When voters go to the polls on Sunday, they will be selecting local representatives who, according to the 2001 commune law, are entrusted to serve the “general interests” of their communes.

Commune councils have always been intended to govern local affairs—at least in principle. But from their very inception more than a century ago, those running the country have used them more for political purposes than to meet the needs and welfare of residents.

And while commune council elections are the country’s oldest democratic ballot, the idea of giving ordinary people a voice in their own affairs did not arise from Cambodian rulers.

When the French took over administration of Cambodia after signing the Protectorate Treaty with King Norodom on August 11, 1863, they were puzzled by the country’s local management structures—or lack of them.

“They were coming from a world in which notions of commune or village were quite specific,” says French anthropologist Fabienne Luco, who has conducted and published research on Cambodia since relocating to the country in 1993. “In Cambodia, they found themselves facing something they had problems grasping.”

Villages consisted of a few homes built out of fragile wood and leaves, which could be abandoned and rebuilt at will, she says. This made for a “fluid universe” that presented difficulties for the French in terms of security and administration.

In earlier days, according to Ms. Luco, “The king had every right and lower-rank people every duty.” The old Khmer word for “govern” is “soy reach,” that is, “consume,” which meant that it was the people’s duty to “feed” the king through their

labor.

The king owned all the country’s land back then, but, unlike today, the land itself was worthless.

“What made a location valuable was the population living there and controlled by the king, as all the fruit of their labor would be his,” Ms. Luco says. “So people had learned that the farther they lived from central power, the better off they

were.”

Hence, their homes were built of transient materials, so they could move at a moment’s notice if the need arose.

Nevertheless, the French were determined to set up an administrative structure to better control the country and also collect taxes. Inspired by the democratic spirit of the Third Republic regime in France—the government system in place from 1870 to 1940 that supported France’s “civilizing mission” in its colonies—the French administrators set up communes, or “khum,” and decreed that each commune council’s members would be elected by the population to represent them at the provincial level.

The royal ordinance on administrative divisions, including communes, which King Sisowath signed into law on June 5, 1908, stated that every “inhabitant of a commune registered in the personal tax list,” that is, the head of household, could vote. This meant both men and women, even though, at the time, women were not allowed to vote in France.

“This showed the French administrators’ idealism, believing that they would be able to transfer to Cambodia something that was still new in Europe,” says French historian Henri Locard, who has lived in Cambodia for decades, researching and writing about the country’s 20th century history.

It was not until 1945, shortly before the end of World War II, that women would vote for the first time in France.

So the commune elections became the first ever national elections open to ordinary villagers in Cambodia, a country that had been ruled for centuries by monarchs with absolute powers.

It was not all smooth sailing.

At times, French and Cambodian officials were known to try to influence voters in the best tradition of democratic elections. And the process went through some adjustments, Mr. Locard says. The French put the “khum” through five reforms up to 1941 to improve procedures without altering its concept.

During the French Protectorate, commune elections were held every four years or so until December 1941, when France’s Vichy administration—allied with Japan and Nazi Germany during World War II—abolished them and let the provincial authorities appoint commune officials, taking away the people’s ability to choose their local representatives.

From the 1950s onward, the commune council’s role would be altered according to the country’s political situation. Following the country’s independence in 1953, King Norodom Sihanouk did not reinstate the commune elections during his one-party regime.

“Having other concerns and, one must admit, absolutely unaware of the vital importance for a nation of the grassroot entity that is a commune, no democratic reform really saw the light of day,” wrote Nhiek Tioulong, one of Cambodia’s most prominent statesmen of the 1960s.

“And yet, all it would have taken would have been to reinstitute the procedure set up [by the French administration],” he wrote in an unpublished manuscript obtained by Mr. Locard.

Then came the 1970s, with a civil war followed by the Pol Pot regime, a decade that saw every semblance of normalcy progressively disappear.

In the 1980s, once the Vietnamese army with a Cambodian battalion had removed the Khmer Rouge regime and taken over the country’s administration, the commune councils dealt with security and a country at war.

During this time, candidates had to be members of the People’s Revolutionary Party of Kampuchea—renamed the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) in 1991. As Australian historian Margaret Slocomb writes in a study, neither “the local nor the national elections made any pretence of standing candidates who were anything other than loyal to and trusted by the regime.”

Keeping in line with this, during the National Assembly debates on the commune administration bill in early 2001, the CPP insisted on only allowing councilor candidates who were political party members, eliminating the possibility of independent candidates. Moreover, the CPP ignored critics who deplored the fact that, according to the law adopted in 2001, commune councils are virtually overseen by the Interior Ministry, which also assigns a clerk to each.

