A surge in U.S. aid is helping Cambodia scale up work to rid its eastern provinces of the deadly detritus of old wars. With other countries pulling funding, deminers are leaving the west—where death and injury from old landmines and artillery shells are far more common—to do it. The consequences could be fatal.

Battambang province – Chhorn Souno knew his walk through the forest was a gamble.

His wife, born and raised in the area, had told him of the many battles the forest had seen between government troops and Khmer Rouge rebels making a last stand from jungle redoubts along the Thai border. His father-in-law, who lost a leg to a landmine while fighting for the rebels in the 1980s, had warned him too.

But Mr. Souno decided to take his chances.

Local villagers had been passing through the forest for years without trouble. He had done it himself a few times already. So when Mr. Souno stepped into the woods one day in November 2014, he figured the odds were on his side. It was almost midnight and he was well into a half-day’s walk home from the border, where he had spent the past week helping the army build a new outpost. Phin, with whom he had volunteered for the job, was a few paces ahead.

His next step changed everything.

As Mr. Souno’s weight bore down on the buried landmine, about the size of an ashtray, a spring-mounted firing pin just beneath the pressure plate was rammed into the detonator inside. The impact sparked a tiny fuse that ignited 50 grams of TNT packed in around it. The explosion knocked him to the ground.

“Pang!” he said, recalling the sound it had made. “When I stepped on the mine, I didn’t know what happened. I just heard ‘pang’ and I fell down.”

Recovered from the initial shock, Mr. Souno peered at his left leg. He saw a bloody foot torn to shreds but for the most part hanging on by bits of flesh and bone. Phin, uninjured by the blast, quickly tied a krama around the leg to stanch the bleeding and tried to carry him out of the forest on his back. But Mr. Souno was too heavy. After about a kilometer, Phin had to put him down and ran off to get help.

“When he left me,” he said, “that’s when I felt the pain.”

Before dawn, his wife and three police officers had returned with Phin and carried Mr. Souno to a hospital where doctors amputated the foot. A rehabilitation center in the provincial capital later fitted him with a prosthetic leg, free of charge. But the amputation and a 10-day hospital stay set him back $2,000, a fortune for a father of five with only a small cassava patch to his name.

When reporters visited him in April, Mr. Souno was stoic about what happened.

The business of feeding a young family leaves little time for mourning, yet his broad, friendly face looks older than its 33 years. With lean, muscled arms fashioned from a life of hard labor, he slipped off the prosthetic leg to show off the new foot he carved himself—a fist-sized block of wood with a few metal strips nailed to the bottom, better suited to the rough and tumble of rural life than the one it came with. When he’s not farming his cassava patch, he picks up whatever odd jobs he can.

Their home in Samlot district, off the grid on a hardscrabble hillside on the outskirts of a tiny town, is not a house so much as a bed—a few planks of wood about three feet off the ground and a clear plastic tarp for a low-slung roof. There are no doors. Family photos ring the three walls and piles of cheerful pillows and blankets fill in the rest. Perched on the floor of a narrow porch outside, Mr. Souno leaned over to massage what was left of his leg, which tapered evenly from the knee to a smooth round nub about halfway to where his foot would be.

“It’s really affected my family, but I still try to stand up and make money,” he said. “Before, I could do anything. Now I can’t carry heavy things, so I can’t do construction work like before.”

The hefty hospital bill has indefinitely delayed plans to move the family back to his home town a few districts over.

“I don’t want to stay here because it’s very hard and we make very little money,” he said. “I still want to return, but right now I can’t because I spent the money on my leg. I have spent everything on my leg.”

Mr. Souno is not alone. He is hardly even an exception.

