Ouch Theara performs with Doch Chkae. (Steve Porte)

Ouch Theara performs with Doch Chkae. (Steve Porte)For a group of friends who spent endless days and nights scavenging in Phnom Penh’s notorious Stung Meanchey dumpsite as children, U.S. rap-metal pioneers Rage Against The Machine would seem an unlikely source of inspiration.

The world of Ouch Theara, his brother and his friends extended no further than the daily ritual of picking through the discarded detritus of other people’s lives.

“I had no parents, so when I was young I lived with my grandmother and other relatives. I had to pick up the trash to recycle every day to…support my grandmother,” Mr. Theara, now 19, said in a Phnom Penh cafe this week.

“I never had the proper time to go to school because I was so busy with picking up the recycling to survive.”

There seemed little hope of any future beyond the dump.

Then, after years trawling through the sprawling scrapheap, his grandmother passed away. With no family members left who could afford to look after him, Mr. Theara, then aged 12, and his brother were placed in the care of an NGO, Moms Against Poverty, with other orphans. It would prove to be a turning point in both their lives.

It was here that Mr. Theara was introduced to the world of heavy rock by Swiss-German musician Timon Seibel, who had just joined the country’s only metal label Yab Moung Records in 2014, and would visit the NGO to share his passion for the music.

“Before I just listened to music, but then Timon came and he played guitar,” Mr. Theara said. “Then he showed me bands from the U.S. like Rage Against The Machine. I liked it and then I just told him that I wanted to play guitar, drums or sing.”

“I kept going…and then I knew Slipknot. I liked them and I decided I wanted to be the same as Slipknot.”

There was something about the uncompromising aggression and rebelliousness in the music that Mr. Theara identified with.

He soon started seeking out metal himself. When Mr. Seibel took him to see Sliten6ix, a pioneer of Cambodian metal, playing at Phnom Penh’s Show Box bar in 2014, he decided to set up a band of his own the following year.

His brother, Ouch Hing, became the drummer; long-time best friend Sok Vichey took on guitar; the bassist, Sochetra Pic, was also living under the NGO’s care. All the band’s members had come from the Stung Meanchey dump and grown up together, creating a bond that runs deep.

Mr. Theara decided on the group’s name Doch Chkae, which translates to “like a dog.” A widely pejorative term in Khmer, he said it was used to portray how he felt society perceived him as an orphan from a dumpsite.

