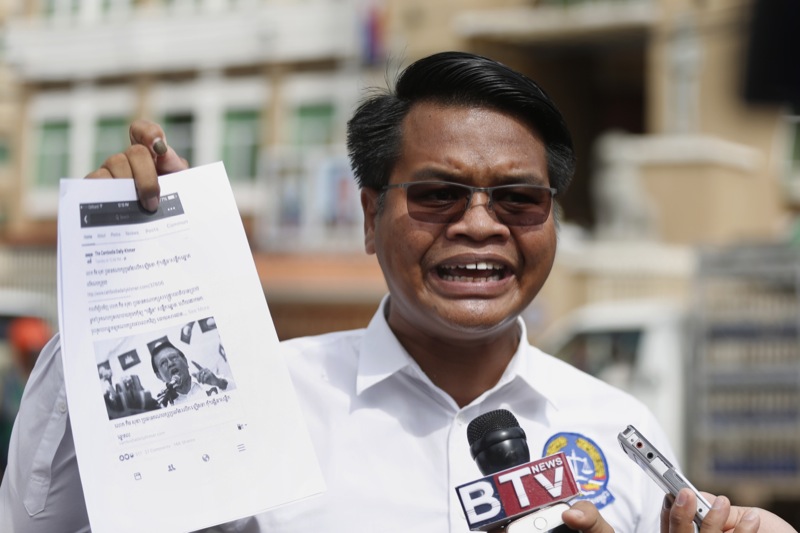

When Cambodian Youth Party President Pich Sros appeared last week at the Phnom Penh Municipal Court to sue his old boss, CNRP president Kem Sokha, few Cambodians knew his name, his political party or his motives.

That case against Mr. Sokha has thrust the 37-year-old marketer-cum-politician into a spotlight he never before enjoyed as head of the CYP, which received about 1,500 votes in the commune elections, or in a political career spent hop-scotching between opposition parties.

With legal experts questioning the legitimacy of the case, commentators and CNRP supporters have questioned whether Mr. Sros is working at the behest of the ruling party or merely angling for coverage of his new party.

Mr. Sros denies both accusations.

“I want Kem Sokha to look again, look back at the law,” he said in an interview last week.

The case centers on comments Mr. Sokha made over a week after the June 4 commune elections urging the electorate not to “waste” votes on minor parties, which Mr. Sros claimed incited voters to discriminate against his party.

In his lawsuit, Mr. Sros cited eight constitutional articles—none of which mentions discrimination against political parties—to support his claim that Mr. Sokha’s speech cost him supporters and votes.

Billy Chia-Lung Tai, a human rights and legal consultant previously based in Phnom Penh, said that incitement required encouragement to commit a separate offense.

“I would have thought encouraging voters to vote for another party really just falls in the realm of ‘campaigning,’” he wrote in an email on Thursday. “Given the way the CPP government has always used the judiciary, I would suggest strongly that this is really being done with the ‘nod’ or consent by senior CPP officials.”

Mr. Sros remains adamant that he is working for no one but himself—a position arguably supported by his brushes with past authority figures.

“I do this myself,” he said in the interview last week. “I do not need anybody behind me.”

Born to poor farmers in what is now Tbong Khmum province in the months after the Khmer Rouge regime fell, Mr. Sros said he migrated to Phnom Penh in 1997 to work as a construction laborer and later as a garment factory worker.

In 2004, he scraped together enough money to enroll in evening law school classes at Cambodian Mekong University of Phnom Penh, graduating four years later with a bachelor’s degree in law.

In 2006, Mr. Sros added a third activity to his busy roster by volunteering part-time with Mr. Sokha’s Human Rights Party (HRP), which he said he joined out of appreciation for Mr. Sokha’s work as head of the Cambodian Center for Human Rights.

But Mr. Sros soured on the party over the course of a year working both as a youth leader in Phnom Penh and a grassroots organizer in Banteay Meanchey province. Party officials said he was constantly late; Mr. Sros said he was just busy hustling between his two roles in the party.

“They got me wrong,” he said. “They kicked me out of the position in Phnom Penh.”

Ou Chanrath, a former secretary-general in the HRP, said he had only heard of Mr. Sros’ former involvement in the HRP after he established the CYP last year.

The lawsuit, he said, is “baseless,” but added, “it’s normal for some young politicians to want to try it.”

Mr. Sros quit his other role with the HRP in Banteay Meanchey in the months leading up to the 2008 election, eventually starting the United Organization for Progress (UOP) in 2010 as an outlet for his idealism.

The little-known NGO was a labor of love for Mr. Sros, who said he ran the organization for the next five years on weekends away from his paid job as a consultant marketer for car dealerships, soda makers and other companies.