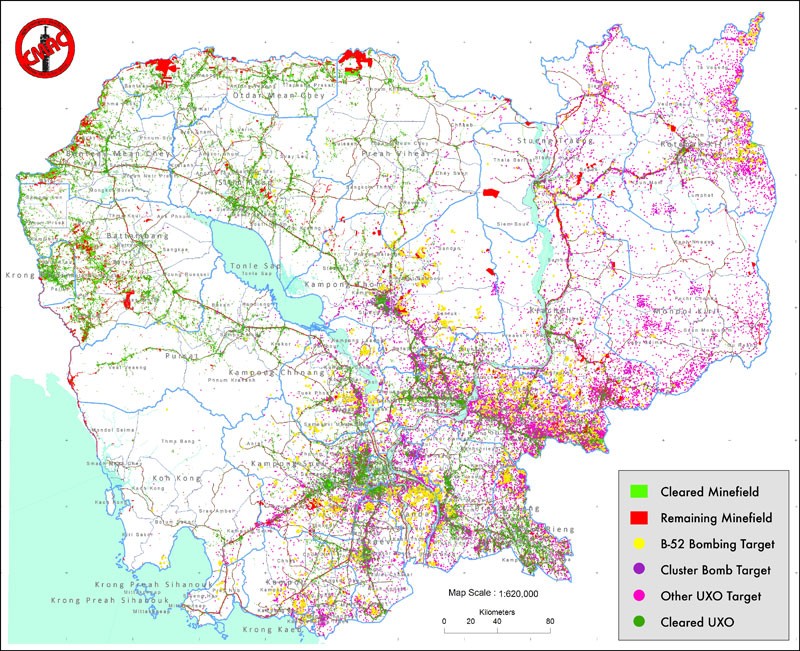

There is scarcely a corner of the country not scarred by old landmines and unexploded ordnance (UXO), mostly bombs, grenades and artillery shells. Since the fall of the Khmer Rouge in 1979, they have killed or injured more than 64,000 Cambodians, the brutal legacy of one of the most heavily bombed and landmined countries in the world. Battambang and neighboring provinces in the west have suffered the worst of it—by far—and still do.

But Cambodia is pulling deminers out of the west because the foreign governments funding much of the work are spending their new dollars elsewhere. Donors who have paid for demining in the west have pulled out of Cambodia to focus on other countries and other problems. The U.S., the biggest donor of them all, is at the same time boosting its spending in the east. The money scale is tilting and taking dozens of deminers with it. Moving them out of the west could cost lives and limbs, yet the government says it has no choice but to follow the money.

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]ince 1992, a year after the Paris Peace Agreements brought Cambodia back into the international fold, a patchwork of demining outfits have dug more than 1 million landmines and nearly 2.6 million pieces of UXO out of the ground. They have cleared almost 1,400 square km of earth. But still, only about half the job of cleaning up the minefields is done.

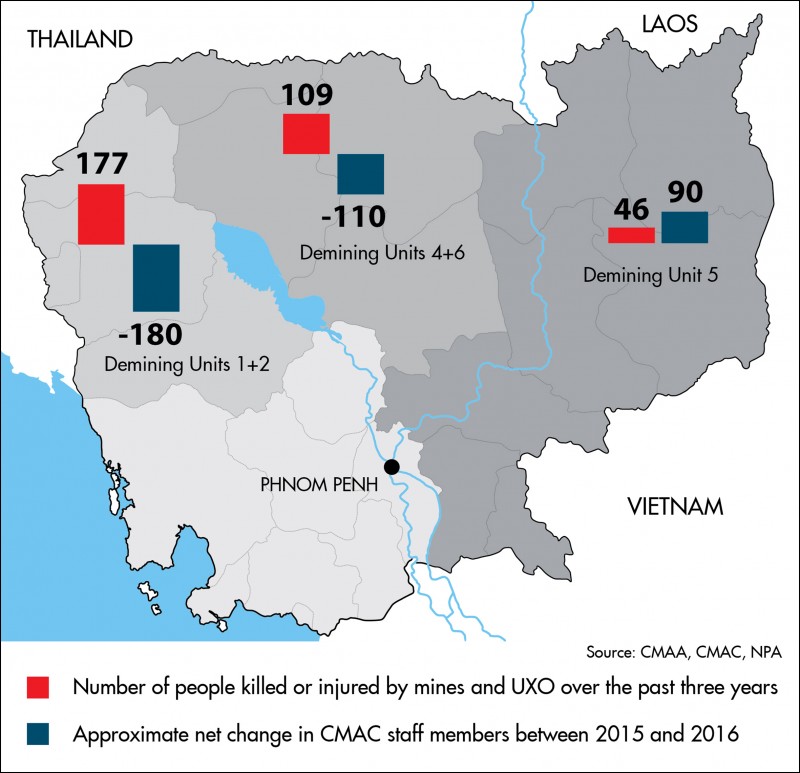

The Cambodian Mine Action Center (CMAC), the government’s demining arm, has done the bulk of the work, splitting the job between six units: Unit 1 and Unit 2 handle the west; Unit 4 recently absorbed Unit 6 after the latter lost its foreign sponsor and covers the central provinces in the north; Unit 5 covers the east. Unit 3 has moved around over the past few years but lately lost its own sponsor and ground to a halt.

The split makes sense, putting most of CMAC’s money and manpower into the northwest. It’s where most people are still being killed and maimed by old mines and UXO.

And yet CMAC recently pulled dozens of deminers out of the west to send them east—because that’s where it can afford to pay them.

