Even within the context of the unimaginable atrocities committed during Pol Pot’s rule, Cambodia’s Chinese community endured some of the greatest losses under the ultra-communist regime.

Out of a population of 430,000 ethnic Chinese inside the country when the Khmer Rouge took power in 1975, historians say about half had perished by the time the regime was overthrown less than four years later—dead from disease, hunger, exhaustion or execution.

“Democratic Kampuchea was the worst disaster ever to befall any ethnic Chinese community in Southeast Asia,” prominent academic Ben Kiernan writes in his book, “The Pol Pot Regime.”

The deaths, by proportion, were higher even than the 36 percent of the 250,000 ethnic Cham Muslims and 21 percent of Cambodia’s native Khmer who lost their lives during the regime, according to prevailing estimates.

Yet a question persists: Was it genocide?

Motives For Murder

The reasons for the loss of so many Chinese lives at the hands of the regime is still debated among historians and academics.

Some argue that a disproportionate number of Chinese died because they were seen as urbanites, and therefore enemies of the revolution. Others contend that the group was directly targeted because of their ethnicity.

The tragedies that befell the Chinese during Democratic Kampuchea have been omitted from the genocide charges at the Khmer Rouge tribunal, where the regime’s second-in-command Nuon Chea and head of state Khieu Samphan are on trial.

While dozens of witnesses have taken the stand to recount tales of massacres and desecration of culture of Cham Muslims and ethnic Vietnamese, the horrors the Chinese faced have gone almost completely undocumented at the tribunal.

But 81-year-old Kang Heng remembers.

While trudging through another grueling day of labor in the rice paddies of Kampot province during the Khmer Rouge years, Ms. Heng witnessed soldiers tying up a group of her neighbors, mostly Chinese-Cambodians, and marching them away.

“I saw some people led away for reeducation. I didn’t see them killed, but I saw them tied up and taken away,” Ms. Heng recalled during an interview at a Phnom Penh restaurant last month.

She never saw the villagers again.

While sympathetic to their fates, Ms. Heng, whose grandparents were half Chinese, doesn’t believe the villagers were singled out because of their ethnic background. Many Chinese were targeted because they were wealthy, she said, and therefore seen as oppressors of the peasantry.

“The group of Chinese were killed because they were rich before the regime,” she said. “It wasn’t because of their ethnicity.”

Ms. Heng thinks she survived because she worked especially hard in the fields and because her family only ran a small rural shop before 1975. But the Khmer Rouge were capricious, she admitted, and her sister was murdered by a local cadre who “randomly accused her” of a crime.

Unwelcome Urbanites

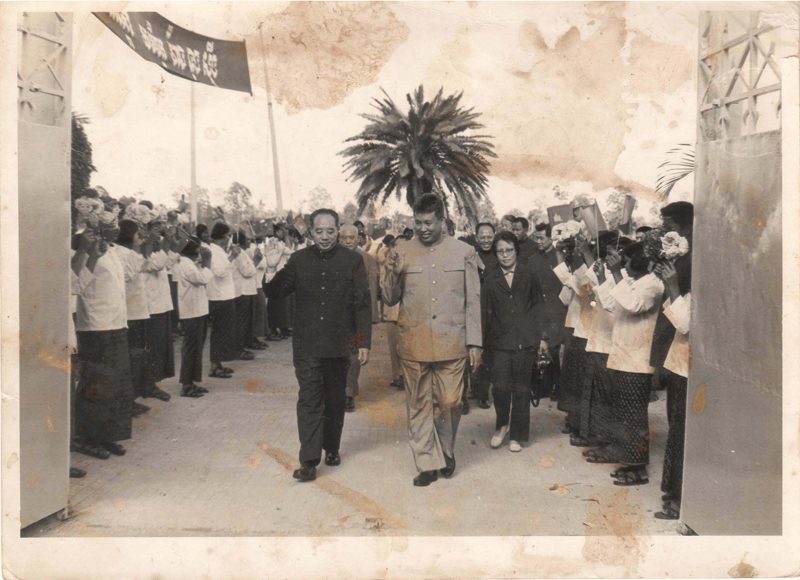

China was the Khmer Rouge’s strongest ally. Chairman Mao Zedong and his successors sent large numbers of Chinese technical advisers to assist the Pol Pot regime. Ideologically, there were clear similarities between the disastrous agrarian socialist experiments inflicted on both countries, and the Khmer Rouge are often referred to as “ultra-Maoist.”

