On September 20, 1954, a 19-year-old Canadian civil servant sat down to write his father and brother a letter from his new home at the Hotel de la Poste in Phnom Penh.

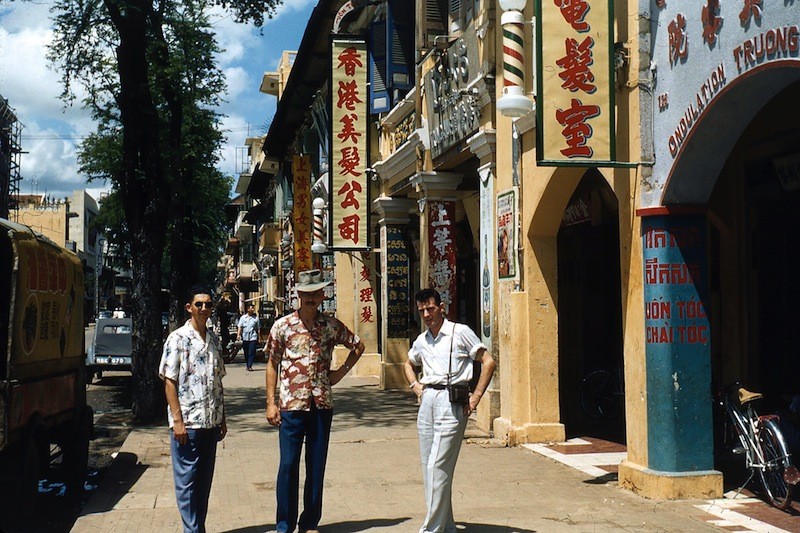

“P P is really the most fantastic city I have ever seen in all my life,” David Nixon wrote. “The climate is really very pleasant. Just like an average summer’s day in Ottawa.”

In June of the following year, Mr. Nixon wrote his father again. “I’m beginning to get very weary of the whole thing. It will be nice to get back into a good old ‘routine’ and be able to live with civilized white people again.”

By July, on the eve of his departure from the country, Mr. Nixon was nostalgic. “It’s been a fabulous 11 months and an experience I shall never, never forget—or regret—as long as I live.”

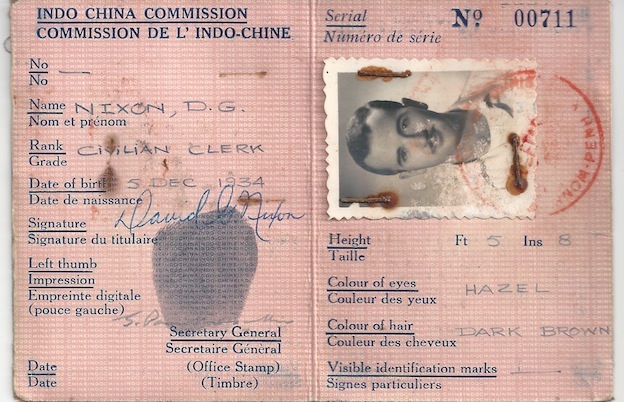

But Mr. Nixon did forget. He was dismissed from the foreign service as part of the Canadian government’s “queer purges” and underwent a series of electroshock and drug treatments—likely part of the covert CIA program MKUltra—that stripped him of most of his memories. In 2012, his husband, Ken Sudhues, transcribed and published Mr. Nixon’s letters and photographs on a blog he called “Our Mister Nixon.”

“He is in residential care and no longer knows who I am,” Mr. Sudhues wrote in an email. “I felt I had to share his stories far and wide, as he was no longer able to tell them or even remember them. His story is definitely worth sharing.”

Mr. Nixon began his stint as a stenographer for the International Control Commission (ICC) in Cambodia just two months after the end of the First Indochina War.

The ICC was a trinational force charged with enforcing the cease-fire between northern and southern Vietnam and overseeing the 1955 national election in Cambodia. With male administrative staff in short supply, the 19-year-old Mr. Nixon was able to secure a post normally reserved for much more senior diplomats.

The young man was characteristically ecstatic. “I am (no fooling) private secretary to the Acting Canadian Commissioner to Phnom Penh!” he wrote home to his family.

