Shuhei Murakami plays guitar at his Phnom Penh bar Good Times. (Emil Kastrup/The Cambodia Daily)

It began with a friendly gesture. A woman reached out to a Japanese tourist who had not been in Phnom Penh a full day and asked him about his country. Her daughter was about to start at a university in Tokyo, she said, so she invited him to her home for a meal to learn more about his culture.

But when the tourist arrived, he found a “really strange man” waiting, a casino blackjack dealer who showed off a few of his tricks: counting cards, stacking the deck and gilding hands.

Once the tourist was sufficiently impressed, the dealer proposed a game: a wealthy woman from Singapore was coming over, and the dealer would stack the tourist’s hand to win hundreds, and then thousands, of dollars.

Shuhei Murakami, 25, now realizes he was a fly who felt flattered to be invited to a spider’s web for a meal. But two years ago, as a 23-year-old fresh out of Japan’s Nihon University, starting a worldwide adventure, Shuhei, who goes by Shu, expected honesty from this casino dealer he just met.

Instead, he fell into a snare that would leave him tethered to Phnom Penh for much longer than he intended.

The dealer had a reason for the deceitful game, he told Shu. His wife was hospitalized, and he needed money for lifesaving treatment.

Without fully understanding what he was getting into, Shu consented. His opponent arrived, and in a few rounds, the $200 the dealer supplied to him had multiplied to $800. The dealer had him lose a few hands to keep the wager-hungry woman from suspecting anything, but not without warning Shu to bet only a small sum.

Frustrated with her losses, the woman proposed a final game, examined her cards and put a $30,000 bet on the table.

The dealer quickly pulled Shu out of the room and told him they had to scrounge up a matching sum. Shu left to withdraw all of his savings—about $2,000—and the dealer said he would add the value of his house and goods to the deal. Shu looked at his hand, convinced he and the dealer would walk away with the win.

At that moment, the game shifted.

The woman asked to pause until the following day. The two sealed their cards in separate, signed envelopes, locked in a safe, along with their money and Shu’s iPhone. The woman had one key and the dealer had the other.

A motorist who was watching the game offered to drive Shu back to his guesthouse, and covered Shu’s face and eyes on the ride home, allegedly to protect the passenger from the dust. Shu assumed the gesture was offered in kindness, but the driver then abandoned him in an unknown city.

After hours of wandering, Shu returned to his guesthouse with just $40 in his pocket. The dealer called Shu on the Nokia mobile phone he was given to communicate with the game’s players, and told Shu he needed the $40 for interest on the loan he was taking out. Shu considered the request, but then refused. It was all he had left.

The dealer called one last time to explain that the Singaporean woman had returned and stolen all the money, the hospitalized wife had died and Shu was responsible for it all.

As Shu tells the story over coffee and juice at Feel Good Cafe in Phnom Penh, he shakes his head and chuckles at his naivete. He keeps his long hair tied back in a neat ponytail and wears a disposable face mask when he rides his motorbike, but just two years ago he wandered the city bedraggled, filthy and miserable.

The blackjack con left him broke and homeless in a country he only knew from travel guides. His round-the-world vacation careened to a halt, and he spent the next night sleeping on one of the concrete benches along the riverside.

To kill the empty hours, Shu read the Cambodia travel guidebook he bought before departing Japan, arriving on a section he had skipped while preparing for his trip: common frauds and scams.

The guidebook outlined Shu’s past few days: the kind offer by a stranger, the dealer’s impressive tricks, the tragic wife in the hospital, and the opponent with limitless funds.

He hadn’t read the pages, he said, because he “didn’t think that there would be such stupid people to be cheated.”

This, Shu recalls, is the moment he realized the true extent of the deception.

When he went to the Japanese Embassy to report his losses, the staff said they had received two similar reports in the past week. Going to the police would be useless, he decided, and the embassy advised him to get out of town.

But his fear—of admitting he had been conned to friends and family in a fiercely competitive and success-driven culture—kept him from contemplating an early return to Japan.

Besides, he couldn’t afford a night in a guesthouse, let alone a flight to Tokyo.

So Shu called Nam Tan, a young man he had befriended on a bus between Siem Reap and Phnom Penh, and accepted an offer to stay at Mr. Tan’s parents’ home outside the city. He stayed a week, until his friend found a Japanese businessman seeking an English tutor. Shu gave lessons to the businessman in exchange for a bed, food and a few dollars each week.

