Drones may have drawn the ire of authorities in Phnom Penh, but a new company helmed by the prime minister’s son-in-law and a globetrotting Texan pilot wants to put them to work on plantations, timber farms and mining sites.

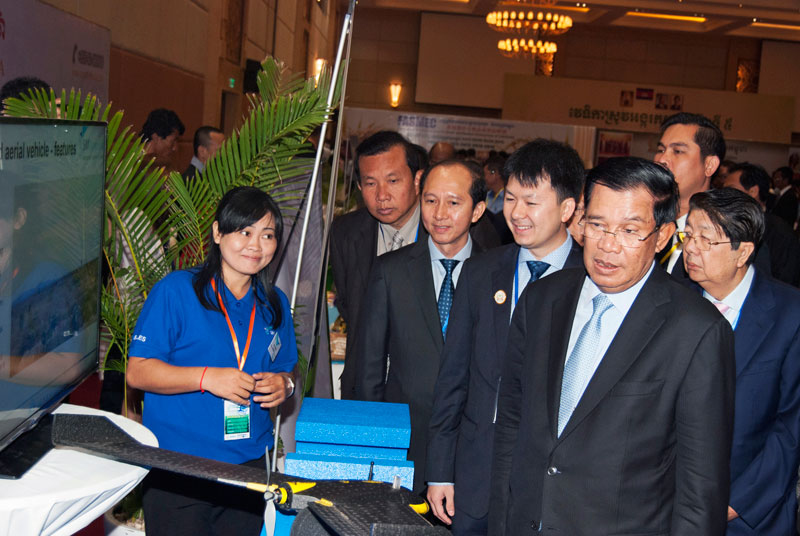

Launched in June as a joint venture between U.S. remote-sensing consultancy Waypoint Global Strategies and local conglomerate SOMA Group—run by Sok Puthyvuth, the son of Deputy Prime Minister Sok An and husband of Prime Minister Hun Sen’s youngest daughter—SMWaypoint aims to use drone-collected data to help reshape Cambodian industry.

“Whatever a human can do, if a drone can do it, it can do it quicker and cheaper,” said James “Jimmy” Jacks, a Texas native and SMWaypoint’s managing director.

Private companies have already hired SMWaypoint to inspect utility poles and count teak trees, while an environmental group has approached the company about studying Irrawaddy dolphins. The technology could be used in the future to settle land disputes, aid in disaster management and even hunt for gold, according to Mr. Jacks.

The exploding popularity of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) worldwide has spurred talk of a new “drone economy” that will bring $82 billion and 100,000 jobs to the U.S. alone, according to a recent report by the Association for Unmanned Vehicles Systems International.

But Cambodia’s first commercial drone consultancy faces several hurdles. Both regulators and business owners are unfamiliar with UAVs. Some drone experts believe the industry has oversold the promise of the devices. And even if it hasn’t, the services of SMWaypoint are currently out of reach for all but the largest landholders and businesses, limiting the company’s utility for subsistence farmers, small business owners and civil society groups.

In February last year, a camera-mounted drone operated by a German photographer buzzed the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh, startling Queen Mother Norodom Monineath and prompting City Hall to ban all unauthorized flights in the capital.

The Royal Palace incident, and subsequent detentions of filmmakers and tourists for similar infractions, highlight the novelty of UAVs in the civic sphere. That novelty is both a selling point and sticking point for SMWaypoint.

“There’s a strong demand for it, but people are apprehensive because the technology is very new,” said Verak Chhim, the company’s sales and marketing director.

For decades, UAVs were used mostly in war zones to gather intelligence, act as decoys and, later, drop bombs. Hobbyist-grade drones can now be bought for under $100, and the devices have increasingly been put to commercial use on farms, film sets and crime scenes, among many other applications.

The precision of UAV imaging makes drones particularly well-suited to collect data in agriculture. “You can see a leaf of a plant from 300 meters up,” Mr. Chhim said.

Veronica Justen, an assistant professor of crop science at the University of Wisconsin-River Falls, believes UAV imaging can unlock powerful insights for farmers.

“The aerial images can be used to assess many issues including crop stress (nutrients, water, pests), planting establishment problems and weed populations,” she wrote in an email.

When Mr. Puthyvuth heard about the technology, “He realized it was very close to his core business,” Mr. Jacks said.

As CEO of SOMA Group, Mr. Puthyvuth recognized the potential for drone use in the conglomerate’s extensive agricultural and timber holdings, Mr. Jacks said. And as president of the Cambodian Rice Federation—not to mention son of Mr. Sok An—he was well positioned to win over skeptics in business and government.

Mr. Jacks also boasts a colorful resume. In the early 1970s, he piloted food drops over Phnom Penh and fled the country with his Cambodian wife “just a few jumps ahead of Pol Pot.” He went on to serve as a pilot for former Congolese President Mobutu Sese Seko and the Saudi royal family, then managed the aircraft, yachts and other assets of a South American billionaire he declined to identify.

He returned to Cambodia in 2007 to act as a consultant for local airlines, becoming familiar with airspace regulations in the process.

Operating out of an office inside the SOMA Tower in Phnom Penh, SMWaypoint set about targeting Cambodia’s largest plantations, some of which cover tens of thousands of hectares and employ professional agronomists.

