For millennia, as Cambodians embraced new religions, they have also habitually clung on to some of their old beliefs and practices.

“The idea is that a religion immediately takes effect, which is why one must get all deities on one’s side,” said French historian Alain Forest of the tendency to welcome elements of different religions.

Historically, kings and political leaders have also taken quite a practical approach. “The idea behind religion is to accumulate ‘magic’ for power,” he said.

Mr. Forest’s recent book “Histoire religieuse du Cambodge” (Religious History of Cambodia) tells the story of when and why Cambodians came to adopt diverse religions.

Released by the Parisian publisher Les Indes savantes, this 267-page book places religious currents within the twists and turns of Cambodia’s development, providing an overview of the country’s history in the process. It is based on Mr. Forest’s field research, French and Cambodian archives, and major relevant studies published since the late 19th century.

The work starts with a description of the Khmer people more than 2,000 years ago. As they began to farm the land, they developed myths and legends such as those of the “Lady of the Rice” and the “Crocodile” to explain the birth of their country and natural phenomena. The ritual during which the teeth of teenage boys were lacquered black—still practiced as recently as the 20th century—originated in that era, its goal being to make young men aware of their humanity by making their teeth unlike the white ones of crocodiles and other predators, the book explains.

As maritime trade routes developed between the Middle East, China and India around the first century, ports of call appeared along the coast of the Gulf of Thailand as some Khmer leaders were asserting their power over portions of southern Cambodia.

“The coast between Kampot and Da Nang became required ports of calls between the Malaysian peninsula, China and India, if only for ships to replenish their water supplies,” Mr. Forest writes.

These trading routes, which prompted exchanges and intermarriages between royal families in the region also brought Brahmanism to Cambodia. The extent of the relationship is illustrated by the fact that a Cambodian king in the fourth century was named Kaundinya after the Brahman hero of an Indian epic tale.

Brahman priests retained a powerful position at court throughout much of the Angkorian period, while some kings would opt for Hinduism—favoring the cult of Shiva or Vishnu—or, in the case of King Jayavarman VII, establish Buddhism.

Although kings in Angkorian times were not considered deities, Brahman rites established them as being chosen by the gods, according to Mr. Forest. The status of kings would change when the country fully embraced Theravada Buddhism in the 1400s: From then on, they would be known as having been chosen by men.

“It is nearly certain that the development of Buddhism…reflected an aspiration and true evolution toward a change in society in which social structures would be less inexorably set and relations of ascendancy would be more ‘humanized,’” Mr. Forest writes.

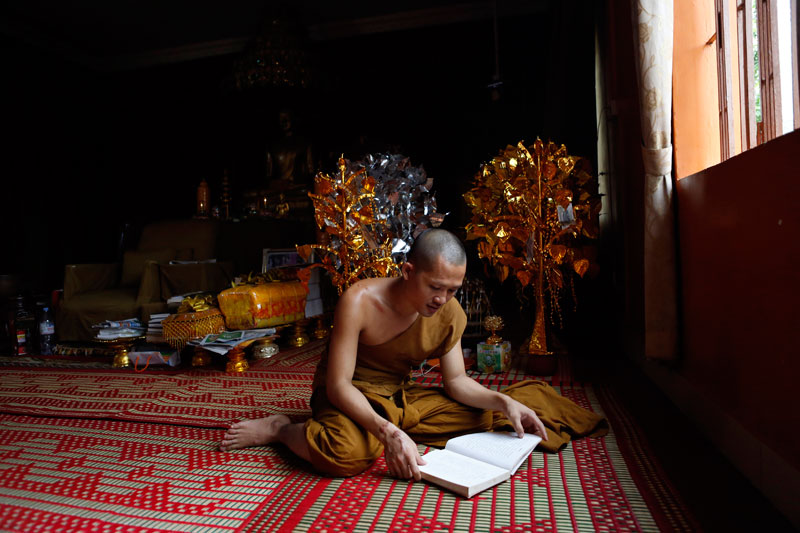

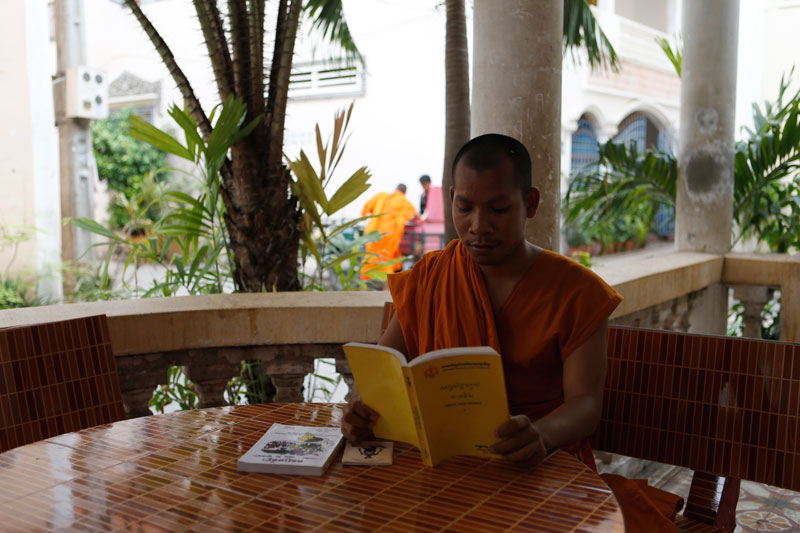

One crucial aspect of Buddhism that would change society is that, unlike Brahman priests who came from elite families, young men of any background could be Buddhist monks, he adds.

