Dirty Business

As lakes are filled around Phnom Penh, sewage and flooding problems worsen. It’s a familiar story and Boeng Tompun presents the next chapter.

By Brendan O’Byrne and Sek Odom

July 14 2017

A politically connected conglomerate begins to fill in a lake in Phnom Penh. Poor residents lacking land titles are forced out. The city’s sewage and drainage problems worsen, while international donors’ plans to remedy the situation are stymied.

It’s a scenario recognizable to anyone who followed the Boeng Kak land dispute, in which thousands of high-profile evictions followed the 2008 decision by real-estate developer Shukaku to fill the northern lake with sand. City Hall’s sale of Boeng Kak to the company headed by CPP Senator Lao Meng Khin led to a prolonged protest movement and caused the World Bank to suspend its funding to Cambodia in 2011 for five years.

Now history may be repeating itself, with the city’s southern Boeng Tompun lake in a developer’s sights.

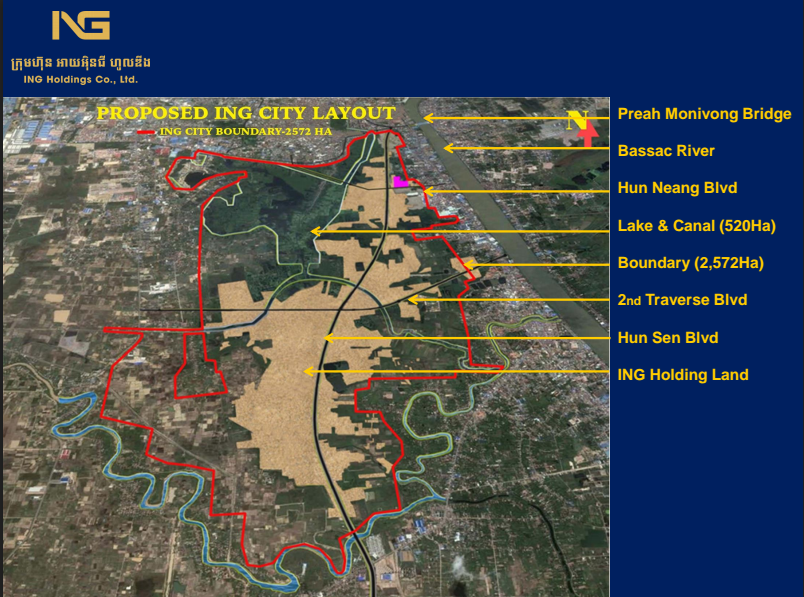

The well-connected conglomerate ING Holdings has been filling the 2,600-hectare site with sand since 2011. The company’s website shows its plans to incorporate much of the lake into a massive, 2,572-hectare “ING City” located south of Phnom Penh, leaving only a part as a “natural water reservoir.”

That imperils the hundreds of families living on or near Boeng Tompun, many of whom use the lake’s nutrient-rich water for farming, some of whom could lose everything—the water mimosa, their homes and their livelihoods. The lake is set to become Phnom Penh’s largest land dispute since Boeng Kak, according to Soeung Saran, executive director of housing rights NGO Sahmakum Teang Tnaut.

“Based on our research, around Boeng Tompun area…1,800 [people] will be affected by the development,” Mr. Saran said.

Complicating matters further, the lake in the city’s Meanchey district is also the lynchpin of a plan developed by the Japanese aid agency to solve the city’s impending sewage and drainage crises.

The plan relies on using part of the lake to build the capital’s first sewage treatment plant, but that goal appears to be threatened by both the ING development and what residents of the lake describe as a rush by others to gobble up northern swaths of the lake.

ING has its own plan to manage waste from the project’s estimated 300,000 residents, according to documents on its website and a report from the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA). Many of Phnom Penh’s “satellite cities”—large suburbs that are often built by private companies and can house thousands or tens of thousands of people—manage their own sewage, contributing to the piecemeal disposal system in the capital. That makes it difficult to fully grasp the full picture of sewage in the city, JICA’s report notes.

For Sut Kimlin, who lives in a metal shack with her husband and infant daughter on the north side of Boeng Tompun, it doesn’t matter whether the city or ING ends up with the lake—either way, her livelihood and home will likely disappear.