As time passed, he acquired more students and took other jobs, living off about $3 a day and saving the rest. His new friends offered him shelter, and he moved between multiple couches and floors, trying not to overstay his welcome.

After a few months, Shu had saved enough to buy a one-way ticket to Japan. Instead, he walked into an instrument shop on Monivong Boulevard and bought a bright red electric guitar for $80.

“I was just stupid,” Shu said with a shrug.

But the used guitar brought him closer to his dream of becoming a musician than a ticket home could. He had played guitar since he was young, and in a band throughout university, but never thought he would be able to make it in Japan’s cutthroat music industry.

In Cambodia, he thought, perhaps he had a shot at the spotlight. With more time than money, Shu practiced his chords and riffs until he was confident he could jam with another band.

It took him three attempts to walk into the infamous bar and music venue Sharky Bar on Street 126. The first two times, he stood in front of the entryway, then turned around and headed home, intimidated by the dark staircase.

When he finally entered Sharky’s, he walked to the stage during a break, where Pavel Ramirez, then a regular Sunday night guitarist, regarded him skeptically and asked, “Who the hell are you?”

“I’m Shu from Japan,” he replied.

The frontman, an avid anime fan, greeted him with an enthusiastic “konichiwa” and invited him to play. After that, Shu returned every Sunday night.

He had yet to attain the confidence needed to manage a band, organize a show or run his own bar, but Shu was inching closer to gaining control of the crowd and mastering the music scene. He also needed a paid job with regular hours, so he asked a bar manager at Sharky’s for a job.

“This place is messed up,” Shu recalled him saying. “You went to university. You’re from Japan. You should be doing something better.”

But Shu tried again, this time asking the boss, Michael “Big Mike” Hsu. Big Mike agreed to give him a chance and they sealed the deal with a bottle of whisky.

Sharky’s hardened Shu quickly. He said he often had to demand respect simply because most of the clientele did not expect to see an Asian man helping to run a grungy bar that served as one of the hubs of Phnom Penh’s music scene.

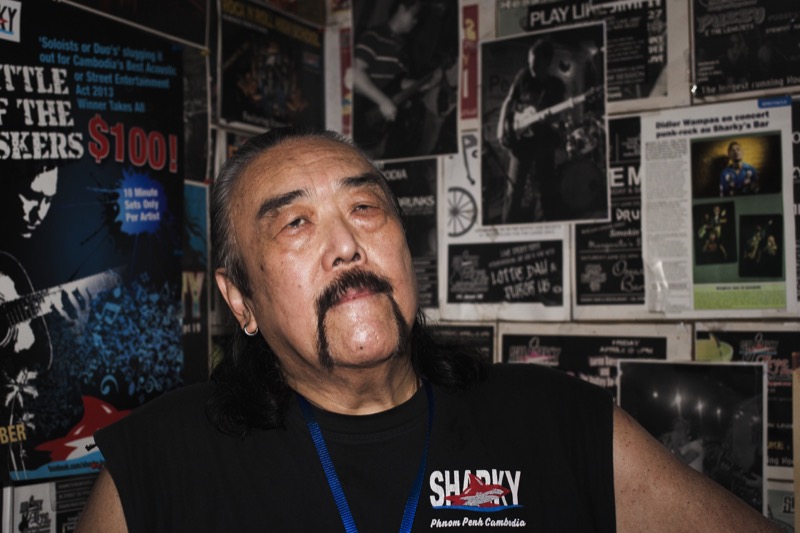

Michael ‘Big Mike’ Hsu, the late founder of Sharky’s bar in Phnom Penh, in 2015 (Jens Welding Ollgaard/The Cambodia Daily)

Big Mike, who had immigrated from China to New York City in the 1940s and then to Cambodia in the mid-1990s, had toughened to prejudice decades ago. Shu learned from his crazy stories of life as an immigrant.

When Shu started at the bar, he was quiet and found it difficult to talk to people. But he learned to cope with lazy performers, rude customers and brawling alcoholics.

“I don’t need to be good to people who are assholes. Sometimes I have to be an asshole to deal with people who are assholes,” Shu said.

Regular Sharky patrons, David and Hayley Flack, two expats from the U.K. who have lived and taught in Phnom Penh for 11 years, gush about Shu’s kindness and thoughtfulness in the gruff bar atmosphere, knowing their friend can swiftly diffuse conflict and dispose of a tricky customer, just like Big Mike.