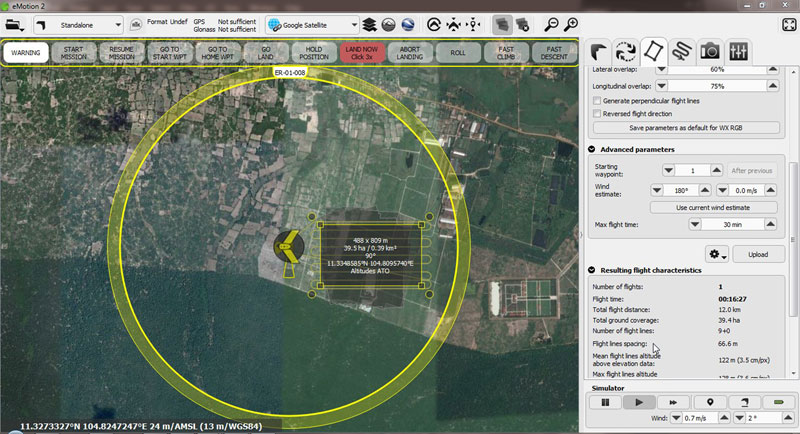

Those experts are already familiar with the data collected by SMWaypoint’s drones, which are launched by catapult and travel along a pre-programmed set of coordinates—the “waypoints” for which the company is named—to gather high-resolution photos of the land, thermal images and data to make 3D topographic maps and measure the stage of photosynthesis in crops.

The four UAVs in the company’s fleet retail for between $40,000 and $200,000. The “workhorse” of the operation, Mr. Jacks said, is an Insight Robotics drone with a 3.3-meter wingspan. The drone can survey some 1,800 hectares in two hours while cruising at 90 km per hour.

Farmers can use the data collected by UAVs to more precisely deploy pesticide, monitor the chlorophyll content of rice crops, or map the contours of a sugarcane plantation.

By comparison, humans are slow and unreliable data collectors, Mr. Jacks said.

“The way they do it now, they just send the humans out there looking up at the tree,” he said. “What if they tie up their hammock between two palm trees and take a nap? You’ll never know.”

There are similar promises of time-saving in the mining industry. UAVs mounted with magnetometers can survey a specific region, tipping geologists off to possible gold deposits.

But like all data collected by drones, these mappings are only useful when combined with other data sources and turned into actionable plans.

“You can’t just take it out and fly it,” Mr. Jacks said. “You might as well take a treasure hunter and go out and run him around.”

Indeed, some experts say the space-age promise of UAVs have been oversold by industry groups eager to draw attention away from ongoing privacy concerns.

In their paper “Agricultural UAVs in the U.S.: Potential, Policy, and Hype,” researchers Patricia Freeman and Robert Freeland write that media reports about agricultural drones often fail to consider the expense and expertise required to use the technology and predict a “period of disillusionment regarding the contributions of UAVs to agriculture.”

SMWaypoint charges between $4 to $8 per hectare for its services, depending on the type of data requested.

Mr. Jacks acknowledges that those prices put the services far out of reach for most of Cambodia’s subsistence farmers, who are still working the land “the way they did it a thousand years ago.”

The Texan said the company had been studying how it could partner with NGOs or local growers’ associations to provide their services at scale. “You obviously can’t work with them one on one—we’d go to the poorhouse.”

Yang Saing Koma, the former president of agriculture organization Cedac, said he hadn’t heard of SMWaypoint, but believed drone-driven data would be of little use to Cambodia’s rice farmers without support and education.

“I don’t think many farmers would make use of it,” he said. “Farmers prefer contact with people to get advice…on how they can grow better. This is the kind of information needed by farmers.

“They mainly rely on their tradition. But they need people to help them, to guide them. We need to send people to help farmers combine [UAV data] with other kinds of information.”

The Cambodian government is also rushing to catch up in regulating the devices. Mr. Jacks says his company is working closely with officials from the State Secretariat for Civil Aviation as they draft rules for UAVs.

However, it remains to be seen whether those regulations will provide rights groups with the same leeway for UAV use as powerful landholders receive.

Thun Saray, founder and president of rights group Adhoc, said he was not very familiar with UAVs, but believed they held both potential and potential threats.

“I don’t know how to balance between the privacy of Cambodian citizens, security of the country and uses for the public interest,” he said.

“It could be helpful if used in the right way—to know about the occupation of the land by the people, or the violation of the land by a big company,” he said. But those same companies “can use this kind of instruments to collect the ‘truth’ in the interests of the company.”

Mr. Puthyvuth hopes to allay some public concern surrounding drones by introducing them to students at the University of Puthisastra, which is also owned by SOMA Group.

“We already have letters of agreement with the university where we’ll use their facilities, we’ll send our instructions—not for a pilot course, but just to bring drones into the area of hobbies for students,” he said. “Those young guys, they’re so excited to be around it.”

If the enthusiasm catches on, Mr. Jacks thinks Cambodia is in a good position to profit from the technology.

“The whole world is just now getting on board,” Mr. Jacks said. “We’re really not that far behind.”