Ms. Kimlin makes less than a dollar a day growing water mimosa on the lake’s surface. Currently, she farms directly over the spot where JICA proposed—in an exhaustive December report to City Hall—to build a $450-million sewage treatment plant.

“If they build on our land, we won’t have anything to feed ourselves,” Ms. Kimlin said, squatting on the lake’s edge. Her father has been living on the lake for decades, farming vegetables on the water to sell in Phnom Penh, and she took over the job a couple years ago.

“We are worried,” she said, looking out at abandoned homes that sit several hundred meters inside the lake. “I’ve seen people leave their homes, but I don’t know if they were evicted or decided to leave.”

Ms. Kimlin lives in a slum with about 10 other families, in shacks built up on the lake’s edge. Her neighbor, 60-year-old Ngoem Kuoy, has lived there for the past 20 years.

Ms. Kuoy claims that in the past few years, land inside the wetland lake has been purchased by individuals, most notably Deputy Prime Minister Men Sam An. Ms. Kimlin also mentioned Ms. Sam An, saying that she pays rent for her farm to a man claiming to be a representative of the deputy prime minister.

Ms. Sam An, a longtime ally of Prime Minister Hun Sen, said she was too busy to talk to reporters after multiple requests for comment.

A towering, three-story house within sight of the lakeside shacks is owned by royal palace official Men Vuthy, who also owns parts of the nearby lake, according to neighbors and men who answered the door at the home.

Oum Daravuth, an adviser to the royal family, confirmed that Men Vuthy works as the head of the finance department at the Royal Palace, but declined to give reporters his contact information. Mr. Vuthy could not be reached for comment.

City Hall spokesman Met Measpheakdey denied that any part of Boeng Tompun had been sold by the city.

“Everywhere in Boeng Tompun belongs to the state,” he said.

However, information on ING’s website suggests otherwise. In an overview of the ING City project, the company states that “ING enjoys the benefits of owning the largest land share in the development.”

It says ING owns approximately 45 percent of the new city project and also acts as the management committee for the entirety of the project, including the 520-hectare section of lake and canals.

The project, it says, is “fully supported and approved by the Cambodian government.”

Contacted by telephone, ING’s investment and development director Simon Vancliff said he had “nothing to say” and did not respond to emailed questions regarding ING’s ownership of the lake.

The company’s three well-connected founders—Ing Bun Hoaw, a former CPP secretary of state at the Transport Ministry; Lim Rose, owner of the country’s largest cement factory; and Lim Bun Suor, the longtime director of the influential AZ Group, which was founded by Mr. Bun Hoaw—could not be reached for comment.

A map of the proposed ING City project, the largest development in Cambodia, on the company’s website highlights all of Boeng Tompun as part of the planned satellite city.

Phase 1 of the development features a 150-hectare “government city” to house ministry headquarters, a gated community development, “Villa Town,” transport and automobile hubs and a Japanese medical complex. There is also a plot for an amusement park, with ice skating, and a water park.

In April, the company completed construction on Hun Sen Boulevard, a major thoroughfare to the proposed city site that was inaugurated by the prime minister. In a “sponsored story” advertisement published in both The Cambodia Daily and Phnom Penh Post, ING says the road was built on land “reclaimed from the Choeung Ek wetlands.”

Concerns about evictions and forced removal of residents who previously lived on the route were raised as early as 2011.

According to ING’s plans, only a portion of Boeng Tompun would remain a reservoir. Mr. Saran, of the housing rights NGO, wondered why the city would allow the lake to be filled in at all, “given that Phnom Penh has been experiencing floods.”

“It would be good if they keep the whole lake as a reservoir,” he said.

Phnom Penh has long suffered from major flooding that shuts down entire sections of the city during rainy season. Newly appointed Phnom Penh governor Khuong Sreng used one of his first speeches to highlight the issue as a priority, and former Phnom Penh governor Pa Socheatvong took a similar approach last year.

Despite the oratory, progress on fixing the issue has been slow. Mr. Measpheakdey, the City Hall spokesman, said that a municipal working group was still studying JICA’s plan and it had not been finalized yet.

“Currently we focus on the areas where there is serious flooding. Then we will move them and replace bigger drainage,” he said, declining to elaborate.

JICA’s report is more detailed than a directive to build larger canals. In addition to people’s homes, Boeng Tompun’s development threatens a key part of JICA’s long-term plan to solve the capital’s sewage and drainage problems.