The decision some donors have made to pull their demining dollars out of Cambodia has forced CMAC to make deep cuts to its staff and its operations in the west. Washington’s decision to move U.S. funding for CMAC east has made the cuts deeper.

Unit 1 and Unit 2 have had to cut their annual clearance targets this year by a combined 2,500 hectares—from 5,800 to 3,300—to cope with the loss of about 180 staff. The two unit chiefs said about half of their former employees have moved to Unit 5. The U.S. funds the unit through Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA). According to NPA, Unit 5 has gained about 90 staff this year to ramp up work across the eastern provinces, mostly in Kratie, Kompong Cham and Tbong Khmum.

The difference in casualty rates between the regions is stark.

Over the past three years, old mines and UXO killed or injured 376 people across Cambodia. Unit 1 and Unit 2, which cover four of the six deadliest provinces in the country (the other two are in the north), saw 177 of them—nearly half. The provinces Unit 5 covers saw 46. Kratie, Kompong Cham and Tbong Khmum, where Unit 5 is focusing its work, saw 24.

Deminers in the west said the heavy drawdown would likely cause accidents that could otherwise be avoided.

“Our demining will [be] delayed for another year, and maybe accidents will increase in our region because our resource has been reduced,” said Pring Panharith, the head of Unit 2. “If the people still need the land and cannot wait, I [think] the accidents will be more because our activity [is] less and the demand is quite big, so we cannot respond.”

Som Virak, the head of Unit 1, said they could compensate for some of the drawdown by working harder to educate locals about the dangers and how to avoid them. But it was a stopgap measure at best, he conceded, and no substitute for removing the danger itself.

“If we clear, we can reduce the risk 100 percent. But if we educate, maybe we can reduce the risk only temporarily,” he said.

The only sure bet is to clear the land, and CMAC is not working alone. It gets help from the military and a handful of smaller, private demining outfits. HALO and MAG, both headquartered in the U.K., are the biggest. HALO is increasing its own clearance targets this year by 327 hectares in the four provinces losing CMAC staff. MAG is increasing its clearance targets in Battambang and Pailin by another 50 hectares. But that won’t come close to the making up for the 2,500 hectares that won’t be cleared by CMAC because of the drawdown.

Gregory Crowther, MAG’s regional director for South and Southeast Asia, laid out a simple formula for predicting the consequences: fewer deminers plus time equals more casualties.

“The probability is that if you decrease mine clearance capacity in the west, over time the accident rate will rise as people…deliberately start to interact with contaminated land because they can see that nothing is happening, or less is happening.

“The reason that people don’t interact with items of UXO or with minefields is because they have confidence that somebody fairly soon is going to come and do something,” he said. “If that stops happening, people will develop their own coping strategies, but their own coping strategies are not as safe as the one of calling the police, or calling MAG, or calling whoever.”

“It’s not instantaneous,” he said, snapping his fingers. “But, over time, I would say yes, the trend would be: Lower capacity for clearance will lead to an increased accident rate.”

Besides its teams in Battambang and Pailin, MAG posts about a quarter of the deminers it has in Cambodia in Ratanakkiri province, which fills out the northeast corner of the country. Mr. Crowther, who has been demining the country since 2001, said he sees more pressure to open up new land in the west.

“And with increasing land pressure there’s increasing interaction with contaminated areas that were previously not required or needed,” he said. “There’s definitely more people in the west and more land pressure. As soon as we clear land, within six months it’s being used, and 85 percent of what we clear is being used for agriculture.”

“So there’s no question. And just instinctively, you go up to Pailin and you see the roads and you see the number of people. It was deserted 15 years ago; there was no one there. And it would take you six hours to get from Battambang to Pailin. Now you’re driving through it and there’s adverts for tractors.”

A paved road between the provincial capitals has cut the journey down to about an hour, and with new and better roads come more people.

But the road that worries some deminers most is the one that traces Cambodia’s border with Thailand. HALO, which works exclusively in the northwest, says the route is quickly changing from a narrow dirt track into a paved two-lane highway, drawing desperate farmers closer than ever to one of the most densely contaminated strips of land in the world—the K5 mine belt.

In the mid-1980s, in a bid to keep Khmer Rouge rebels and resistance forces holed up in Thailand at bay, the government conscripted hundreds of thousands of Cambodians for a massive building project dubbed K5 to fortify the border with earthen walls, spiked ditches, barbed wire and mines. In the end, more than two million landmines were laid along a 1,000-km stretch.

Parts of it have since been cleared. But occasional political and military flare-ups between Cambodia and Thailand over disputed borderland has kept long stretches off limits to deminers for years at a time.

