For Nuon Chea, the greatest threat to the Khmer Rouge lay within its own ranks.

“If we did not kill the internal traitors in our party, if we did not smash the enemy, there would be no Cambodia today,” the regime’s “Brother Number Two” tells journalist Thet Sambath in the book “Behind the Killing Fields.”

“If we looked at the resistance movement when we fought an enemy that had good weapons and artillery, we thought it was a big deal. But the internal enemies were the worst and even more dangerous to the party and the country,” he says.

Far from being unified, Nuon Chea—who is on trial at the Khmer Rouge tribunal for crimes including genocide—argues that the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) was wrought with internal strife as powerful factions plotted to overthrow the regime’s leadership.

This theory of internal conflict has been the bedrock of Nuon Chea’s defense at the court since the start of his previous trial for crimes against humanity in 2011. Contrary to widely accepted characterization of the CPK as a highly centralized party controlled by Pol Pot and his most trusted advisers, Nuon Chea’s lawyers argue that many of the atrocities attributed to the regime’s leadership were actually carried out by rival factions without any authorization.

“Rather than being ‘strictly hierarchical’ and ‘pyramidal,’ the CPK was cleaved with deep factional divisions and plagued by internecine armed conflict,” according to a document released as part of Nuon Chea’s appeal against his guilty verdict in June last year.

“‘Zone leaders’ such as Sao Phim and Ruos Nhim, rather than being subordinated to Pol Pot and Nuon Chea, were powerful leaders who exercised substantial independent authority with which Pol Pot, Nuon Chea and others could not lightly interfere,” it reads.

“Sao Phim, Ruos Nhim and others such as Koy Thuon leveraged their authority from the earliest days after the liberation on 17 April 1975 to foment rebellion and/or treason against the legitimate government of Democratic Kampuchea.”

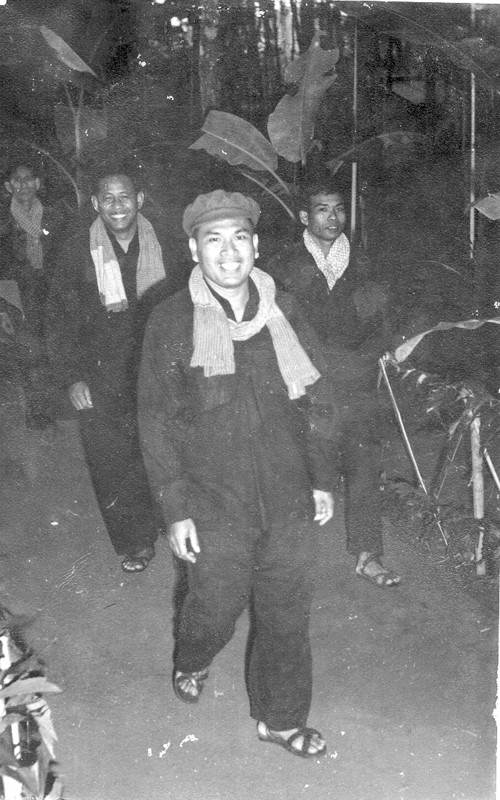

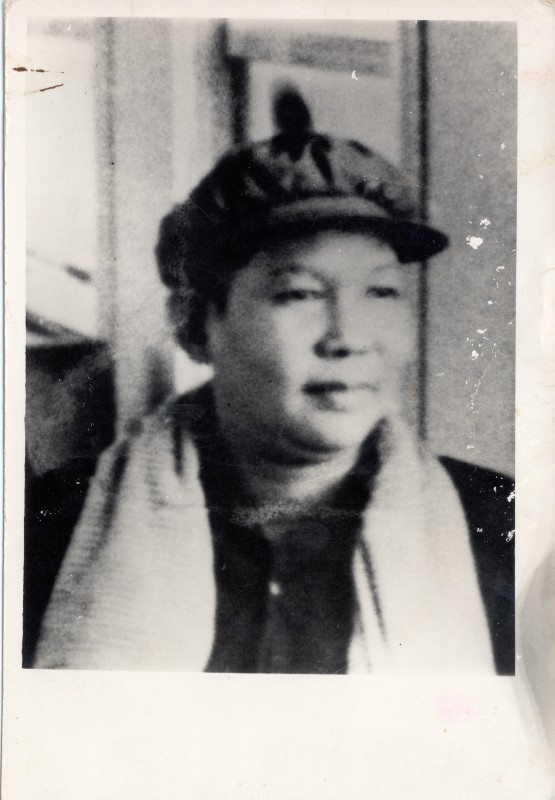

Ruos Nhim was a carpenter who joined the anti-colonial Issarak movement before eventually siding with the Khmer Rouge. In “Behind the Killing Fields,” Nuon Chea claims that Ruos Nhim was arrested and sent to the Phnom Penh’s notorious S-21 security center after being accused of plotting with Sao Phim to overthrow the party leadership and of providing insufficient food to the people living in his zone—claims Ruos Nhim “confessed” to under torture at the prison.

According to a transcript of his confession in the book, Ruos Nhim and Sao Phim arranged a meeting in June 1977 during which they hatched a plan to overthrow the government with the help of the Vietnamese.