“He’ll get customers that will just get a little over the top, and he’s a little soft spoken, but he can calm them right down and then get them out,” Hayley said.

After a year as manager, Shu left the bar at the end of May, just after Big Mike died, and Sharky’s was passed down to another shareholder. But before Big Mike died, Shu had a chance to tell his boss he wanted to start his own bar.

“I thought he would say, ‘oh so you want to be my rival, you want to be my competitor,’” he said. “When I told him about my ideas, he was OK.”

Good Times Bar on Phnom Penh’s Street 19 (Emil Kastrup/The Cambodia Daily)

Shu and a Japanese friend from university, Ryota Ito, took a lease on a former salon at #128 Street 19. They tore apart the small dividing walls, installed an Angkor tap and stocked the shelves with whiskey and sake.

Good Times Bar opened in August with an open jam session featuring Beatles songs. The cheap, cherry-red guitar Shu bought for $80 leans against the wall, next to a pale green bass given to him by Chris Hilleary, the host of Sharky’s open mics. The open jams have become a Monday night institution.

With its fluorescent lights and chipping white walls, some may pass over Good Times in favor of the tourist-laden bars with outdoor seating and $0.75 draft beers. But Shu’s lively presence keeps his friends and customers coming back, according to Scott Bywater, the host of weekly open jams and a well-connected musician in the city’s scene.

“He’s very well respected, and it goes beyond just showing up for support,” Mr. Bywater said. “You want to go in there because you know you’ll see people. You know it will be nice.”

Now that he’s found his footing in Cambodia, Good Times Bar’s modest proprietor intends to keep achieving. He’s formed some connections among Cambodian musicians, including Kan Pich, a Cambodian musician with a strong voice and a few songs, whom he met while he was sleeping on friends’ couches.

Shu wrote the music and lyrics to Mr. Pich’s song “Call Me Baby,” which was picked up by mobile operator Smart’s music platform.

Shu also hosts a radio show on Monday afternoons, backs up singer Joshua Chiang on guitar, and is planning to form a band so he can play guitar and drums more often.

More than anything, Shu said, he feels loyal to Cambodia for how residents opened their arms to him after his early struggles.

At his lowest point—his first night sleeping on the street—a homeless man approached him with a beer. Shu thought he had come to ask for money, but instead the man offered to share.

A bar like Good Times doesn’t pull in a lot of money, Shu said, but he will keep it running as a comfortable, friendly place with an open door.

“I owe a lot to this country for people, my friends, my family here, so I’m not going to run away.”

He shows his gratitude through his humble bar, a tribute and gift to his friends in the music scene who helped him during his couch-surfing days. When his friends in the band Road to Mandalay released their album in February, he sold band T-shirts and distributed flyers. When Mr. Bywater wrote a poem inspired by Good Times, he printed and displayed it behind the bar.

“I just wanted to make a place for people to hang out,” Shu said. “My friends are a part of my job, and I try to make them happy and I try to keep them entertained.”

Since the bar opened in August, Shu has rarely taken time off. Before the storefront lights up at 6 p.m., he’s busy with his odd jobs: tutoring native Japanese speakers in English, teaching baseball to kids, taking an emcee gig for an orchestra concert. Otherwise, he spends his hours at Good Times, pouring beers, hosting weekly themed conversations with Japanese expats or jamming during the open mic. He occasionally takes a gig elsewhere, but he always starts and ends his nights behind his bar’s counter.

Good Times has no stage, just a clutter of guitars, basses and stands. A well-known musician and music manager at Oskar bar, Mr. Bywater said he worried about the acoustics and the jam session setup, but Shu quickly proved he knew what his clients and musicians wanted.

“They just like the simple atmosphere and that it’s not pretentious,” said Mr. Flack, the U.K. expat. “They know he’s not going to pay them, but they just want to wind down after a gig and just play.”

Shu has aspirations of music and fame in Cambodia, but he hasn’t really thought about when—or if—he’ll return to Japan. Perhaps he’ll attempt the global trek once more. But right now, he’s making connections over a pint or a shot.

“It’s a small bar, but he’s also a young man. He’s still at the beginning of his career,” Mr. Bywater said. “I wouldn’t expect to come back in 10 years and see Good Times Bar still there, but only because it will have served its purpose.”

“But on the other hand, maybe it will be.”