The ancient Silk Road sprawled across tens of thousands of kilometers, reaching east to west from Japan to Venice and passing through five seas. Together, the road and maritime trade routes linked more than 40 countries throughout Asia, Europe and Africa, fostering early globalization.

“They are the arteries and veins that carried goods, ideas, travellers and even disease for thousands of years,” said Peter Frankopan, a historian at Oxford University and the author of “The Silk Roads: A New History of the World.”

“It is important to think of them as plural and multiple,” he added in an email. “There was no single ‘road,’ and despite what many people think, the exchanges were not between China and the Mediterranean: The Silk Roads were—and are—like a web, criss-crossing and connecting cities, peoples and countries.”

Relations between China and Cambodia first developed through this network, said Rethy Chhem, a scholar and executive director of the Cambodia Development Research Institute (CDRI).

“Cambodia and China relations [go back] at least 2,000 years,” Mr. Chhem said in an interview. “People seem to forget that [through] the Maritime Silk Road in the 6th century…they shipped from China—from South China—and stopped here, stopped at the port somewhere on the seaside.”

In 2013, China proposed a modern revival of these international connections, which it dubbed the “One Belt, One Road” initiative. In response, academics and researchers from Cambodia—including a team at CDRI and the new Maritime Silk Road Research Center of Cambodia at the Royal University of Phnom Penh—have begun researching ways the country can position itself within the network.

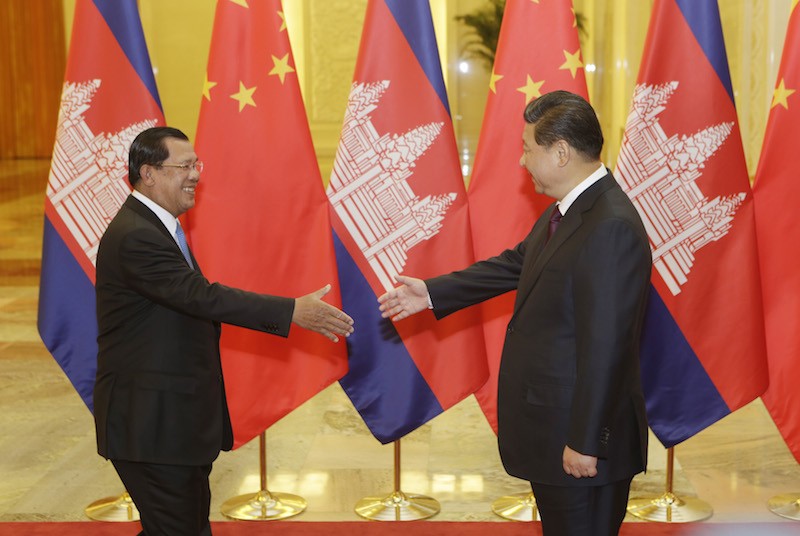

“China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ proposal is President Xi Jinping’s signature initiative,” Carl Thayer, a Southeast Asia expert at the Australian Defense Force Academy in Canberra, said in an email. “It aims to promote China’s prominence globally and in the process restructure the international financial architecture away from US and Japanese domination.”

While Cambodia had close relations with China before the initiative—Beijing has been the country’s biggest external lender since 2010—the plan provides an opportunity for Cambodia to engage in an economic network that covers half the globe.

“Cambodia will benefit indirectly through the improved connections that will happen when the very ambitious Silk Roads initiative is completed,” said Jayant Menon, the lead economist at the Asian Development Bank’s regional integration office.

“As long as the connections through the existing corridors remain, it opens up a broader network,” specifically for exports, he said.

According to Council of Ministers spokesman Phay Siphan, Cambodia’s recent efforts to integrate with the Asean Economic Community provided lessons that will be beneficial in pursuing opportunities in the Silk Roads network.

“Right now there are a number of economic networks—old ones—so the government is looking for another network. ‘One Belt’ can help…expand [the economy] from the country to the region—like Asean—and then to the Pacific.”

As the government pursues new growth, however, it must be mindful of negative repercussions and diligent about pursuing evidence-based policymaking, said Neak Chandarith, director of the Royal University’s new think tank.

“In Cambodia, most of the policies regarding any projects are not well-informed,” he said, adding that the think tank wants to provide information “so those bureaucrats can design and implement projects based on good, sound development for Cambodia.”

One concern is the impact of continued growth and accompanying development projects on impoverished communities, said Mr. Chhem of CDRI.

“Rapid development in any country carries some risk for the environment and for the community, and we have seen that,” he said.

“Another risk is that Cambodia along with Southeast Asia will be drawn into China’s economic orbit and come under increased political pressure to toe China’s general foreign policy line or at least moot criticism of China’s policies,” said Mr. Thayer of the Australian Defense Force Academy.

Indeed, Phnom Penh is already perceived as often acting in Beijing’s interests in both its domestic and international affairs.

Last week, the government was accused of scuttling an Asean statement expressing concern at China’s buildup in the South China Sea. The government also dismissed recent requests from Taiwan to have suspects in an telecom scam from the island be repatriated, instead sending them to China at the request of Beijing.

Critics and some in the political opposition have long warned that Cambodia’s rapidly increasing debt to China is unsustainable and that Chinese-funded projects—

often carried out by Chinese state companies—are done with little oversight or long-term thinking.

Mr. Siphan said the government did not bend to the will of any foreign country.

“We’re close with everyone, not just with China,” he said. “We’re close to China, close to the United States. We’re close to the E.U. We’re close to everyone.”

Mr. Chhem also said that alarm over China’s influence at this point was rash.

“Any small country needs to balance their international relations… to survive,” he said.

“China is not the first country to be assertive,” he said, adding that the U.S. was far more aggressive—and destructive—in its dealings with Cambodia in the 1960s and ’70s. “Let’s give China a chance to move through that—it’s too early to pass a judgment.”