in all directions.

This is why staking a claim along the road network was crucial in defining Angkor’s territory, Mr. Soutif said.

While Yasovarman I’s monasteries played both a religious and social role in society, the king’s political motives could not be ignored, Ms. Esteve noted.

“Politics and religion were intimately linked, as it is sometimes the case even today,” she added.