In August last year, The Asia Foundation launched three new smartphone apps designed to end violence against women and girls in Cambodia.

Created at a cost of $30,000 each, the free apps were an expensive bet that smartphone-savvy Cambodians would go out of their way to download programs explicitly designed to improve the safety of women.

Six months later, each app has been downloaded just under 400 times, according to Asia Foundation program officer Setha Rath. Funding from Britain’s Department for International Development has ended, leaving future promotion of the apps in limbo.

The Asia Foundation initiative is not the first app-based humanitarian effort to languish after launch. Transparency International’s (T.I.) Bribespot, which asks users to track and map instances in which they had been asked for a bribe, has recorded just 60 such cases since May 2014. And the U.N. and Agriculture Ministry-funded e-PADEE program has trained hundreds of volunteers to use tablet computers to provide advice to rice farmers, but faces an uncertain future as funding is curtailed.

“Not all problems have technical solutions,” said Channe Suy Lan, regional lead at InSTEDD Innovation Lab Southeast Asia. “The technology is flashy, but you have to see who you are targeting.”

To get in touch with its target population, The Asia Foundation borrowed the process and vocabulary of Apple and Google, which use so-called “human-centered design” to prototype products by vetting them with the demographic they hope will ultimately use them.

The foundation entrusted the “ideation” of the apps to several young activists, who conducted workshops with colleagues and clients to define and refine their ideas, according to Ms. Rath.

One of those activists, 24-year-old Sum Dany, who was a volunteer at the Cambodia Young Women Empowerment Network (CYWEN) in 2012 when she first participated in the process, came up with the idea for an app after meeting with women in rural areas.

“When I ask about domestic violence with people in the provinces, they say it is a normal thing that happens,” Ms. Dany said.

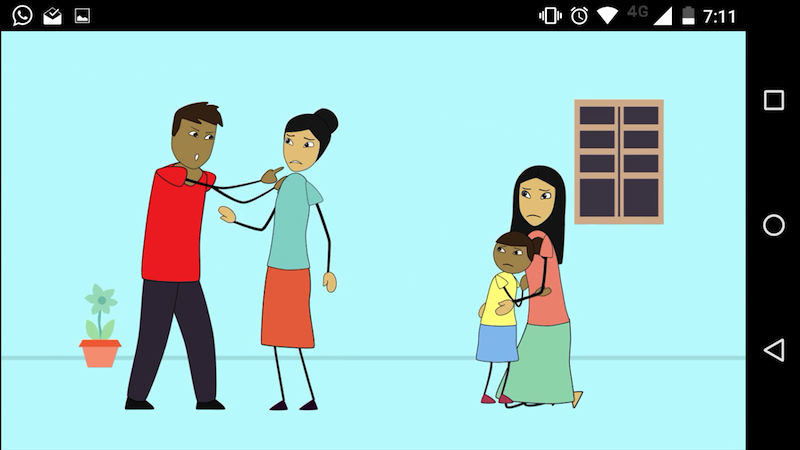

Following consultations with local NGOs, The Asia Foundation and its technical partners, Ms. Dany’s app Krousar Koumrou, or Model Family, launched in August with a series of chirpy animated videos intended to change widely held perceptions about domestic violence.

However, six months later, Krousar Koumrou and two other apps developed through the project have notched less than 400 downloads each.

Although the activists had researched their target populations, Ms. Rath said, “we didn’t know about mobile phone behavior.” She described a recent meeting with activists and NGO workers. “They don’t know about Play Store, they don’t have Gmail.”

“It’s a trend for funders to fund projects having to do with technology,” she said. But app creation, she added, “requires a lot of resources, especially to measure the impact.”

Ms. Dany said that while she had enjoyed the process of developing her app, it had been less successful than other, less-expensive NGO programs.

“I don’t think it’s the best way to spend money,” she said.

Transparency International has faced similar challenges in convincing Cambodians to use Bribespot.

The Khmer-language version of the app and website was launched in May 2014 in the hope that Cambodians would anonymously report when and where they are asked for bribes. The input is then geocoded and mapped on Bribespot.com.

But Bribespot has catalogued just 60 such reports in a country that, according to T.I.’s own research, is perceived to be the most corrupt in Southeast Asia.

Chin Ly Da, a lawyer at T.I.’s Advocacy and Legal Advice Center, said the organization initially promoted the app by giving users gifts in exchange for downloading it. Many walked away with the gift and a hazy understanding of the app, he said.

“When they download the app, we have to inform them why it is important to report corruption,” Mr. Da said, adding that the app played an important role in the organization’s five-year plan.

“That’s why we need to get more funds—to get more and more people to understand why to use the app.”

Maintaining momentum for donor-funded apps is a struggle familiar to Australian agricultural expert Stuart Brown, who consulted on a project funded by the U.N.’s International Fund for Agricultural Development, which is designed to improve the livelihoods of rice farmers using a tablet-based app.

The e-PADEE project trained a group of 167 Cambodian “entrepreneurs” to test soil and input the results into a tablet-based app. The entrepreneurs—who were not paid for their services—then used the app to advise farmers in five southeastern Cambodian provinces on which seeds, fertilizers and pesticides would produce the most robust crop.

During a presentation at USAID’s Phnom Penh office last week, Mr. Brown trumpeted the project’s headline metrics: 1,649 recommendations provided to farmers across 148 communes. An informal survey even suggested that farmers who had followed the advice saw increased yields.

The Ministry of Agriculture will continue to provide a small budget for the project in 2016 to cover software licences and some operating costs, according to e-PADEE project manager Goele Drijkoningen. But additional cash would allow the team to conduct a more thorough evaluation of the project and reach more farmers.

“Is there a champion that will drive this?” Mr. Brown asked the crowd last week. Convincing veteran Cambodian farmers, some of whom had been to “hell and back,” to trust the guidance of an app-wielding adviser would require sustained effort, he warned.

Still, Mr. Brown believes technological changes will reach Cambodian farmers as generational churn and labor migration force them to become more efficient. E-PADEE, he said, “isn’t a silver bullet, but it’s a start.”

Ms. Suy Lan of InSTEDD also remains cautiously optimistic.

“I think there is still room for an NGO to design technology to impact people,” she said. Over half of all Cambodians still don’t yet have access to Internet, she said, and Khmer-language devices have just started to gain traction.

The key, she believes, is to “design for the beneficiaries, not for the project.”