As Ms. Slocomb points out in her 2004 study, “Commune Elections in Cambodia,” published by Cambridge University Press in the U.K., “the commune clerk has responsibilities similar to those of the former People’s Revolutionary Committee,” as commune councils were called in the 1980s.

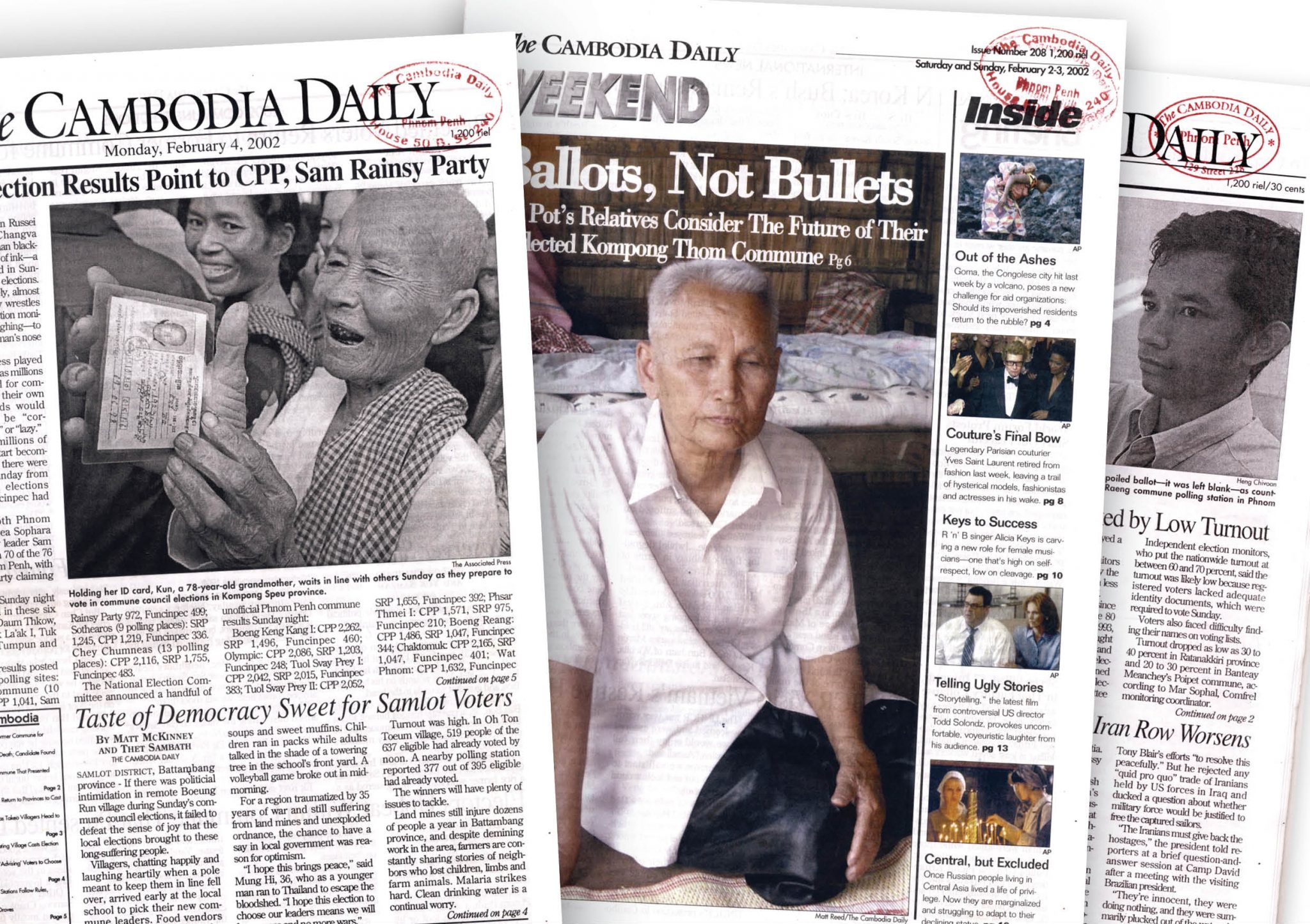

The CPP spent the 1980s building its network through commune councils, which is why observers were not surprised when the party delayed until February 2002 the commune elections slated for 1997, as they were convinced the CPP would never give up control of the communes, Ms. Slocomb writes in the study. The 2002 campaign was marred by violence and bloodshed, with at least 17 political activists or opposition party candidates killed prior to the elections.

“In the 1990s, in the areas [in Cambodia] where I was working, many commune chiefs had been put in place [in the 1980s] by the People’s Republic of Kampuchea,” says Ms. Luco, the anthropologist.

In the 1980s, she says, “the regime needed people to control the population. Therefore, they were selecting former Khmer Rouge [as commune officials and village chiefs] not because they were Khmer Rouge, but because people feared them.”