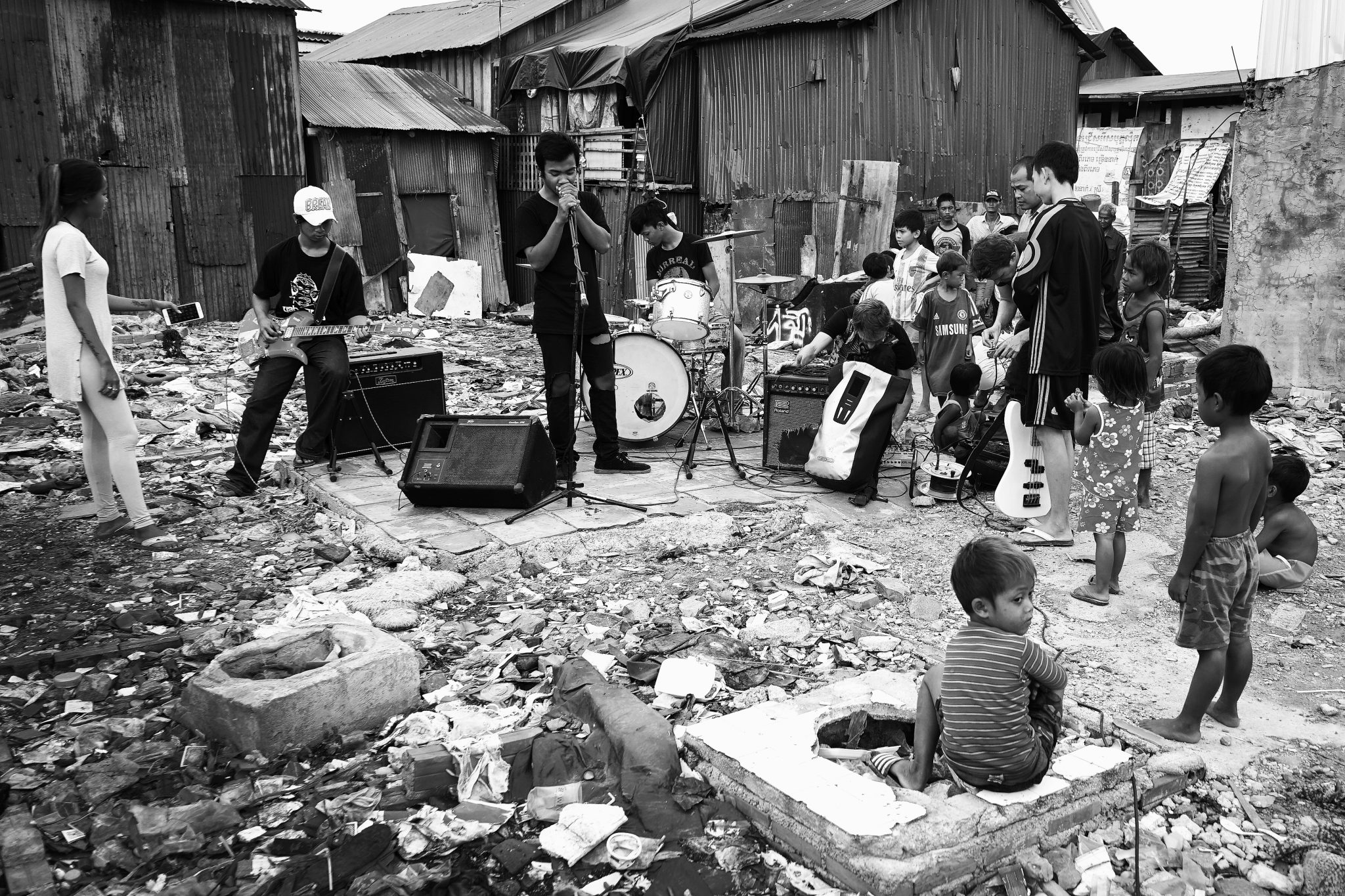

Doch Chkae perform in their former neighborhood at the Stung Meanchey dumpsite. (Yab Moung Records)

“We chose this name because our lives are like dogs. For a dog, at least they have owners, but for us, we don’t have parents to take care of us, we only have siblings. Therefore, we named ourselves ‘Like Dog,’” he said.

The band released two singles online through label Yab Moung last year, including “Kham Knea Doch Chkae,” or “Bite Each Other Like Dogs,” which was accompanied with a video of the band wearing collars and leashes and screaming from the confines of cages to imitate the canines they identify with. Theara’s snarling vocals are matched by the intensity of the drums and guitars. It has since racked up tens of thousands of views online.

Lyrics to another song, “Chkout Doch Chkae,” or “Crazy Like a Dog,” include the lines “I am crazy like a dog, like a dog is rabies crazy. I really hate my f—ing life, so really f—ing hateful much. I like to be a f—ing crazy dog, because then you’re starving poor without anything.”

Mr. Theara finds the whole process cathartic, the frenetic music giving him an outlet to let off steam, a release for the anger and frustration inside. When he’s not making his own music, he can be found at his job, teaching kids at Moms Against Poverty to play drums.

The band members write music collaboratively and have played live around Phnom Penh, including at last month’s Golden Street Festival on Street 278.

Despite the growing popularity of the band, Mr. Theara admits that many perceive his death metal music—the anthesis of the cheesy bubble-gum pop beloved by many young Cambodians—in a derogatory way.

“When we play the music…it’s common that people say ‘like dog, like dog’ both older and younger people,” he said. “They say it’s just noise. They say, ‘What are these stupid songs you are singing? It is not listenable.’”

Not that 17-year-old guitarist Vichey is fazed.

“They cannot understand the words that we sing. It’s just screams and nobody understands,” he said. “Who cares? I don’t care.”

