Nuon Chea on Thursday broke his silence at the Khmer Rouge tribunal to refute claims that the regime perceived the Vietnamese as “hereditary enemies,” and asked an American academic whether he believed the U.S. bombing campaign in Cambodia during the Second Indochina War constituted genocide.

Testifying for a fourth and final day, Alex Hinton, author of the 2004 book “Why Did They Kill?,” was questioned by Anta Guisse, a lawyer for Khmer Rouge head of state Khieu Samphan, about speeches made by Pol Pot in April 1978, which were published in an edition of the regime’s “Revolutionary Flag” magazine.

On Tuesday, Mr. Hinton interpreted an excerpt—in which Pol Pot boasts that “not one seed” of the Vietnamese population remained in Cambodia—as a pronouncement of “successful genocide” against the Vietnamese.

Ms. Guisse on Thursday presented snippets from the article in which Pol Pot claims the Khmer Rouge “smashed the aggressor Yuon forces”—using a term for Vietnamese that can be derogatory in some contexts—and argued that the regime’s leader was talking purely in military terms.

Mr. Hinton responded that despite there being clear references to military conflict, the use of the word “Yuon” incited “hatred against ethnic Vietnamese in Cambodia.”

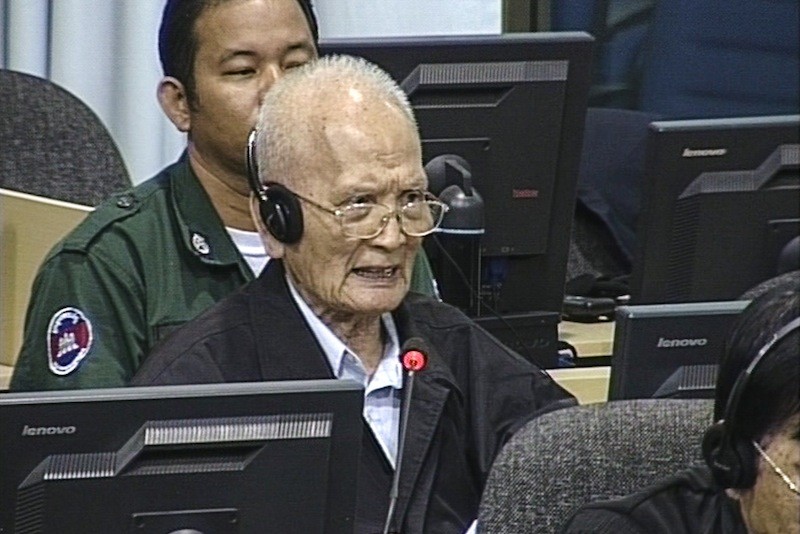

Nuon Chea, 89, then exited his holding cell—from which he observes proceedings due to his poor health—and took the stand to criticize Mr. Hinton’s interpretation of the word “Yuon” and characterization of the Khmer Rouge attitude toward the Vietnamese.

The regime’s second-in-command cited a 1967 dictionary authored by Chuon Nath, which states that “Yuon” is a noun referring to residents of various regions of Vietnam.

“So, Democratic Kampuchea did not mean to incite anyone, and the term is clearly defined in that dictionary,” Nuon Chea said.

“Actually, Pol Pot gave instructions to us that we should not regard them as our hereditary enemies. They were our friends, but we had contradictions with them and that is the expressed instructions of Pol Pot,” he continued.

Nuon Chea then asked Mr. Hinton whether the U.S. bombing campaign in Cambodia in 1969 and 1970 could constitute a war crime and genocide.

“You are an American citizen and you know that actually U.S. dropped bombs in Cambodia for 300 days and nights. And as a result, many houses, pagodas and infrastructure were destroyed, including the lives of Cambodian people. Do you consider that that is a crime of war…and genocide?” he asked.

Mr. Hinton conceded that the bombing had a devastating impact on Cambodia, and said it helped pave the way for the genocide carried out by the Khmer Rouge.

“Certainly, people have argued that…it might have violated international law, and it certainly had an awful impact. I think no one would contest that,” Mr. Hinton said.

“The bombing was part of a process of upheaval that combined with the CPK [Communist Party of Kampuchea] vision of society, ultimately, and unfortunately once people were labeled as class enemies, as subversives, as counterrevolutionaries buried within, [this] led to genocide,” he said.

The anthropologist concluded by defending his characterization of the term “Yuon.”

“In the end, I stand strongly by my stance that the word ‘Yuon’ can be a very incendiary word. It’s a word that can incite hatred and violence, and in the context of DK it was an incitement to genocide.”