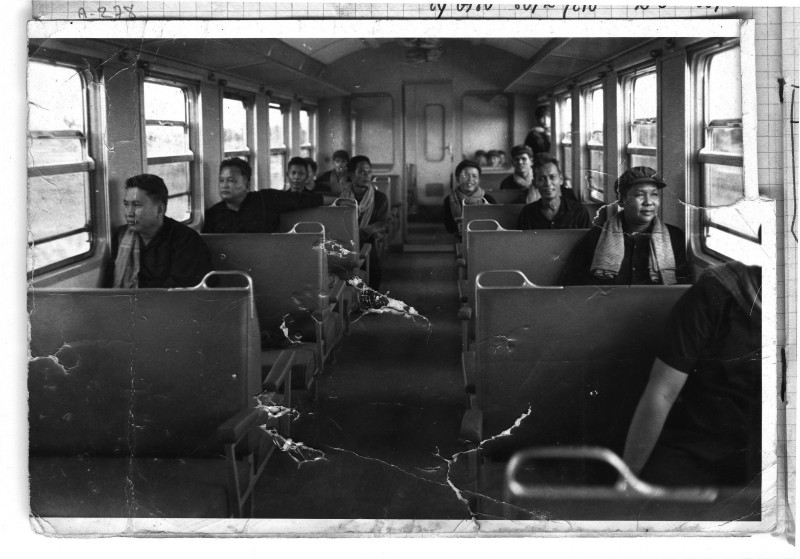

Nuon Chea claims that Sao Phim—a former farmer and soldier who decided to take up arms against the French in the 1950s—was like a brother to him after they met during the early days of the Cambodian communist movement of that decade. As the movement gained momentum in the ’60s, Sao Phim acted as Nuon Chea’s bodyguard, before being put in charge of the vital East Zone, which shared a border with Vietnam.

But when purges of suspected traitors within the party began to be carried out with increasing frequency, the East Zone became a primary target due to fears that the region’s leaders were colluding with the Vietnamese, and Sao Phim committed suicide in 1978 after escaping an attack by forces loyal to the CPK’s central leadership.

Others “smashed” by the regime over accusations of treachery and attempting to overthrow the party include Deputy Prime Minister Vorn Vet, North Zone Secretary Koy Thuon and West Zone Secretary Chou Chet.

An article penned by Anthony Paul and published in Asiaweek magazine on January 26, 1979—just weeks after Vietnam’s overthrow of the Khmer Rouge—seems to support the theory that the communist regime was rife with warring factions as early as 1977.

“Commune workers were aware that armed resistance to the Pol Pot authorities had existed in Cambodia for a long time,” Mr. Paul wrote.

“Since July 1977, fighting had been going on in dense jungle around the Tonle Sap. In that month, villagers had heard the sounds of heavy artillery and automatic weapons; almost every week thereafter, they heard them again. Khmer Rouge soldiers told them of fighting between Pol Pot forces and guerrilla units led by a certain Ruos Nhim, said to have been the former Khmer Rouge commander of the northwest military region,” he wrote.

“Accused by Pol Pot loyalists of being pro-Vietnamese and an agent for both the CIA and the KGB, he had fled to lakeside guerilla redoubts, along with a deputy commander named San, a divisional commander, Neou, [and] a substantial force and quantities of arms and ammunition.”

The article also mentions villagers who were concerned that family members had been caught up in the “Ruos Nhim fighting” after they failed to return from a trip to collect fish paste near the Tonle Sap lake.

Rob Lemkin, a British filmmaker who with Mr. Sambath co-directed the documentary “Enemies of the People”—which includes in-depth interviews with Nuon Chea—said the CPK was far from unified, and that he had evidence, in the form of unseen interviews, of planned rebellions less than a month after the communists took over Cambodia.

“Within a month of the takeover of power by the Khmer Rouge—Pol Pot, Nuon Chea and so on—senior leadership in the CPK were making separate plans for a separate military-backed administration and they were trying to work out how to achieve that,” Mr. Lemkin said last week from his home in the U.K.

“This was really a kind of civil war that was going on inside of Cambodia, but it was a secret civil war because of the nature of the totalitarian state that they had created which had shut its borders to the rest of the world so the rest of the world couldn’t know exactly what was going on.”

Although he declined to say more about the interviews that support this theory—as he plans to include them in upcoming projects—Mr. Lemkin said they were “sort of consistent with the fragmented evidence that you get from Tuol Sleng.”

“Of course, with all torture confessions, often people do say things, and the interrogators write all kinds of things down which are kind of just to please their immediate superior,” he added. “But if you look at the analysis of what those confessions talk about, they do show you really quite a lot of actual real organizing by people who are not really keen for the Pol Pot leadership to remain in control of the country.”

Mr. Lemkin insists he has no interest in absolving Nuon Chea or Khmer Rouge head of state Khieu Samphan of the crimes they are accused of—he says there is “no question” that the Khmer Rouge committed genocide against ethnic Vietnamese—but believes that the likes of Ruos Nhim had considerable autonomy over their regions.

