It was state security guards, under the jurisdiction of Phnom Penh City Hall, who finally rushed into a crowd of protesters last Monday after hours of simmering tensions between the crowd and police—pummeling an NGO officer and a land rights activist.

—News Analysis—

It was also City Hall that twice banned 100-day funeral ceremony plans for murdered political analyst Kem Ley—before reversing course on Wednesday—and rejected a request to place a statue of him in Freedom Park.

And when the CNRP asked to march to foreign embassies last month to deliver petitions calling for intervention in the deteriorating political situation, it was the city’s governor, Pa Socheatvong, who said no, explaining that the “city does not belong to the opposition,” according to a report from Fresh News.

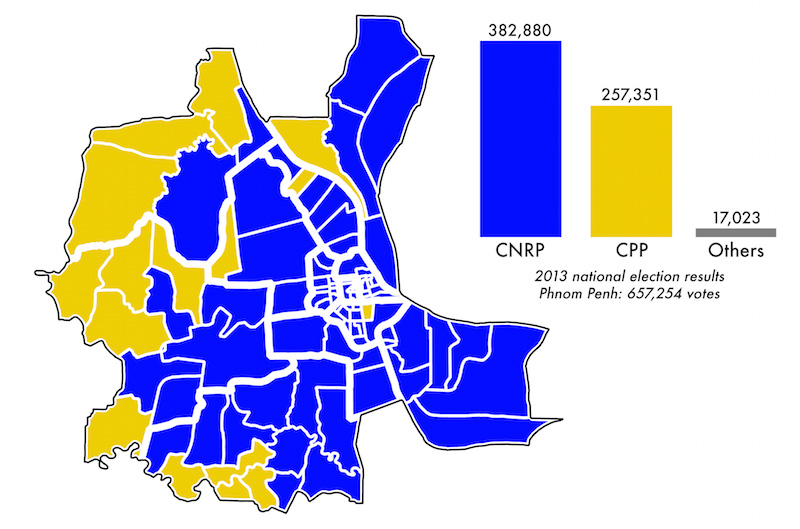

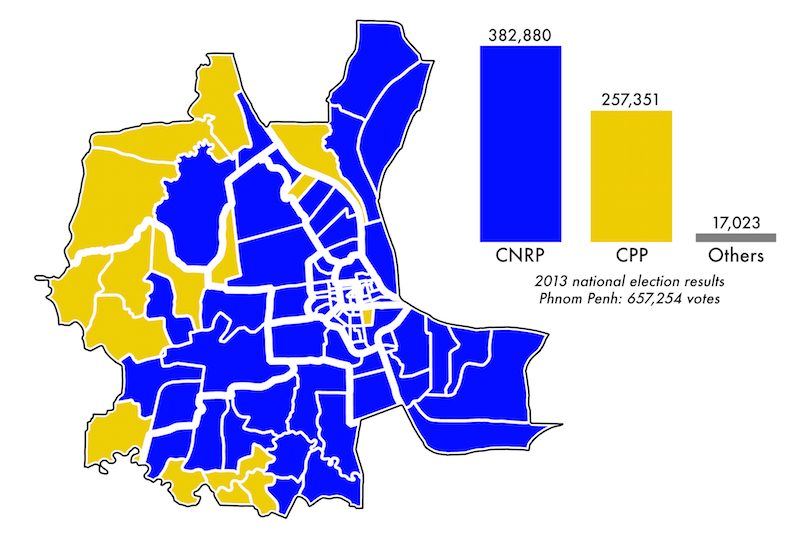

While that may be true, the CNRP enjoys broad support across the city and dominated at the ballot box in the 2013 national election before bringing tens of thousands of residents to the streets in the ensuing months.

For elected politicians, the disconnect could be problematic. But for Mr. Socheatvong, public opinion does not appear to be part of the calculation when deciding how to run the city.

Appointed by the ruling CPP, the governor stubbornly defends the ruling party’s interests even though the capital’s residents comprise the CNRP’s most reliable base of support.

“These crackdowns are…all about creating a culture of fear and intimidation which silences complaints in society against the government, and allows City Hall to then dutifully report up the ranks in the CPP that all is well in Phnom Penh,” said Phil Robertson, Human Rights Watch’s deputy Asia director.

Last week’s attack on land rights protesters, during which guards beat rights group Licadho’s monitoring manager Am Sam Ath, was just the latest example of Mr. Socheatvong suppressing any opposition to the ruling party, Mr. Robertson said in an email.

“Of course, the alternative is too hard to contemplate, since this would mean the CPP would have to recognize that their corrupt policies and practices are actually harmful and violate rights of both rural and urban people alike,” he said.

Koul Panha, executive director of the Committee for Free and Fair Elections, said the situation reflected a democratic contradiction in Phnom Penh: Mr. Socheatvong and the CPP control all the levers of power without popular support.

More than 80 percent of Phnom Penh communes voted for the opposition CNRP during national elections in 2013. The CPP won just 16 of 96 communes and 39 percent of the city’s total votes.

“Many people demand to have a regulation that they can elect a governor in Phnom Penh,” Mr. Panha said. “It’s not accountable to the people,” who “are unhappy with these kinds of restrictions—crackdowns and repression.”

In all provinces, governors are by law appointed by the ruling party. These governors—almost always ruling party stalwarts—wield sweeping powers over civic administration as well as security forces, including chairing “unified command committees” that oversee the local army, police, military police and public order para-police.

Naly Pilorge, deputy director of advocacy at Licadho, said governors should reflect the will of the people they serve, rather than that of the ruling party.

“No one would truly believe that current governors, virtually all of whom are members of the ruling party’s central committee, are acting and governing in a nonpartisan fashion,” Ms. Pilorge said.

“When it comes to ordering and enforcing restrictions on peaceful public assembly and expression, it is abundantly clear that their decisions are in no way based on upholding the public interest.”

Though there have been compromises reached by political parties over governorships before—after the 1993 and 1998 elections, power-sharing deals between the CPP and Funcinpec led to the two parties splitting provincial governorships—opposition leader Sam Rainsy said the possibility was not even worth discussing after the 2013 election.

Such a deal could not be struck under the current “one-party or communist-style regime,” he said. Calling the system of governorships “very anti-democratic,” Mr. Rainsy said Cambodia needed to move toward decentralizing power, and that “after 2018 the CNRP will implement a real and effective decentralization.”

If the party comes to power, Mr. Rainsy said, governors would no longer be political appointees. Instead, a CNRP government would draft new laws that give more power and financial means to democratically elected provincial or municipal assemblies.

Mr. Socheatvong could not be reached for comment over the past week. Mean Chanyada, a City Hall spokesman, said anyone suggesting that city governance should be more democratic needed a lesson in the law.

“Please: You, CNRP supporters and NGOs—go study the law again,” Mr. Chanyada said. “The governors of provinces and municipalities fall under the mandate of the Interior Ministry, which appoints them. There is no quota based on parties.”

City Hall does not restrict people’s civic freedoms, he added, though citizens wishing to partake in public protests must respect laws meant to protect the security and safety of the people in Phnom Penh. “The opposition party may want the Phnom Penh governorship, but, please, the opposition party shouldn’t be dreaming about that.”

(Additional reporting by Khy Sovuthy)