“Everywhere you look there are refugees fleeing the city with little bundles of personal belongings,” Mr. Nixon wrote after alighting in Hanoi on his way to Phnom Penh. Under the 1954 Geneva Accords, Vietnam was being partitioned into a communist north and democratic south, and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese living in the north were heading south. “Great mansions of the well-to-do Vietnamese have been left vacant and even after this short time you can see signs of deterioration,” he wrote.

He marveled at his office: the French doors, the palm trees outside his window and the monkeys trapezing through them. “I could just stand for hours and watch them, they are so much fun,” he wrote.

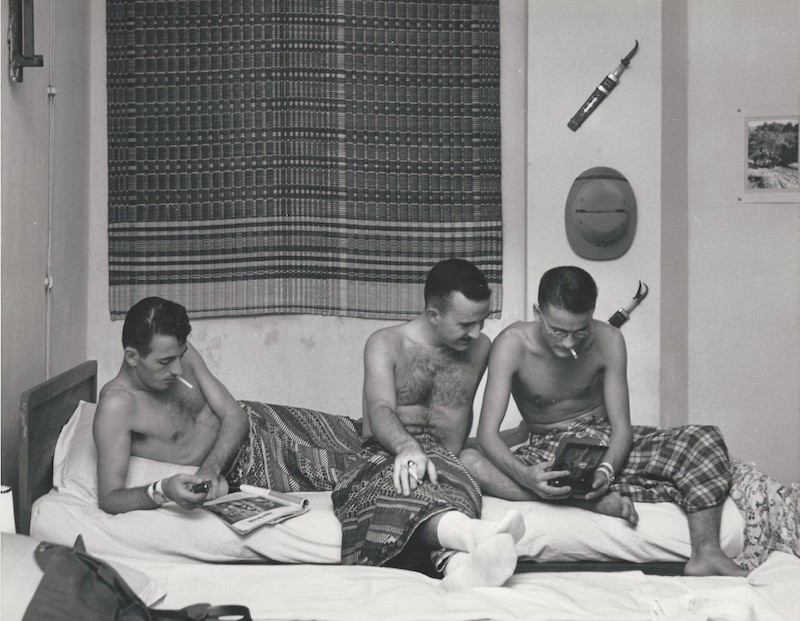

Mr. Nixon’s letters relate the ups and downs of his year in Asia with the exclamation-laden eagerness of today’s backpackers.

“WHAT A SIGHT!!!” he wrote after seeing the Silver Pagoda in Phnom Penh. “The entire floor was covered with thousands of squares of PURE SILVER!!!”

Mr. Nixon was less enthusiastic about Cambodians than the temples they had built. Arriving just one year after the end of French rule in Cambodia, his writing is punctuated by colonial-vintage racism.

After a junket up to Laos, for example, Mr. Nixon wrote that he had “come to the conclusion that they are just as lazy as the Cambodians—if that’s possible!!”

Such sentiments were likely common in the cozy expatriate haunts of his era and during his regular outings to movies at the U.S. ambassador’s house, swims at Le Cercle Sportif and weekend trips to Kampot. The bubble seemed to have kept him at a certain distance from the political actions of the day.

“I’d be most surprised if anybody, including the natives, would have the energy in this heat to start a civil war!!!” he wrote in May 1955.

Mr. Nixon finished his tenure in Phnom Penh and returned to Ottawa in July of that year. He went on to serve the Canadian Department of External Affairs in Bonn, Germany, followed by a stint in what was then the Belgian Congo.

In March 1961, a Royal Canadian Mounted Police official summoned Mr. Nixon to an office and ordered him to resign, according to Mr. Sudhues. The police said they had intelligence suggesting that Mr. Nixon was gay and therefore a security risk.

Sociologist Gary Kinsman has detailed hundreds of similar dismissals that occurred in the Canadian civil service and military during the first half of the Cold War.

“From 1958 onwards, LGBT people were identified as a major risk to national security,” Mr. Kinsman told Metro Toronto news last year. “We were described as suffering from a character weakness that made us, and I’m being a bit sarcastic here, vulnerable to blackmail by evil Soviet agents,” he said. “It expelled us from the fabric of the nation.”

Unemployed, depressed and unable to tell anyone about the reason for his dismissal from the foreign service, Mr. Nixon was referred by a psychiatrist to the Allan Memorial Institute in Montreal for more intensive treatment in 1963.

He emerged from the clinic in late 1964 a different man.

“He had little recollection of where he had been, who his friends were, where he had worked—it was all pretty much gone,” writes Mr. Sudhues on the “Mister Nixon” blog.

