During a recent post-rain rush hour, a tuk-tuk driver who identified himself only as “David” sat in his vehicle, reading a newspaper and watching the traffic on Street 51 snarl past.

The problem, David said, was that Cambodians flagrantly disobeyed the law.

“The space is free, you go,” said David, 52, who claimed that in addition to being a driver he was also a police officer. “The opposite side is free, you go.”

With the number of vehicles on the road increasing, David had little hope the government would be able to fix the situation.

“The vehicles are so many, and the roads are very small,” he said.

David’s fears are widely shared in the capital, where experts warn that soaring population, vehicle use, condominium construction, minimal enforcement of parking and vehicle tax laws and lackluster public transit options could spell decades of gridlock if action is not taken soon.

“Paradise doesn’t wait for us,” warned Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) senior representative Takashi Ito. “The best strategy is to plan long and implement fast.

JICA’s 2035 master plan for urban transport in the capital, which would cost $4.56 billion if implemented, calls for a range of new measures, including four driverless train lines, seven new bus lines and road and traffic management improvements.

But many of these proposals remain unfunded and may never be, Mr. Ito conceded. And even with these improvements, Mr. Ito warned that the best the city’s residents—estimated to swell to 2.87 million by 2035—can hope for is that traffic stabilizes before it crests to Jakarta levels, the kind of traffic in which “you are immobilized in the car for hours.”

In Jakarta, “weak governance and institutions have been a root problem,” according to Robert Cervero, chair of city and regional planning at the University of California, Berkeley.

“For the past three decades, Jakarta has been in a reactionary mode, responding to crises with short-term traffic engineering fixes as opposed to strategically planning for future growth,” he said in an email.

JICA hopes that by offering Phnom Penh authorities what Mr. Ito calls a “comprehensive package” that reflects years of careful research, the agency can steer Phnom Penh away from that fate.

“What we are afraid of is to do something…immediately, without deep reflection,” Mr. Ito said.

Authorities have made it clear that they take a different view of the situation.

In January, JICA was blindsided by Prime Minister Hun Sen’s announcement that the government would build a new expressway to the airport—a road that had not been included in the 2035 master plan.

Mr. Ito said the expressway would have thrown off carefully calibrated research that went into the 2035 plan had it not been abruptly canceled last month.

Transportation Ministry spokesman Var Sim Soriya said the government viewed the master plan as a recommendation rather than a definite blueprint and needed time to carefully consider the proposals.

“We understand that Japan wants to develop our country,” Mr. Soriya said. “However, the investments they’re asking for are big, so in our capital, we need to think more before implementing it so that it does not cause more problems.”

Phnom Penh municipal governor Pa Socheatvong said the master plan—an early version of which was first presented to City Hall almost three years ago—might not be approved anytime soon.

“They may have to wait many years because we have to see how much benefit the plan will bring and be sure it is done well,” Mr. Socheatvong said.