Matthew Hovell, HALO’s regional representative and country director, said the border road’s metamorphosis makes a focus on demining the K5 belt more urgent than ever.

CMAC’s drawdown in the west, however, leaves fewer deminers in the area to do it.

“Whereas the community used to live maybe 10 km inland from the border…the community is now being drawn towards this new road, which brings it to within, on occasions, 50 meters of one of the world’s biggest minefields. So we will see a spike in mine casualties as people gravitate towards that,” Mr. Hovell said.

“It’s socio-economic pressure—landless poor. That’s where the last cheap land exists in Cambodia, because it’s mined, and people will try and cultivate that.”

For all the latent risk that’s still left across Cambodia, the ground beneath the country’s feet is safer than it has been in decades. Since 1996, when the number of people killed or injured by mines and UXO crested 4,000, annual casualty rates have tumbled steadily. The 111 cases reported in 2015 was the lowest yearly total since the Khmer Rouge was toppled.

But the work is not nearly over.

As a party to the U.N.-sponsored Mine Ban Treaty, Cambodia has already been granted one extension to the deadline it was given to clear away its anti-personnel mines, from 2010 to 2019. CMAC said there was “no way” Cambodia would meet the new target and will be asking for another extension as the date approached, this time to 2025.

Deminers still have hundreds of square kilometers left to clear in Battambang alone.

In Bavel district, about an hour’s drive out of Battambang City toward the Thai border, Dao Sunly’s 12-man CMAC team was a few weeks into a two-month mission to clear 11.5 hectares of overgrown field on the edge of Trapeang Kbalsva village.

The work is slow and painstaking. Progress is measured in meters.

Sweating beneath his visor and flak jacket, one of the men cut away a patch of low-lying shrub with a pair of shears and moved a length of rope—for keeping track of what they’ve already cleared—about a foot to the right. Another man stepped in to take his place, checked his metal detector to make sure it was working, and walked the length of the rope with the search coil a few inches off the ground before trading off with the man with the shears to start the cycle over again. Within sight, a pair of leashed and panting Malinois trained to sniff out explosives had their snouts in the dirt, double-checking a patch the team had already searched and cleared once.

“Mostly it’s anti-personnel mines,” said Mr. Sunly, an ex-soldier with a chiseled face and a piercing glare. He said the mines were of both Chinese and Russian make, a sure sign the field traded hands at least once between government and Khmer Rouge forces. Mr. Sunly, in his late 40s now, may have laid some of them himself as a young man. After turning 18 in Kompong Cham, he signed up for the army and was promptly transferred to Battambang to fight the rebels.

“I put mines everywhere,” he said. “When I was a soldier I put the mines in the ground to protect our base. I didn’t think about anything else. Now I want to take them all out and give the land back to the people.”

CMAC managers in Battambang said the drawdown won’t leave parts of the province like Bavel abandoned. With fewer deminers, they’ll just have to do less work wherever they go.

Mr. Sunly said he did not know about the deminers moving east. Neither did Dy Saroeun, the soft-spoken chief of Trapeang Kbalsva village, down the road from where the team was at work.

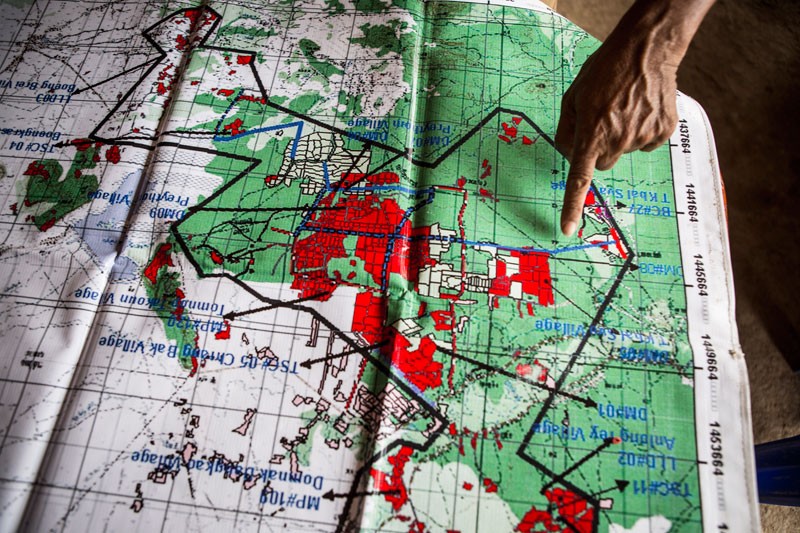

CMAC gave Mr. Saroeun a map of the area about two years ago. At home, over a dusty dinner table in the middle a spare dirt floor, he unfolded the large plastic sheet and traced a finger over his village and the contaminated land around it, filled out in patches of fire truck red.