The organization’s website says UOP exists “to build a better world for children” and claims that it “provides hope and assistance to about 14.4 million people” across the country.

Written entirely in English, the website is short on details of UOP’s activities. Instead, it offers bulleted lists like the “Impacts of Domestic Violence” as well as a logo and font that bear a passing resemblance to those used by the U.N.

A series of television clips and speeches show Mr. Sros speaking at a 2010 fundraiser for UOP co-sponsored by Smart Mobile and Sokha Phnom Penh Hotel, welcoming military and National Police officers to a 2011 “Ozone International Day” event, and addressing students at a 2013 National Institute of Education workshop.

Mr. Sros said on Monday that his work for the NGO included a broad portfolio of duties that included motivational speaking, educating audiences on children’s rights and doling out legal advice to needy farmers. The Sokha Hotel fundraising event turned out to be such a money loser, Mr. Sros said, that he had to live in a Phnom Penh pagoda until 2013.

The website also lists Truong Mealy, a former director of the Royal Cabinet and current adviser to the National Assembly, as head of UOP’s board of directors.

Mr. Mealy served as Cambodia’s ambassador to Japan in the 1990s and denied allegations that surfaced at the end of the decade that he was involved in the embezzlement of $700,000 during his tenure there.

In a series of exclamation-laden Facebook messages, Mr. Mealy offered vague answers to questions about his involvement in UOP and his role as what he called “senior advisor” to Mr. Sros.

“In those days, when I was still ACTIVE, I have promoted all activities which help the Khmer social and peaceful PROGRESS!” the 76-year-old wrote from France on Sunday.

Meanwhile, Mr. Sros said he had backed the CNRP, which formed in 2012, through the turmoil of the 2013 national election and ensuing protests.

Incensed by what he saw as relentless illegal immigration by Vietnamese nationals out to “steal my country again,” Mr. Sros resigned from UOP and asked to join the CNRP in 2015, reaching out to then-CNRP youth leader Hing Soksan. He said he was put off after Mr. Soksan failed to follow up on several scheduled meetings.

Mr. Sros said he went through a similar dance with the youth leader for Funcinpec before turning to radio personality Mom Sonando’s newly formed Beehive Social Democratic Party.

Mr. Sonando spoke highly of his former colleague’s character.

“He is a good person,” Mr. Sonando said. “He tells the truth. Sometimes when he tells the truth, it causes him to make enemies.”

Mr. Sros spurned age-based hierarchy, clashing regularly with then-Deputy President Heang Rithy, who has since left to form his own party, Mr. Sonando said.

After two months, Mr. Sros had had enough. “I check and I see that his team cannot do well because they always fight each other,” he said.

When he registered CYP with the Interior Ministry last year, Mr. Sros finally founded a party with which he could work, he said—one that could move Cambodia’s young population from the shadows of party elders who dominate decision-making in both major parties.

“I want all the youth to come out from politicians and do [development] by themselves,” he said.

Mr. Sros is, of course, also a politician, but says he’s receptive to any good idea put forward by young people.

He’ll likely need more ideas if the party hopes to have a future, as Mr. Sros’ platform, centered on solving youth unemployment and helping farmers, has attracted what he estimated as 50 active party members in Phnom Penh and another 600 in Tbong Khmum province.

Yim Seng Yean, a 45-year-old CYP commune chief candidate who received just 93 votes in the province’s Tuol Sophy commune, admitted that he had “no hope” the party would win any seats in next year’s election.

But Mr. Seng Yean, who defected from the CNRP about eight months ago, was optimistic about his leader’s long-term potential.

“Mr. Pich Sros is serious,” he said. “He won’t promise and then give up like others.”

The party is run on donated time and money from members, with Mr. Sros estimating he collects between $500 and $1,000 a month in donations.

Hang Vitou, head of a young analyst group, the Kem Ley Foundation, said Mr. Sros had told him that he had “no money to do politics” after they met four months ago.

Mr. Sros tried recruiting Mr. Vitou to join the CYP’s ranks, he said, but the analyst was reluctant.

“I think that this small party doesn’t have a clear platform,” he said. “I have noted that he always does something arbitrarily.”

Mr. Sros said he did not recognize Mr. Vitou’s name.

Mr. Vitou also shared public skepticism about Mr. Sros’ motives—ones that have, like all Cambodian political gossip, found an outlet via memes and posts on Facebook.

If the rich and powerful were really pulling the strings behind the CYP, the party would have done better in the last elections, Mr. Sros said.

“All the activities I do are for the nation, not for my own life,” he said on Monday.

Mr. Truong, his former NGO adviser, had a different take, describing the lawsuit as “a political maneuver” for “each and everyone’s private benefits.”

“Everything and everyone would be confused with the so-called Games of Politics!” he wrote.