Mr. Nixon received some of his medical records in the early 1990s as part of a Canadian government restitution program. After reviewing the notes, Mr. Nixon’s doctor shook his hand and “congratulated him on still being alive,” according to Mr. Sudhues.

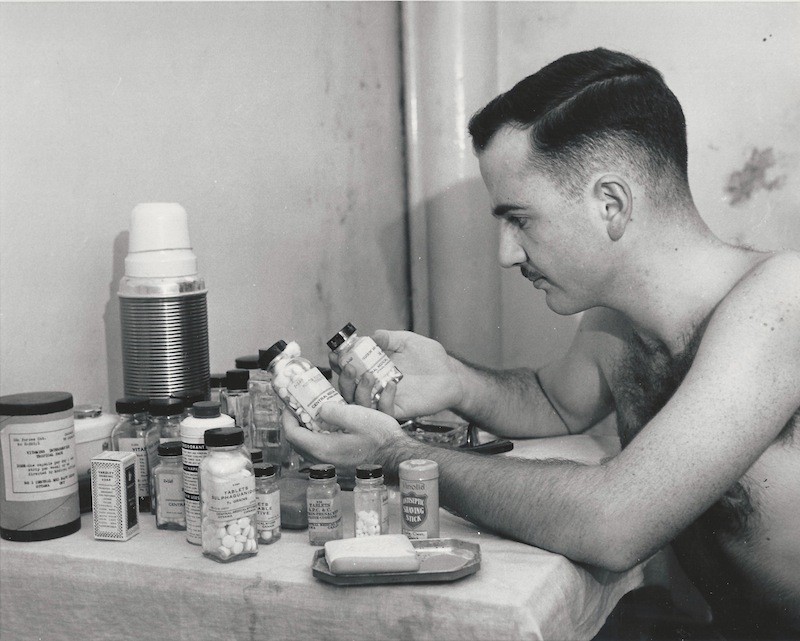

Mr. Nixon had survived “at least 36 electroconvulsive (shock) treatments in quick succession [and] was prescribed doses of drugs including Seconal that were far beyond the doses normally associated with treatment of depression,” Mr. Sudhues wrote on the blog.

The treatment closely matches that administered by Dr. D. Ewen Cameron, who, backed by the CIA, turned the Allan Memorial Institute into a “gothic house of horrors” for a group of 50 patients whose identities remain largely unknown, according to a January 1984 article in the Montreal Gazette.

Dr. Cameron led a Canadian wing of MKUltra, a covert program designed to “program new patterns of behavior” into patients’ brains using drugs, electrical shocks, sensory deprivation and other tactics, according to the Gazette.

Patients who participated in Dr. Cameron’s experiments were given heavy sedatives and awakened two to three times per day to receive electroshock treatments 20 to 40 times stronger than usual.

Dr. Cameron destroyed his files shortly before his death in 1967, making it hard to conclusively establish that Mr. Nixon was a victim of his experiments.

But Mr. Sudhues believes his husband was targeted by the program due to his “For Canadian Eyes Only” security clearance.

“Any time he ever tried to summon up memories or images of the work he did and the machines he used to do it, he said it was as if a hand appeared and pushed him away,” Mr. Sudhues wrote in an email.

Mr. Nixon slowly recovered from his time at the clinic and regained some of his memory and functional ability. He eventually moved to Victoria, British Columbia, where he met Mr. Sudhues in 1978 and went on to work for the British Columbian provincial government until his retirement in 1999 at the age of 65.

His memory problems accelerated in the early 2000s and he was diagnosed with dementia. In 2012, he was moved into a residential care facility, and Mr. Sudhues began sifting through his partner’s belongings and discovered the letters.

“He’d been planning to transcribe his letters himself when he retired, thinking there might be a book in it, but his dementia took away that opportunity.”

In undertaking the work himself, Mr. Sudhues hoped to pay “homage to David and his charmed/blighted life.”

It’s possible Mr. Nixon is still partially living in the worlds he left behind. As the dementia set in, Mr. Nixon described feeling that he was being transported to his past homes.

“He said that he’d been back in Cambodia or Germany and that it was so incredibly vivid that coming back into the here and now really jarred him,” Mr. Sudhues wrote. “Looking out our window in Victoria, he said he half expected to see the Rhine or the alley behind the Hotel de la Poste.”