“We don’t have a lot of farmland because we don’t dare to clear the forest, so the people are poor because they can’t farm,” he said. “Now they are better off because CMAC is clearing the land.”

Mr. Saroeun moved to the village in 1999 in search of cheap land himself. On the timber post holding up the middle of his roof, an old photograph of him and his wife had pride of place. On the walls, next to portraits of the royal family and a poster of the many mines and UXO locals might find in the area, were scenes of tropical beaches. Their aqua-green waters felt worlds away from the parched fields outside the village chief’s door, where a batch of cassava chips lay baking in the sun.

CMAC had been demining the area off and on since 2002, Mr. Saroeun said, but was far from finished. He hoped the western drawdown would not touch Trapeang Kbalsva.

“This area has a lot of mines and they are not finished,” the village chief said. “If they leave, people in the village will have more accidents. I have lived here for a long time and I know this area still has a lot of mines.”

He said landmines killed five people in the area in 2014 and destroyed two tractors last year. In February, a CMAC team drove a truck over an old road the locals thought was safe but ran over an anti-tank mine; the passengers escaped the blast unscathed but the truck was totalled.

“I think more people will get hurt by mines if CMAC reduced its work,” he said. “They should stay.”

CMAC says it would like to take Mr. Saroeun’s advice; it just can’t afford to.

The center’s director and unit chiefs say their hands are tied by the countries funding the bulk of their work. They don’t simply hand over a check and let Cambodia decide where to spend it. More often than not, they pick a part of the country and the money gets locked in.

For the past several years, much of CMAC’s work in the west has been paid for by a U.N. Development Program (UNDP) project called Clearing For Results (CFR). Foreign donors committed a combined $27 million to Phase 2, which wrapped up a few months ago after about five years.

Phase 3 has picked up where the second left off, but with a fraction of the budget and only one of the original donors—Australia, which has committed $7.7 million for another four years. Canada, Switzerland, the U.N., Austria, Norway, Ireland, Belgium and France have all pulled out of the project, though the UNDP is hopeful that Switzerland will come back and bump the budget for Phase 3 up to about $11 million.

The cuts have taken their toll on CMAC’s budget, dropping it from $14.1 million in 2015 to $6.8 million this year. CMAC expects a few more pledges to come through and raise that to $10 million or more by year’s end, but it says it will still have to shed a few hundred staff by attrition.

In the east, CMAC’s sole sponsor is the U.S. It’s where America has the most to atone for.

During the Second Indochina War, the U.S. bombed Cambodia to pieces, first going after North Vietnamese forces holed up in the east feeding fighters and firepower into South Vietnam down the Ho Chi Minh trail, later after Khmer Rouge guerillas closing in on the U.S.-backed government in Phnom Penh. What started out under U.S. President Lyndon Johnson with secret sorties close to the border grew into an unfettered carpet-bombing campaign under Richard Nixon that spread ever deeper into Cambodia like a bloody rash.

“[Nixon] wants a massive bombing campaign in Cambodia. He doesn’t want to hear anything,” National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger told a military assistant in December 1970, according to a government transcript of the phone call. “Anything that flies on anything that moves.”

By 1973, U.S. B-52s had made more than 230,000 bombing runs over Cambodia, pummeling over 113,000 sites. In 2006, on the back of newly released data from the Pentagon, researchers Ben Kiernan and Taylor Owen reported that some 2.7 million tons of ordnance were dropped on Cambodia—more than the total tonnage dropped by Allied forces during World War II—though they later revised the figure back down to “at least” 500,000. The Cambodian government says it has looked at the same data, checked it against what’s been found on the ground, and still believes the real tonnage is closer to 2.7 million, maybe more.

Estimates of how many Cambodians the strikes killed range from 5,000 to half a million. Most put the death toll in the tens of thousands. Some historians also blame the bombing campaign for Pol Pot’s rise—the perfect recruiting tool for turning ragtag rebels into an army with the numbers and the zeal to take Phnom Penh in 1975. The Khmer Rouge would go on to claim another 1.7 million lives, a quarter of the population.

But one of the tragedies of war is that the dying does not always end when the fighting stops. The bombs the U.S. dropped on Cambodia were supposed to explode on impact; many did not. Some of the 26 million sub-munitions scattered by the cluster bombs the U.S. used had failure rates as high as 26 percent during testing and likely failed more often in the field, and a failed bomb is still a deadly bomb.

The U.S. is striving for some redemption.