This appeared, however, to do few favors for the ethnic Chinese living inside the country. No one argues that thousands upon thousands of them died during the Khmer Rouge years. Rather, the main issue of contention by those seeking justice for the dead is whether the regime actively targeted the group because of their ethnicity or their social circumstances.

Were they purged because of their clan or because they were urbanites—representative of a wealthy, educated class and therefore enemies of the revolution? The distinction matters greatly in any legal discussion of genocide, yet even the experts disagree.

To many, the term genocide is synonymous with mass murder. The U.N. Genocide Convention, however, defines the crime as “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” Economic and political purges are not covered by the convention because Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin had those removed from the convention’s final draft in 1948.

Chan Sambath, a Sino-Khmer academic whose mother was murdered by the Khmer Rouge and has since researched the treatment of the Chinese during the regime, remembered his people being singled out by cadres in Kompong Chhnang province as a young child.

“They sent us to child camps and they distinguished Chinese children, Cambodian children and Vietnamese children,” Mr. Sambath said last month in Phnom Penh. “They treated us different from the others—less food, more hours to work. They would say, ‘You are Chinese. You used to have a full fridge of food and now it’s time for you.”

Mr. Sambath believes they were targeted because of their status as urbanites, and that many died as they struggled with a life of hard labor after being uprooted from the city.

“A lot of Chinese at that time didn’t know how to speak Khmer very well. It was very hard to beg people for food. Even though everyone is ‘equal,’ they don’t understand you because your Khmer is not clear, right?” he said.

“They killed them because their class was different. They killed them because they were urban. They killed them because they wanted to retaliate,” he said. “They hated that the Chinese controlled all economics at that time. Lastly, the Chinese were a little bit stubborn and they did not really work as hard as the farmers and other ethnics like Cham or Vietnamese.”

Mr. Sambath’s theory—the Chinese were targeted because they were wealthy and educated—is often supported by Khmer Rouge academics.

In his book about Pol Pot, Mr. Kiernan writes that there was “no noticeable racialist vendetta against people of Chinese origin,” but that the group was targeted as they were perceived as “the archetypal city dwellers.”

Elizabeth Becker, a veteran U.S. reporter who interviewed Pol Pot and authored “When The War Was Over,” said the Chinese were targeted due to their socioeconomic status prior to the revolution.

“The ethnic Chinese were condemned as ‘imperialists,’ as members of the old ‘comprador class’ in party rhetoric. Informally, they were condemned as ‘chalk face’ or ‘white face,’” Ms. Becker said in an email.

“Members of the Chinese minority had been envied and feared for their business prowess in the ‘old society’ and largely lived within their own section of Phnom Penh, the Chinese quartier. Many barely spoke Khmer. After 1975, they were thrown out of the city and sent to the countryside. Many were killed off right away,” she added.

Ethnic Cleansing

But others contend that focusing on social or economic divisions leads to a facile explanation for treatment of the Chinese. Penny Edwards, a British historian and professor at the University of California at Berkeley, said she had gathered during her research clear examples of Chinese being targeted purely for their membership in an ethnic group.

She specifically cited the account of 29 families who were buried alive in what was then Kompong Cham province.

“The stories I heard in the 1990s gave me grounds to believe that a disproportionate number of Chinese, across a social spectrum, including rural and urban Chinese, had been targeted for punishment and execution because of the expression of ‘ethnical’ and ‘racial’ membership of a group through such markers as Chinese language use,” Ms. Edwards said in an email.