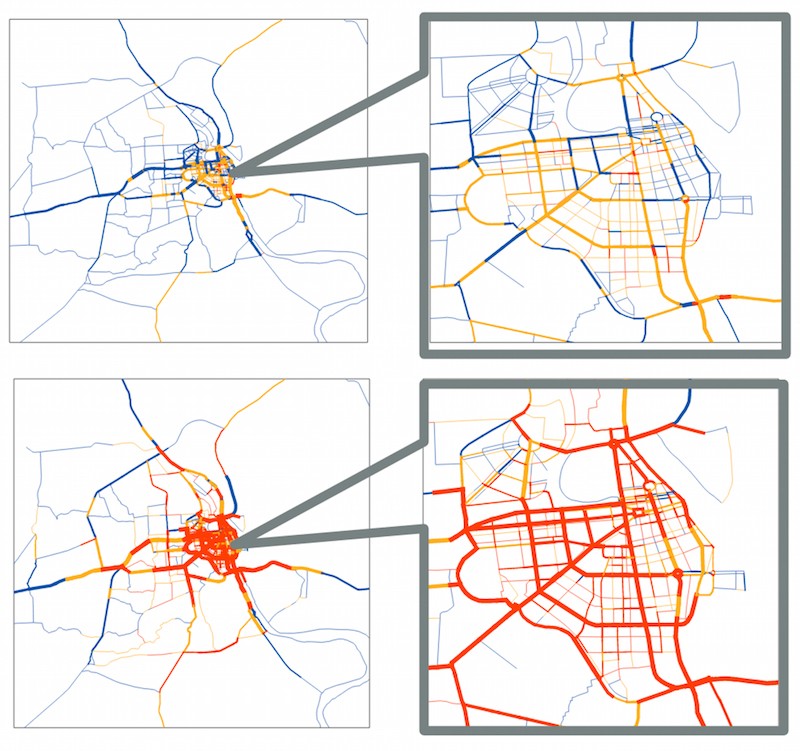

As City Hall deliberates, traffic is slowing. JICA research shows that speeds in the urban core of Phnom Penh slowed from 22.9 km/hr to 14.6 km/hr in the period from 2001 to 2012 (the last year for which JICA had available data). The number of vehicles registered grew by a magnitude of 3.5 during that same period.

Phnom Penh’s narrow roads weren’t built for today’s Land Rovers, many of which were imported illegally, according to the Cambodia Automotive Industry Federation.

“We are years behind in planning infrastructure,” federation president Peter Brongers said on Thursday. The situation is exacerbated by the 40,000 “gray market” vehicles that are annually imported as scrap to dodge high taxes—ten times the number sold on the legitimate market, according to the federation.

JICA is investing $15 million in synchronized traffic light signals and a traffic control center to help existing traffic flow. The 2035 master plan advocates building more peripheral highways as well as turning existing streets into one-way roads to avoid the SUV face offs endemic to contemporary Phnom Penh.

However, “only road improvements [are] not enough,” warned JICA adviser Aya Miura.

Phnom Penh’s compact center has the makings of a pedestrian-friendly core. But as tourists regularly discover, Phnom Penh’s sidewalks double as parking lots.

For five days in 2013, the city turned four east-west riverside roads one-way and barred sidewalk parking. The clearer streets allowed traffic flow to increase by 150 percent on Street 154, and more than 70 percent of roadside residents wanted the program to continue, according to JICA research. Instead, the experiment ended and traffic in those corridors reverted to their usual form.

Public transit could also make a dent in curtailing traffic, and some initiatives seem to show promise.

JICA is planning to spend some $18.5 million in grants and technical assistance to boost the existing three bus lines to ten and upgrade the bus fleet by 2020, greatly expanding coverage.

A 2014 survey of some 1,100 bus riders published in the Journal of Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies showed that almost 95 respondents evaluated the service as either “good” or “very good.”

Still, the survey found that bus riders objected to the long commutes that are a symptom of the very problem they are meant to address. City Hall should consider a “stricter policy about the on-street parking or priority lane for bus service” to speed up service, study author Veng Kheang wrote in an email.

And this week, Royal Railways CEO John Guiry said the company was considering running passenger train service on an existing line from central Phnom Penh to the airport, adding another possible public transit alternative to the capital.

The most technically advanced transit project on the table is a $586 million, partially automated train that would take a southern route from downtown to Phnom Penh International Airport, which JICA hopes to have running in roughly a decade.

Mr. Soriya was skeptical the city could find a clear path for the route.

“I saw that the Japanese requested [the] government to find land to build the tracks for a skytrain from Olympic Stadium to the airport, but where is there open land for development?” he asked.

Costs are another concern. Mr. Ito admitted that operating the line would be a money loser for City Hall, even as it brought in several hundred million dollars annually in broader economic benefits.

JICA plans on financing the building of the train with loans, but much of the remainder of the proposals in the $4.56 billion plan —including three more rail lines —will have to come from other donors and the private sector, according to Ms. Miura of JICA.

City Hall should understand that in order to avoid gridlock, “they have to spend some amount of money,” Mr. Ito said.

“We could do it at a reasonable price now,” he added. “Later, more expensive: that is the golden rule of urban planning.”

Without action, Phnom Penh is likely to suffer many of what Mr. Cervero of Berkeley describes as the ill-effects of congestion: “Stress (and bodily attacks from road rage), lost labor productivity (which lowers incomes, impinging upon wellbeing more broadly)” as well as decreased safety, and increased air pollution and traffic accidents.

A 2013 World Health Organization report showed traffic deaths on the rise in Cambodia, with the organization estimating 2,365 fatalities that year.

Mr. Soriya insisted that with stakes this high, the government should not be rushed.

“In order to approve the Japanese master plan, we need to discuss it for a long time with other ministries that are involved,” he said.

Mr. Ito disagreed.

“There is no magic stick,” he said. “We have to do something now…. Even by doing this, things will not be drastically improved.”