According to the U.S. State Department, the country spent $106 million on conventional weapons destruction in Cambodia between 1993 and 2014, more than in any other country in the region. Annual U.S. government reports show combined state and defense department spending in Cambodia on the rise recently, from $5 million in 2011 to $8.9 million in 2014, the last year for which the reports have figures. The U.S. Embassy in Phnom Penh said spending in 2015 and in 2016 were likely to stay level.

The money has gone to CMAC and private operators alike, and most of it to the west. But a growing share is going east, where the U.S. dropped the vast majority of its bombs.

CMAC Director Heng Ratana said the U.S. started funding Unit 3 in the early 2000s when it was stationed in the west, in Pailin, and followed it north to Preah Vihear before cutting support six or seven years ago. He said the U.S. started funding Unit 5 in the east at about the same time.

With most other foreign donors pumping money into the west, he said, “we [had] a long discussion and agreed that their funding…will look at [areas] heavy affected by U.S.-origin devices, UXO, so that means at the east.”

In 2014, the U.S. partnered with NPA, the Norwegian aid agency, for a project with Unit 5 called Clearance of Explosive Remnants of War in East Cambodia. Phase 1 ran from May of that year to September 2015 at a cost of $1.76 million. The U.S. bumped the budget up to $2.5 million for Phase 2, which will take it through to October. It’s that extra money and Washington’s decision to spend it in the east that has pulled some of CMAC’s deminers out of the west.

The U.S. Embassy declined a request for an interview. In a statement, it noted the State Department’s ongoing financial support for demining work in the west through HALO, MAG and Cambodia Self-Help Demining, another private operator.

“Due to the prevalence of U.S.-origin munitions and rising accidents in eastern Cambodia, the Department of State increased its assistance for survey and clearance in that region in 2014 by expanding assistance to the Cambodian Mine Action Center, which is administered through a grant to Norwegian People’s Aid. This increase brought Department of State assistance for survey and clearance activities in the east and the west to equal levels, approximately $2.5 million annually in both regions,” it said.

“In addition to U.S. Department of State support, the U.S. Department of Defense also provides humanitarian mine action first responder training to CMAC, RCAF [Royal Cambodian Armed Forces], and other counterparts to address legacy of war issues across Cambodia. Overall decisions about the regional allocation of clearance capacity are made by the Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority (CMAA), the government regulator for the sector. The U.S. recently agreed to fund a new server for CMAA to help the authority ensure that resource prioritization decisions are driven by data about accidents, socio-economic indicators, and other prioritization criteria.”

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]ut local servers don’t decide where foreign donors put their money. Mr. Ratana said spreading deminers around the country was a delicate balancing act, and not always performed on CMAC’s terms.

“While you have the limited resource, this business is about the tradeoff. You cannot have what you want,” he said.

“People may say, why not keep the deminers at the northwest while you keep it as [a] high priority? But, you know, sometimes financial resource allocation [is] also kind of [a] consideration and we have to compromise…. If you look at [Unit] 5, we [are] able to increase because the U.S. also provides the funding for this year with [an] increase to the east. So that [is a] good opportunity while the funding at the west pulls out, mainly from UNDP Clearing For Results.”

Mr. Ratana said his first choice would be to keep the deminers moving east in the west.

“It’s not a kind of satisfaction deployment,” he said. “If you give me a choice, I will choose the west.” He said he can’t make that choice “because the funding [is] in the east.”

Mr. Ratana described the deployment as a product of U.S. policy and part of what he called their “moral obligation.”

“If you give me a choice, I will give a choice to the west, no question. But they also have their own kind of policy guideline,” he said. “When you talk about the U.S., they have the guideline that they really want to target—like I mentioned, I repeat this word—U.S.-origin devices clearance. So we should understand that.”

In a perfect world, Mr. Ratana said, Cambodia and the foreign governments footing most of the bill to demine the country would work together to find a way to put their money exactly where it can do the most good.

“If the donor and the government have good coordination and [a] kind of compromise strategy together, that will be a great deal. But this never happens,” he said. “Sometimes they just try to fulfill their own mandate.”

Mr. Panharith, the Unit 2 chief, said conflicting mandates were pulling priorities dangerously out of sync.

“The U.S., they dropped a lot of bombs in Cambodia, so they want to help the areas [where they] dropped the bombs,” he said. “We need to clear everywhere [there are] high casualties, but the political [people], they have to think another way.”

Mr. Crowther, from MAG, agreed that Cambodia should not be adding deminers to the east at the expense of the west—ideally. But he said operators and the deployment decisions they make are, in the end, at their donors’ mercy.

“You can increase capacity wherever you want. We can increase it in the east and the west if we have the money. But we have to follow where the money is,” he said.