“The worst story I heard was of 29 Chinese who were rounded up and buried alive in Chhup, in the grounds of a colonial villa. I heard it from people who had witnessed it, and who we interviewed independently of each other in Chhup,” she said.

“The massacre was triggered by two Khmer Rouge cadres overhearing two elderly Chinese women talking Chinese to each other,” she added.

Ms. Edwards said the branding of the country’s Chinese as wealthy urbanites in trying to explain why they were targeted has perpetuated the same stereotype that led to the Chinese being targeted during Democratic Kampuchea.

“Immediately after the DK, respected journalists and scholars made sweeping statements to the effect that Chinese died in greater numbers because (a) they were targeted on class grounds and (b) they were more likely to die because they were soft-skinned city people who were not used to rough treatment and peasant labor,” Ms. Edwards said.

“Those statements contain their own inbuilt prejudices about Chinese in Southeast Asia, and recycle the stereotypes which I believe led to the disproportionate targeting of Chinese: namely, that all Chinese were wealthy. Once those statements were published they gained their own narrative traction, and were seldom questioned.”

The complexity of the situation was compounded even further, the historian said, by campaigns by Mao Zedong’s officials to target Chinese who had lived overseas and returned home.

“The Khmer Rouge leadership might have picked up on this when they visited China in the early 1970s, and oral history and survivor memoirs indicate that some Chinese technical experts posted to Cambodia by the Chinese government in the Khmer Rouge period also brought those perspectives and prejudices with them,” she said.

Defining Genocide

In weighing whether the ethnic Chinese population in Cambodia were victims of genocide, answering the question of why they died in such high numbers is beside the point, some argue. Mr. Kiernan writes that the treatment of the Chinese “could be construed as genocide,” despite his belief that they were targeted on class and economic grounds.

Gregory Stanton, the president of Genocide Watch, who also founded the Cambodian Genocide Project in 1981, said debates over why the Chinese were targeted could have muddied efforts to prosecute anyone for their murders.

“Prosecutors would have to prove that the Chinese were killed because of their race to prove charges of genocide against Chinese people by the Khmer Rouge leaders. So the other two reasons they were killed (Marxist economic class enemy doctrine, and because they were urbanites) would actually complicate the prosecution, and ironically could be used by the defense to counter charges of genocide,” Mr. Stanton said.

“Cham and Vietnamese lived in rural areas. They were not landowners or merchants. So neither of the other two reasons why Chinese were targeted applies to them. That makes it easier to prove that they were persecuted and killed because of their religion, ethnicity, race, and nationality,” he said.

Craig Etcheson, a prominent researcher who served as chief of investigations in the Office of the Co-Prosecutors at the Khmer Rouge tribunal, said he believed the Chinese were perceived as “class enemies” and rejected the suggestion that their treatment amounted to genocide.

“I do not think there is a good case to be made that the ethnic Chinese were targeted for genocide,” Mr. Etcheson said in an email. “The Cham and the Vietnamese were targeted because of who they were; the Chinese were targeted because of what they were perceived to be: shopkeepers, merchants, and bankers.”

Identifying the distinction between motive and intent is something “that a lot of people don’t get,” Mr. Etcheson said.

“I think what we’ve got here is that the Chinese weren’t targeted because they were Chinese, but because they were bourgeoisie, and hence an economic group, which is not among the types of groups protected under the genocide convention. If you were a poor Chinese peasant, you would not have been targeted.”

Mr. Sambath, the Sino-Khmer academic, who now splits his time between Phnom Penh and Canada, believes the tribunal dodged the Chinese question. The court—plagued with accusations of political interference—likely did so because of the increasingly close ties between the governments of Cambodia and China, he said.

“They don’t want to bring that issue to the court, this is my opinion. The Cambodian government, they might bring that issue and it might hurt the Chinese more because there is a very close relationship between Cambodia and China,” Mr. Sambath said.

“Why did the Cambodian people not want to protect Chinese or why did the Chinese not protect Chinese in Cambodia? They don’t want to bring that issue to the public.”

(Additional reporting by Chhorn Phearun)