“I just want to get better and better so a Khmer metal band can be famous.”

Doch Chkae’s emergence has coincided with something of a comeback for Khmer metal in Phnom Penh.

A budding scene emerged around 2012 with a few bands and growing crowds, but it disappeared back into the darkness in 2014 after numerous groups, including Sliten6ix, went their separate ways. Last year, however, the pioneers of Khmer metal made their ferocious return.

Speaking in the Phnom Penh bar-cum-tattoo parlor where he works when he’s not on stage, Sliten6ix lead vocalist Vanntin Hoeurn, 24, explained how he discovered his love for metal while learning English as a teenager.

“I started off just listening to English music in general because I was learning English and then I saw some alternative rock bands and I was like, ‘this is heavy,’” said Mr. Hoeurn, better known around town as Tin, who speaks with a broad British Mancunian brogue—picked up from the friends he learned English from—despite living in Cambodia his whole life.

It was soon after discovering his love for metal that Mr. Hoeurn started Sliten6ix in 2011.

“At the time I didn’t know I could sing so I was just like, ‘F— it. If I can’t sing I’m just gonna scream.’ That’s why I was like, ‘Let’s go really heavy,’” he said.

Although it’s debatable whether Sliten6ix was the country’s first metal band, there was no real precedent for what they were doing when they started. The band quickly built up a following in certain circles, while their music was met with confusion in others.

Sliten6ix perform at a Phnom Penh street party earlier this month. (Steve Porte)

“The family were just bemused. They don’t know what it is, but were like, ‘You do what you do. You still go to school; that’s good enough for us,’” he said.

“I think our first two gigs we did at one of my friend’s houses,” he said. “We got a lot of confused neighbors popping their heads around. We didn’t really care. We just did it.”

It didn’t take long for Sliten6ix to begin making waves in Phnom Penh, with bigger crowds attending their chaotic shows, column inches being devoted to their rise and the feeling of a real scene beginning to form.

“It was such a tight-knit group back then. Some people didn’t know what the f— they’d got themselves into,” Tin said, laughing.

But as things were on the up, in true rock ‘n’ roll style, it all fell apart in 2014.

“The band was so jaded,” he said. “We just got sick of each other.”

During a couple of years apart, in which Mr. Hoeurn embarked on his Tom Waits-esque growling blues project Phnom Skor, he never turned his back on his heavier roots and his disdain for the “commercialized, plagiarized music” popular on the Cambodian airwaves.

“Metal has been a big part of my life since I was young. There was always a tingling idea at the back of my head that maybe I could do it again, but couldn’t really see people that could see eye-to-eye,” he said.

Last year, a call came from the band’s drummer Alan Ou, who wanted to give Sliten6ix another shot. With a new guitarist, Nara Tsitra, on board—who Tin says “forced everyone to not be lazy f—wits”—the band was reborn.

Sliten6ix swiftly penned and recorded their first EP “Hiraeth,” which was released in December, and this month embarked on their first foreign shows in Ho Chi Minh City, where heavy metal is more enthusiastically embraced.

Although the band’s sound has evolved since the early days, he said, Sliten6ix has maintained its nihilistic ethos that has rekindled the spirit of six years ago.

“Since we got ourselves off to Saigon, I think the boys got a bit of a taste for the touring, seeing all these different people and seeing that scene doesn’t just exist here, it’s all around the world. I think touring is very good to maintain that spirit,” he said.

Rejuvenated and back on the road, Mr. Hoeurn is optimistic—albeit realistic—about how far Sliten6ix and Khmer metal can go.

“Of course, I would love to see [major success], but right now I just want to tell other people, ‘OK, we don’t get famous, maybe the scene is not going to go [big], but who cares?’” he said, dragging on the last of a cigarette.

“If you like doing it, just keep on doing it.”

Doch Chkae frontman Mr. Theara is dreaming big, however. He hopes to follow in the footsteps of his heroes.

“I want my band to be famous in Cambodia, for people to know us and to let them follow us. Our country doesn’t have aggressive music like this.”

(Additional reporting by Buth Kimsay)