The Cambodian retreat from Angkor in the mid-15th century would be the start of uncertain times as successive kings moved their capital from city to city and people had to reinvent their agricultural methods to adapt to new regions.

The advent of King Ang Chan, who set his capital at Longvek in the first part of the 16th century, marked a return to some stability. During that period, prehistoric beliefs and notions of spirits inhabiting places were combined with Buddhism, the book reads.

Stability came to an end in 1594 ,when the Thais attacked and ransacked Longvek. This ushered in a dark era of nearly two centuries during which Cambodia would be in a constant state of war as princes sought support from either Vietnam or Thailand to claim the throne.

While princes fared fairly well, this was not the case for the people: The Vietnamese imposed their administration and methods on populations under their control, while the Thais emptied parts of Cambodia and brought back to Thailand thousands of slaves, Mr. Forest writes.

Thai Buddhism was then experiencing a golden period, with its influence radiating across the region. A small group of elite Cambodian princes and monks went to study at Thai monasteries.

It was to curb this Thai influence, which the French administration felt might extend to politics, that would lead to the creation of the Buddhist Institute in the 1920s in Phnom Penh and encourage advanced training for Cambodian monks in the country.

By the time King Ang Duong acceded to the throne in 1845, the country was in a poor state, a witness quoted in the book states. “Poverty prevailed in the country…. Farmers deserted villages because they were afraid of the Vietnamese and the Siamese who stole their crops.”

Ang Duong launched a series of programs to remedy the situation. This included rebuilding monasteries that had been destroyed and supporting the development of Buddhist institutions. Fear of the country’s more powerful neighbors would drive King Norodom to sign the Protectorate Treaty with France in 1863.

In the 1800s, a new Buddhist sect, the Thommayut (renewed law), appeared in the country, preaching a return to the original Theravada rule. When King Norodom moved his capital from Oudong to Phnom Penh in 1866, this sect settled at Wat Botum pagoda, while the traditional sect Mohanikay came to Wat Ounalom. These pagodas remain the seat of the respective sects today.

In the 20th century, Buddhist monks had access to education programs supported by the French, one outcome being that some Buddhist monks were among the first Cambodian intellectuals to call for independence from France. Monks such as Chuon Nath and Huot Tat—two venerables who dominated Cambodian Buddhism until their deaths in 1968 and 1975 respectively—even studied Sanskrit with French scholars in Hanoi.

Cambodia gained its independence in 1953 and, until about 1967, Buddhist monasteries flourished. The growing opposition against the government of Prince Norodom Sihanouk in the late 1960s reached pagodas.

“Repression of those opposing [the regime] on the pretext of pursuing the Khmer Rouge did not spare pagodas where investigations increased and where, when suspected, some monks were brutally defrocked so they could be immediately arrested,” the book reads.

During the Khmer Rouge period, some leading monks were killed while others were sent to join the population.

Following the defeat of the Pol Pot regime in January 1979, the Mohanikay sect was reinstated with Tep Vong heading it. The Thommayut order, considered too elitist, was prohibited; it would be reinstated after the signing of the Paris Peace Agreement in 1991.

Across the centuries, the notion of monks and followers being linked through the exchange of donations, which provides followers with merits ensuring them a bright future in their next lives, has been one of the main religious features in Cambodian society, Mr. Forest explained.

Today, this had led to Cambodians living in the country or abroad funding the construction of new buildings at their favorite pagodas. Such projects often are done with little or no understanding of actual needs at pagodas or the historical, cultural or artistic value of what will be destroyed and what will replace it, he said.

In addition to wishing to bank merits, donors often mean to honor those who perished during the two decades of war and conflicts in the country. “In short, Buddhism is becoming a religion of the dead and it may be this trait that is destined to characterize it in the future, to determine its evolution and assure its permanence,” Mr. Forest writes.

As Cambodia’s religious institutions enter the 21st century, “Today’s true challenges reside in changes that take place in society: the emergence of a Westernized and then globalized society and of an urban society or at least the end of rural isolation with the multiform development of communication means,” he writes.

One other challenge for Buddhism is reaching today’s youth, Mr. Forest said in interview. Although young people follow rites, there is no knowing whether this is done out of any religious conviction or simply to respect their parents and families, he said.

Born in 1946, Mr. Forest lived in Cambodia in the mid-1960s in a Catholic community along the Mekong River. He is a university lecturer, researcher and book editor who oversaw collections on Asian studies and in 1980 published a major study on the French administration in Cambodia between 1897 to 1920.

Mr. Forest stopped studying Cambodia for a time, as all but one person he had known during his time in the country perished during the years of war and conflicts. It was only in 1992 that he published a study on Cambodia’s protector spirits, the “neak ta.” He has since overseen the publication of works on Cambodia while pursuing research.

Based in France, he comes to Cambodia several times a year to teach at the Royal University of Fine Arts.