“In essence we don’t have any choice…. We have one main donor, which is the American government, and at the moment 70 percent of their funding is for the west and 30 percent is for the east, and that’s fine. But next time maybe they’ll reverse it. Would we choose to do that? Well, no. But if that’s what they want to do, there’s nothing we can do about it. If that’s what the American government decides they want to do, then that’s what we do.”

If CMAC wants to stop sending deminers east by pulling them out of the west with the money at hand, he said, it has one place to go.

“The only reason they’re having to do that is because the Americans are changing their balance of funding,” he said. “So the only person they should speak to is the American government, the American Embassy. But the American Embassy and the government of Cambodia don’t have the greatest relationship in the world.”

Jan Erik Stoa, NPA’s Cambodia program manager, has sat in on the government’s meetings with its demining donors and seen them talk past each other, meetings after which “donors keep on doing what they want to do.”

Even so, he believes NPA’s project with the U.S. and Unit 5 in the east was actually rebalancing CMAC’s deminers in the right direction.

“If you look at the balance between how many staff is working east of [the] Mekong River and how many staff is working in the western provinces, is that fair? That is 237 CMAC staff working in the eastern part of Cambodia covering all the provinces, and there is 1,500 working in the western part,” he said, and at least double that number adding in the private operators like HALO and MAG.

“So in my view you need to have a balance. Why? Because…more and more people are moving to the eastern provinces. And even if there is not that many accidents in the eastern provinces, there are accidents. The people are living in constant fear,” he said.

“The clearing of minefields and mines should have higher priority, of course. But there should also be some balance.”

Mr. Erik Stoa said the U.S. State Department was pleased with the progress NPA was making with Unit 5. He said funding for another year of work after October would either stay level or increase.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he new balance could be the new normal for Cambodia, decided in capitals across the Western world and out of Phnom Penh’s hands.

CMAC, MAG and NPA all spoke of a deliberate “shift” or “trend” in U.S. policy to see it do more to clean up its own mess here in Cambodia and across Indochina.

“There has been a shift in U.S. policy focusing on, ‘Let us clear up after our own, after munitions dropped by the U.S.’” Mr. Erik Stoa said.

In addition to its support for Unit 5, the U.S. has spent more than $1.1 million over the past few years turning 11 CMAC staff into the government’s first trained team of salvage divers to go after underwater UXO, much of it American. Some of the bombs the U.S. dropped on Cambodia fell on lakes and rivers. Golden West, which won the contract to train the divers, estimates that the Khmer Rouge also sank some 300 barges shipping U.S. supplies from South Vietnam in a failed bid to prop up the Lon Nol government in Phnom Penh, sending thousands of tons of munitions to watery graves.

The new dive team started exhuming those UXO last year.

As with Unit 5, the work is far from western Cambodia, mostly along the rivers that split the south of the country down the middle. And as dangerous as the work is—the divers often work in dark, muddy waters that cut visibility to almost nothing—neither the government nor Golden West know of a single death or injury underwater UXO have caused in recent years. CMAC said it asked the U.S. to fund the team in part to clear the way for future bridge and port projects, yet the center managed to clear out the bottom of the Mekong at Neak Loeung for a $127-million bridge that opened last year with divers it already had—well before the new team went operational.

At the same time that the U.S. is scaling up in the east, hope is fading that the donors scaling down in the west will be coming back. There is also a growing fear that others will join them.

Napoleon Navarro, head of policy for the UNDP in Cambodia, said some of the country’s traditional demining donors were pulling support for a few reasons. He said landmines were less of a global problem now than they were 20 years ago and that new priorities were competing for shrinking aid budgets. He cited the refugee crisis in Europe as a prime example.

But even the money donors are still spending on demining is moving to countries verging on collapse, going through war or just out of it—“fragile states” in the argot of foreign affairs.

Mr. Hovell said HALO lost Finland’s support after its government cut its global humanitarian aid budget in half about a year ago.

“That caused them to evaluate and reappraise where their money was best spent. They feel their less resources are better spent in fragile states, immediate post-conflict countries,” he said.

Mr. Crowther said other donors have been doing much the same.

“So you’re finding that donors are increasingly putting their mine clearance money, their mine action money in areas that align with their broader funding strategy, which is to support fragile states and not developmental activities,” he said. “Partly that is because there’s a belief that once a country gets to the point where it’s developmental activities, like it is in Cambodia, that the government should have developed, or should be able to deal with the problem of minefields or cluster munitions contamination itself, which is to a certain extent true. The question is, at what point does that happen?”