“Some of these village chiefs are still in place—a few of them would love to step down but can’t risk displeasing the CPP,” Ms. Luco adds

While village chiefs are public servants assigned by the government, commune officials continue to be elected, and commune elections since the 2000s have brought welcome changes, she says.

“People did not re-elect those they did not like or who were not doing a good job…People have more political maturity nowadays: The old tricks no longer work.”

And yet, because of the terms of the 2001 commune elections law, commune council members still have little choice but to do what they are told by their parties, if only because of the clerks who attend their meetings report to the Interior Ministry—a situation reminiscent of the government control structure in place during the 1980s.

Party control begins at the polling station, as voters must vote for a list of candidates selected by political parties, with the commune chief candidate also selected by the parties appearing at the top of the list. This makes it impossible for a candidate with no party affiliation to run for office.

Once elected, council members must vote according to their party’s directives. “Because, according to our law, if they are removed from the membership of the party, they automatically lose their position as commune chief or commune councillor,” says Koul Panha, executive director of the Committee for Free and Fair Elections in Cambodia.

“Sometimes…the party itself dismisses them or pressures them to resign. So immediately, they are finished,” he explains.

“That’s why the commune councils, the commune chiefs, they are so afraid. At times, they don’t feel comfortable advocating to influence decision-making…the reason why they are not active, not doing some advocacy or trying to do something…to be heard at the national

level.”

This truly hampers their work, as the government is very slow at implementing its decentralization policy and releasing the commune-project funding they need, Mr. Panha adds. CNRP leader Kem Sokha addressed this issue last week when he reiterated his party’s pledge to give every commune an annual $500,000 budget if it wins next year’s national election, decentralizing the commune system.

Currently, government officials don’t often listen to commune council members or really respect them, Mr. Panha says. “And yet, they are elected officials. They should respect them, you know, and there should be some kind of immunity for them, or at least the party should not have so much power, control over

them.”

After all, not only are they elected officials, they are the officials closest to the population. They are the ones the people turn to for civil administration documents, to witness property transfers, and to discuss local roads or natural resources. They also recommend district and provincial councilors.

“People really connect with them,” Mr. Panha explains.

As historian and political scientist Chheat Sreang says: “The level of authority is very local: literally. They’re working with villages throughout the country.”

One of Mr. Sreang’s studies in 2014 showed that, in spite of often being caught between the CPP government’s orders and their constituents’ needs, urban commune councillors have done quite well for their constituents.

“With modest resources of a few administrative staff and a meagre budget, sangkats [urban communes] have played an important role in the development of small-scale infrastructure in their localities,” he writes. “This is even more remarkable considering that projects can take several years to complete, as the cost often exceeds the sangkat’s annual budget.”

Mr. Sreang, program manager for the Center for Khmer Studies, has conducted research on communes from the 1890s to today.

With this month’s commune elections, he hopes commune officials will eventually be able to play a bigger role in their communes’ development.

“People should learn from history but, at the same time, should not attempt to move back to where we were 100 years ago, or 1,000 years ago or maybe even 20 years ago,” Mr. Sreang says.

“Environment changes, people are changing…. The world around us changes. And so, I mean, in human history, the best way to survive and progress is to adapt to the environment.”

“We should take the lead in that adaptation,” he adds. History has shown that upheaval happens when there is a “disconnect” between a society and its leaders who, he says, “do not realize that society has evolved past them already.”

As can be seen during this political campaign, altering set ways can be difficult. “But you know, as you can observe different political parties, they are advocating for different roles of the local governments in development…At least, there is diversity in views,” Mr. Sreang says.

“It’s politics as usual still. But at least people start to have differing views of how to improve society. And again, you know, we should learn from history, what has happened…so that we can make things better.”

In the early 20th century, commune councils were meant to help maintain law and order and collect taxes. During the 1980s, they turned into local authorities charged by the central government with watching the population and preventing any enemy intervention, as the country was at

war.

Today, it has been nearly two decades since the last Khmer Rouge leaders surrendered in December 1998. And even though Prime Minister Hun Sen has predicted turmoil if the CPP does not win in the commune elections, a large number of voters have little or no memory of the Khmer Rouge era or the 1980s war between Cambodian factions.

And they get their information on Twitter or Facebook as much, if not more than, on CPP-friendly television stations.

What is very much at stake today for the CPP is retaining its network of influence, as the CPP does not have any qualms about privileging relatives and supporters for jobs or business. So money is at

stake.

Although there will be people trying to find out who voted for whom in each commune, researchers point out that voters are fully aware that they will be protected by secrecy when they cast their ballots in the 1,646 communes. And this gives them freedom to make their choice at the voting station.

So the rest will soon be history.