The report identifies a problem that many city residents struggle with regularly—much of the western and northern sections of the capital are located in “inundation zones,” which flood multiple times each rainy season, largely due to underdeveloped sewage and drainage systems.

Back in May, residents in Svay Pak commune, about 9 km north of downtown Phnom Penh, awoke to find foul-smelling black water pouring directly into the river. It flowed in a stinky stream between wooden homes raised on stilts, killing thousands of fish and polluting the area.

“It smelled like sewage,” Mann Ream, 65, who has been farming fish in cages beneath her floating home since 1979, said at the time.

Ms. Ream and dozens of other fish farmers had no choice but to flee the area, towing their wooden homes downriver with them.

Residents in the area had seen it all before. The stream and sewage smell was a constant in the neighborhood, going on for three or four years, according to Sok Pov, 30. “The smell gets worse when it floods in Phnom Penh,” he said.

Mr. Measpheakdey, the city spokesman, said at the time that the fish deaths were due to climate change and not related to sewage, citing unnamed experts.

Currently, the capital’s pipes and drainage canals bring most of the sewage and water south, where it is dumped directly into one of the city’s wetland lakes—including Boeng Tompun and the contiguous Choeung Ek lake.

The lake, along with the farmers who grow vegetables on its surface, the roots of which purify the water, serve as an effective sewage treatment method in the absence of a more sophisticated plant, according to Taber Hand, director of the NGO Wetlands Work.

“The wastewater is treated by microbes—a complex community of bacteria, virus, fungi, protozoans and other very small organisms that feed on the organic matter of the sewage,” Mr. Hand said in an email. “The water can be treated to a high quality by these root-based microbes.”

It’s a low-cost solution for the capital’s sewage, but the free ride won’t last much longer. The problem, Mr. Hand said, is that as lakes are filled in and the city’s population grows, the wetland lakes’ processing capacity is eroded while the amount of sewage needing treatment grows.

Peter Vos, head of the water sector at the NGO Global Green Growth Institute, agreed with Mr. Hand, noting the problem is becoming more pressing.

“Though an urgent problem and a high priority for government, the complicating factor is that building sanitation systems cannot be built very quickly,” Mr. Vos said. “These sorts of investments…take time.”

JICA’s plan gives the city time. Its proposed timeline for the main sewage treatment plant at the Boeng Tompun/Choeung Ek area schedules construction to begin in 2023.

But the plant’s site overlaps with ING’s proposed satellite city, and residents in the area say City Hall does not own the land where the treatment plant is scheduled to sit—though it’s not clear who does—all of which raises doubts about whether the fruits of JICA’s labor will ever be realized.

In an email to reporters, JICA program officer Soun Veasna said the report was produced at the request of the government and declined further comment.

“JICA is not in position to make comments on issues related [to] land use,” Mr. Veasna wrote. “It is to be decided by the Royal Government of Cambodia.”

In addition to the Boeng Tompun treatment plant, JICA’s report makes several other suggestions that reveal City Hall’s challenges in developing its sewage and drainage system.

“Disorderly reclamation of lakes, swamps, and wetlands, has reduced regulating capacity of stormwater,” it reads, adding that private developments and a lack of regulations or legal framework make a unified sewage management plan difficult to implement.

At the time the report was written, it said there were six engineers working for the drainage and sewage department of the Transport Ministry’s department of public works and transport, which is the government body primarily responsible for the city’s sewage and drainage. That’s not enough, particularly since none of them are qualified to operate a sewage treatment plant, the report says.

Other concerns highlighted by the report included the lack of a law governing sewage or drainage management, and an incomplete map of the city’s drainage and pipe system.

The public works department works in tandem with the Phnom Penh Water Supply Authority to manage the drainage system, but the authority is listed on the Cambodia Stock Exchange and is already in debt to multiple international aid agencies, making it unlikely to invest in an expensive, long-term project like sewage overhaul, according to the report.

For now, the money to be made on developing the lake appears to outweigh the concerns over the city’s increasingly precarious relationship with water and sewage.

Whether Boeng Tompun ends up in the hands of ING, City Hall or other private developers, it seems likely residents of the lake will be forced to find a new way to make a living.

Looking out over the lake, Ms. Kuoy shook her head. “They’ve bought it all,” she said

“They buy it and they keep it…. There’s no free land left.”