Cambodia remains one of the poorest countries in Southeast Asia. But after a decade of 7-percent-plus growth in gross domestic product that’s delivered it to the brink of low-middle income status, expectations are rising that the government wean itself off of aid—for demining and everything else.

The message may not be getting through. Of CMAC’s $14.1 million budgeted in 2015, the Cambodian government paid for $475,000, according to CMAC, about three times less than what it paid the year before.

Mr. Navarro said grants will give way to more and more loans, which tend to pay for less demining, and that the trend “will likely persist over the medium to long-term.”

But there is hope.

Mr. Crowther said Cambodia could probably hold on to more of the demining dollars still out there for longer if it were to come up with—and stick to—a timetable for gradually raising its own contribution.

That way, he said, “donors would be able to say, ‘OK, I can understand that and we will allocate three years of decreasing funding to HALO and MAG whilst you develop your national capacity and provide more and more money from your central government’s budget.’ But there is no kind of plan like that.”

Some of Cambodia’s biggest demining donors are still here, including the U.S., the U.K., Australia and Japan. But there are no guarantees they will stay, Mr. Crowther said. The U.K., for one, is set to whittle down the list of countries it supports with demining aid at the end of 2017.

“The bigger problem is that they might not keep [Cambodia] on the list, the same as the Finnish government, the same as the German government, and the same as the Belgian government,” he said. “The same as Canada. So suddenly it’s a whole range of middle- to large-scale donors that are no longer funding anyone. That’s the bigger concern.”

“Things like this can become a self-fulfilling prophecy,” Mr. Hovell said. “If everyone’s saying…donors are walking away, donors will walk away. If we carefully articulate the problem, come up with a good strategy, engage donors, there’s all to play for.”

He said drawing attention to the growing risks Cambodians are facing as they move ever closer to the K5 mine belt could play a part in keeping donors committed to the country.

“I think it’s a factor,” he said. “Has the situation changed? Yes. We’ve got a lot more people that are gravitating toward a massive minefield.”

A new strategy plan being prepared for CMAC for 2017-2019 could help fill in some of the gaps being left by donors in the west. Mr. Ratana said it will likely call for putting more of CMAC’s resources along the Thai border and for the government to cover a larger share of the costs.

But strategy plans, like computer servers, don’t pay the bills. The government had aimed to be paying for 20 percent of the work of its own deminers by 2015. The $475,000 the government allocated to CMAC last year covered 3.4 percent of its budget that year.

The UNDP hopes to nudge the government into upping its stake by convincing it to built the costs of demining into public investment projects, from agriculture to transportation. It already happens on occasion; Mr. Navarro would like to see the government make it policy. But he admitted that the approach would not necessarily put the focus on the most dangerous parts of the country.

“Our studies show that if you want to help the people, you really have to go to the forest,” he said. “And that’s where the casualties seem to be at this point. That’s what the studies show.”

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]r. Souno said the forest where he stepped on the landmine in 2014 had still not been cleared. The initial fear neighbors had that the area was still contaminated soon wore away against the hard reality of making a living.

“After I was injured, they stopped walking through the forest for a while. Now they go through there again,” he said. “The people here depend on the forest. They go into the forest to hunt. Sometimes someone hires them to cut down some trees.”

Government maps show Samlot district still pockmarked with minefields. In early April, local CMAC staff said there had been two accidents in the district in the past few days: a man who died after driving his tractor over an anti-tank mine, and another who survived a smaller mine blast while farming on foot.

Mr. Souno said government deminers were also finding mines along a 52 km stretch of dirt road running through Samlot that’s being widened and upgraded.

The road takes travelers part of the way from Battambang City to Mr. Souno’s village and buzzes with new life. Three different wedding parties were gearing up on a short stretch one afternoon, their dolled-up guests arriving in loud scarlet and lavender dress. Pepper farms ran up and down the hills as trucks brimming with cassava plied the dusty road. Metfone and Cellcard fought it out for new mobile customers from banners hanging off of homes and shop houses. At almost every corner was an ad with a shiny new tractor.

As the night fell down around Mr. Souno’s home on the quiet hillside, locals huddled beneath the thatched awning of a neighbor’s house and a naked fluorescent bulb running off battery power to watch the evening’s soap on a small, battered TV set. A harsh white light spilled out into the darkness.

Mr. Souno reflected on the deminers leaving the province.

“I think more people will have accidents if they move the deminers to other places because CMAC has not finished finding the mines here,” he said.

“I am sad the deminers are leaving because even with the deminers who were here people still had accidents. If they leave, how will it affect the village? Most people depend on the forest. If they don’t go into the forest they can’t support their families. But if they keep going into the forest, they will have accidents,” he said.

“People are going to die.”