In 1978, after three grueling years toiling in a village in Kompong Chhnang province under the control of the Khmer Rouge, Ung Phuon was returning from an assigned trip to catch fish when he was told by a local official that he was to be married.

“When I came back from fishing they told me, ‘You, comrade, go to prepare yourself for marriage,’” said Mr. Phuon, now 68, during an interview last week.

Knowing nothing about his bride-to-be, Mr. Phuon was brought to a house and ordered to sit on a bench across from a line of black-clad young women.

“When I walked, the tears were coming down because I had no parents beside me and I did not understand why I was being forced to marry,” he said.

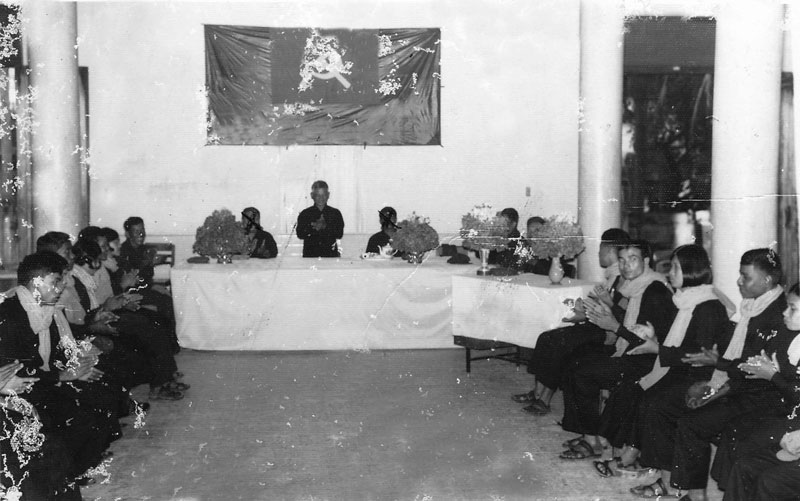

Barely able to discern the face of his new wife in the dimly lit room, Mr. Phuon and five other couples pledged their allegiance to each other and Angkar—the Organization, as Pol Pot’s central government was called—before being handed a traditional sticky-rice-and-bean dessert and sent to their new living quarters. He had seen his new bride around the village before, but they had hardly exchanged more than a few words.

Despite understanding the regime’s expectations for newlyweds to consummate their marriages—he had seen couples “disappear” for not “getting on well”—Mr. Phuon and his new wife, Mam Yet, did not have sex on their first night together.

“I did not touch her and I wanted to keep our purity because I thought I might not stay alive and she would become a widow,” he said, adding that it did not take long before cadre began questioning him.

“They investigated us and asked, ‘How was your consummation?’ I told them there was no problem and we were happy. I told my wife to say the same thing,” Mr. Phuon said.

Forced marriage, and rape in the context of such marriages, is the focus of a new book entitled “Like Ghost Changes Body,” which was released by the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Cambodia last week.

The book, which features eight case studies of Cambodians forced to marry during the Khmer Rouge regime, contains disturbing recollections, not only of abrupt mass marriage ceremonies, but of the surveillance and pressure newlyweds were subjected to afterward as the government encouraged couples to produce the next generation to serve its agrarian revolution.

After being forced to marry a man far older than herself, one 53-year-old woman tells of how, despite managing to deflect his initial advances, local Khmer Rouge guards, or “chhlob,” physically restrained her while her husband attacked her.

“The guards said it had been almost a week and we still had not slept together, so that night we had to have sex. I did not agree. I said I did not care if I was killed,” she says in the book.

“There were two guards, both women, and one of them is still alive today. They tied my legs and arms to the bed and then they moved away to let my husband approach me. And that f—ing husband raped me,” she said.

In another interview, a 57-year-old Cham Muslim woman explains how the fear of death at the hands of local cadre resulted in her giving up her virginity to her new spouse.

“We discussed together that night and agreed between us [to have sexual relations] because the cadres had threatened us, saying that if we didn’t get along that night, they would take us to be killed,” she said. “My husband said: ‘If we don’t get along, we will be killed as the chhlob are spying on us now.’”

The topic of forced marriage will come under scrutiny at the Khmer Rouge tribunal next year, when prosecutors will attempt to prove that the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) implemented a nationwide policy that forced people to marry and have sexual relations in order to increase the number of able workers.

“During the Khmer Rouge regime, many thousands of Cambodians were forced to marry under threat of re-education, imprisonment or death. To ensure a sufficient workforce, the CPK systematically monitored the newlyweds to confirm that they consummated the marriages,” William Smith, international deputy co-prosecutor at the tribunal, wrote in an email on Friday.

“The forced unions and traumatic conjugal relations that followed frequently left victims with permanent physical and/or psychological damage, and they were often forced to endure these associations not just once but over an extended period of time,” he said.

Theresa de Langis, a researcher on sexual violence who edited the new book, said the effects of forced marriages on victims have been deep and far-reaching.

“The trauma of having lost the opportunity to make a central life choice is mentioned in most interviews. The loss of human dignity and being treated as animals, ‘cows’ and ‘dogs’ put out to breed,” Ms. de Langis said.

“Faced with social stigma, [women] were often left to raise children on their own and many were unable or unwilling to marry again. One interview describes the pain of being excluded in some cultural rituals because women who are divorced or widowed are considered ‘bad luck.’” she said.

Despite the prying eyes of the local soldiers, Mr. Phuon and Ms. Yet managed to avoid having sexual relations until the Vietnamese forces overthrew the Pol Pot regime. Separating briefly, the couple then decided to stick together. It was only then, after they had chosen each other of their own free will, that they consummated their marriage.

However, Mr. Phuon said the consequences could have been different.

“If we didn’t accept this marriage, they would have moved us far away from our place and nobody knew where that would be,” he said. “No one dared to argue with these marriages. Of 100 couples [in the cooperative], 100 agreed.”