He notes that the 1975 massacre of former Khmer Republic soldiers at Tuol Po Chrey has been attributed to Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan by the tribunal, despite the fact neither were mentioned once in three pages of legal findings related to the site attached to their guilty verdict in August 2014. (Both were convicted of crimes against humanity.)

“Ruos Nhim ordered it. That was the evidence that the court had,” Mr. Lemkin said. “There is evidence that it was decided by the regional Khmer Rouge hierarchy, which had fought an extremely brutal civil war against the Lon Nol people in Battambang and Pursat areas.”

Before he died while on trial alongside Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan in 2013, “Brother Number Three” Ieng Sary, the regime’s foreign minister, claimed that Sao Phim instilled fear in Khmer Rouge leaders including Pol Pot.

“Even Pol Pot and Nuon Chea, when they were in Sao Phim’s Zone, the East Zone, they were afraid of Ta Phim,” he told academic Stephen Heder, using a nickname for the regional commander.

“I went with them once, and I knew that and saw that. That is, Pol Pot himself did not dare go down below: He was afraid of Ta Phim,” he said. “So, in that zone, if Sao Phim wanted to kill and wanted to do something, it was not necessary for him to ask [the] upper echelons. The organization was like that; each zone was independent, almost what would be called kill as you please, do as you please.”

Dany Long, an investigator for the Documentation Center of Cambodia who estimates that he has interviewed about 4,000 former Khmer Rouge cadre, said he had encountered some evidence of plans by disgruntled soldiers to rise up against the center, but nothing more substantial—until the later Vietnamese-backed rebellion that overthrew the regime.

“When I interview with the cadre in Kompong Cham and Kompong Thom, some cadre said they did not like Pol Pot’s leadership style because they evacuated people and they made people live in the cooperatives, and they said they wanted to fight with Pol Pot,” Mr. Long said.

“They said that they prepared weapons…. Some groups wanted to make a coup d’etat. They said in their unit there was some plans to prepare weapons, to prepare soldiers [but] they just waited for some orders from the top leaders,” he said. “Those orders never came.”

Mr. Long believes Ruos Nhim and Sao Phim had a more progressive vision for Democratic Kampuchea—one that included money and markets—but only started planning rebellions in 1978.

“They still worked with Pol Pot as normal until in early 1977, when the central committee started to arrest some cadre in those zones and Sao Phim and Ruos Nhim also cooperated with Pol Pot to arrest the cadre themselves,” he said. “Then they started to suspect and wanted to fight against Pol Pot in 1978. They started to know Pol Pot wanted to purge all cadre in their zones.”

Craig Etcheson, a prominent researcher who served as chief of investigations in the Office of the Co-Prosecutors at the Khmer Rouge tribunal for six years, dismissed the theories of CPK infighting.

“I do not believe there was any inherent factional conflict within the Party. It was a disciplined and united Party, and the senior cadres were all loyal to the Party Center,” he said in an email.

Mr. Etcheson acknowledged that plots to overthrow the CPK center were mentioned in confessions obtained at S-21, but said the circumstances under which the confessions were obtained—torture—negated their probative value.

“In assessing the validity of that material, however, one needs to take into account the fact that, especially for ranking cadres who were sent to S-21, the only way to end the torture was to deliver a convincing description of a plot against the Party Center, along with long lists of your co-perpetrators,” he said.

“But when you cross-check all the plots described in the many confessions against one another, it really just doesn’t add up. It was only through a supreme act of imagination by Duch that they could assemble a coherent master plot against the Party,” he said, using the revolutionary alias of S-21 prison chief Kaing Guek Eav, who in 2010 became the first Khmer Rouge official to be found guilty of crimes against humanity.

Addressing claims that Ruos Nhim and Sao Phim planned to overthrow the party center, Mr. Etcheson said evidence actually pointed to the contrary.

“If you look in detail at how both Sao Phim and Ruos Nhim reacted to the purges of their own zones, it gives the total lie to Nuon Chea’s delusions about what really was going on,” he said.

“In both the purge of the Northwest Zone and the purge of the East Zone, whenever the Party Center said this person needs to report to us in Phnom Penh, that person was loyally sent almost every single time—the rare exceptions being people like Hun Sen, who decided he would run in the other direction,” he said.

“In this fashion, both Sao Phim and Ruos Nhim were totally complicit in almost completely gutting their own zone staffs, before they finally realized what was going on.”

The way the two commanders met their end also points to their loyalty, Mr. Etcheson said.

“When the S-21 ‘catchers’ finally showed up at Nhim’s house, there was no one left to protect him—he had already sent them all to S-21 on orders from the Center. Does that sound to you like what the author of a factional rebellion would do?” he said.

“The same thing happened in the East. When the Center’s forces finally attacked at the end of [mid-1978], Phim said, oh my god, [Defense Minister] Son Sen is a traitor! I have to get to Brother Number One and tell him!” he added.

“And as he was attempting to cross the Mekong to Phnom Penh to warn Pol Pot of Son Sen’s treachery, he was pounced upon by Center forces, barely escaping with serious wounds, and suiciding shortly thereafter as he finally realized that he had been betrayed by his own leader.”